My Igbo magical years: A short story (4)

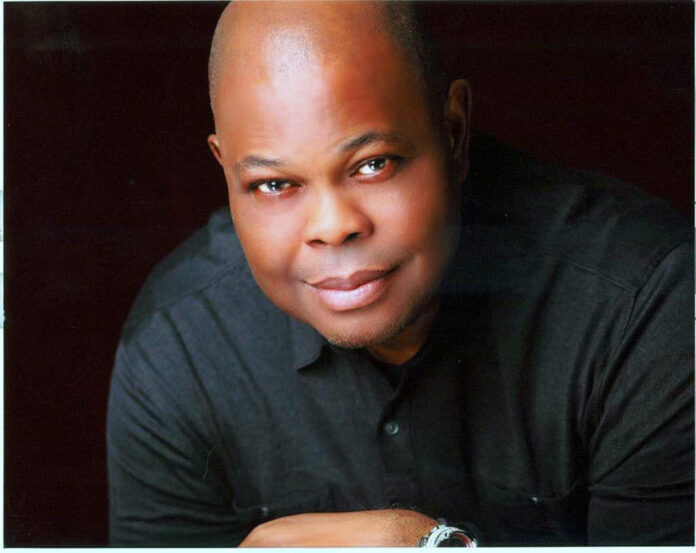

By Okey Anueyiagu

My father Chukwuma had deliberately initiated me into the world of Ndi Igbo. Being an early-riser to the values of being an Igbo man and a pan-Africanist in his days working with Nnamdi Azikiwe, the former President of Nigeria, as editor-in-chief of many of their revolutionary newspapers, my father entrenched in me those values that ensured my understanding of what it meant to be Igbo and a black person.

Chukwuma, my father began his journey into self-negritude by discarding his English name, Charles, and ensuring that all his children bore only significant Igbo names. He pursued and was one of those who championed the idea of a shared identity among Africans across the world. My father made me aware of my Igboness and at the same time, without ambivalence, the meaning of being black.

He urged me to never see my tribe or colour as a category to transcend, or a limitation to overcome, but as a deep inspiration to constantly make a conscious and passionate effort to affirm my Igboness and blackness with pride.

Today, as I write these short stories about our people and their traditions and cultures, I reflect on the lessons of my father and the sermons of my mother. I feel confident that I may have learnt a thing or two, and that my thoughts and feelings deeply represent a pilgrimage to the soil of my father and his ancestors.

When I write these wonderful stories from our ancient Igbo tradition and culture, I become thrilled to tell these tales that are loaded with intrigue and steeped in mysterious moral languages and lessons. Growing up, I was mesmerized by these stories and their deep intrinsic importance to our existence. And I believe that I owe the world a duty to use my little gift of being a storytelling writer, as I sometimes think of myself, to reminiscence about these events. I am very delighted that I have followed, even if in any small measure, in the footsteps of the griots, writers, and orators who have played indispensable roles, rediscovering, molding, retelling and transmitting the Igbo story. This has, no doubt deepened our understanding and appreciation of the complexity and the significance of the Igbo tradition.

READ ALSO: My Igbo magical years: A prelude

My Igbo magical years: A short story (1)

My Igbo magical years: A short story (2)

My Igbo magical years: A short story (3)

The story continues

As the appointed time for the village meeting began to approach, I started hearing sounds of people chattering from Ezi Nkweanya, the village square which was directly opposite my grandmother’s gate. My grandmother took time to dress up Nkoli in a nice simple abada up-and-down dress with a matching damask headscarf.

Nkoli whose parents came visiting earlier, was now looking radiant and glowing under the native powder and otanjele makeup that my grandmother carefully applied to her beautiful face.

Moments ago, Nkoli’s parents came looking for their thieving daughter who had taken refuge at my grandmother’s home. Her mother, Mgbeke looking disheveled and frowzled all over, upon seeing her daughter, fell on the ground and began to roll in the dirt, wailing about the shame that Nkoli brought upon their family. While Mgbeke cried uncontrollably, her husband Nwoshi stood by speechless, just swinging his fat shapeless head from side to side.

Hear Mgbeke: “Nkoli, kedu ife anyi melu gi – igbu go anyi, ifele ejugo anyi iru” – Nkoli, what have we done to you – you have killed us, shame has filled our faces. Her voice kept rising above with each word she cried out. With his hands clasped around his undulated head, Nwoshi joined in the admonition of their daughter, castigating and blaming her for the misfortune that awaited their family.

My grandmother jumped in and began to berate Nkoli’s parents. In an uncharacteristic manner, she raised her voice to a decibel that I had never heard from her. She began with Mgbeke: “kpuchie onu ule gi, anu ofia – akwunakwuna dika gi na ekwu okwu” – shut your smelly mouth, bush meat from the forest – a prostitute like you is talking”. My grandmother had lost it and she proceeded to remind Nkoli’s mother of her wayward behavior. “Umu nwoke none dinegolu gi – ina ibugheli ike na uno, na uno, kpuchie onu gi” – How many men have slept with you in this village, you are swinging your big bottom from one home to the other, shut your mouth up”.

And then to Nwoshi, Nkoli’s father my grandmother turned. “Nekwa nu onye ori nkea … Amudo akwugbulu gi mgbe ije zuo anu mgbada na nkpakala mmadu?” – Look at this one that is a thief … Did the Amudo people hang you when you stole another man’s antelope from his trap?”. Nkoli’s parents looking downcast, were ordered out by my grandmother. As they left, my grandmother kept raining abuses at them, holding her palms to her mouth made into an O shape, and letting out a loud yelp that sounded like a booming bullhorn. That shaming sound followed Mgbeke and Nwoshi as they exited through my grandmother’s huge beautiful gate.

My grandmother had dressed up in a regal attire of shining dress made of colourful damask, george, akwete and general wax print – all combined with an ichafu on her head. She adorned her neck and ankles with coral beads, and wore a pair of leather crosswind sandals that my mother had gifted her. She picked up her cane, and headed to the village square. Nkoli, the two servants and I, followed in tow.

At the village square which was beginning to fill up, the men and women sat apart. Underneath the huge and strong udala trees sat the village head and his supporting elders. I took a seat way behind the front row trying to conceal my presence the best that I could.

The meeting was declared open with prayers. First prayer was offered by the local catechist Mr. Abel who said a very simple prayer asking God in the name of Jesus to abide with the deliberations of the day. The next prayers was offered by Nwimo the chief priest of the Ofufe shrine. His prayer was more elaborate and carried very strong incantations and recitals. Nwimo who was an ardent heathen, like most other Igbo believers, followed the Igbo cosmological belief in the absolute existence of a Supreme Being, adopting an approach of accessibility to the various gods through personal or collective mediation.

The Amudo chief priest invoking his personal access to his supreme creator, began to pray to the village gathering. His long prayer in which he admonished the enemies of our village and praised the gods for that year’s bountiful harvests received applause with loud ise, ise, ise – amen, rending the air. I did not respond to his prayers, and the man sitting next to me nudged at me and reprimanded me. This man, through his toothless mouth wondered why I was mute at the end of Nwimo’s prayers, but offered a loud amen to the Christian prayers. He said: “Do you think that your white god is more powerful than our gods? That white god you worship,” he continued, “with his empty promises is powerless, and cannot save you today”.

As I was hiding somewhere in the back row, so also was Nkoli hiding behind my grandmother with her head and face covered almost completely with a headscarf called ichafu in Igbo. The meeting proceeded with the village head greeting the gathering and demanding decorum at the meeting. As soon as he was done, a village villain and a sworn enemy of my family who was my father’s cousin, without an invitation to speak, jumped up, and seized the stage. He began to shout out my name demanding that I got up from my hiding place in the back to the front row, where as he claimed, everyone can see my murderous face. I got up and was ushered to a seat in front. This man, an enemy of the family whose name was Mmuo came and stood in front of me. He began to wag his short stumpy fingers right in my face, almost poking me in the eyes. He came as close as a few inches to my face, from where I could smell the acrid irritating stench oozing out of his smelly mouth. They were smells of alcohol, native tobacco, and rotten decayed teeth.

I took this assault with quietude. Mmuo was not done. He bent down to the ground and took a position of a goat about to be slaughtered. He began to scream, asking me where I kept my long knives and offering his neck for my sharp blades. There was a complete uproar with many applauding his theatrics and excessive dramatic performance. At that point, the village head called him to order, and asked him back to his seat. He grudgingly returned to his seat, fuming and still pointing at me, insulting and mocking me.

They called up the first case of the day, and it was not mine – it was a more serious matter than the Nkoli and Okechukwu issue. It was a matter that drained my entire being and has remained etched in my inner self forever.

Upon learning about what this first case was all about, I was riveted and completely gutted by the unbending stringency of the matter. The narration of this case struck me as an invocation that challenged the legitimacy of the conventional laws and the legal system, and embraced native and traditional ways of settling and determining cases. This instantly suggested some sort of vexation and cynicism in the duel between constituted authority and native powers. This case for me as a young boy, opened a world of opportunity for exploring and questioning our traditions as it clashed with western civilization. It opened a treasure trove of discovery for me growing up.

In the packed village square, the case between the People of The Amudo Village and Chief Chukwurah was called. During the Christmas festivities that just passed two female worshippers lost their lives on the prayer ground in Chief Chukwurah’s compound. Chief Chukwurah, a very wealthy indigene lived in a faraway township, and without fail, returned to Awka to celebrate every Christmas. He was a very kind man and a staunch Christian. He had built a magnificent mansion that had a large expanse of land in the frontage. His house served as a suitable space for hosting and entertaining a very large number of people. On every Christmas eve, he hosted many parties. He would slaughter cows, goats and chickens and cook lavish meals.

Musical groups of both traditional and church denominations, played at his functions. The previous Christmas, tragedy struck at Chief Chukwurah’s party. Chief Chukwurah who was a very tall and huge man, was also an extremely handsome fellow. He stood shoulder-high taller than most men from the village. He was a gregarious man whose smile and laughter disarmed everyone. He was stupendously loved and respected not only in the village, but beyond. His generosity endeared him to the entire town. The tales about his philanthropy and his willingness to lend a hand to the poor and needy became legendary.

As Chief Chukwurah returned home for this Christmas’ celebration, he was oblivious of the tragedy that awaited his arrival. He drove into town with his family in his gleaming black Mercedes Benz car, and another pickup loaded with goodies for the villagers in tow. Everyone looked forward to Chief Chukwurah’s homecoming, as he had become the toast of the town.

During the midnight celebrations at Chief Chukwurah’s compound, a Christian musical group in a carol proceeding and outing had entered the premises singing melodious choruses and playing drums, tambourine, and trumpets. After eating and drinking to fullness, the Christmas carol troop gathered underneath Chief Chukwurah’s two-storied building. He stood on the deck overlooking the Christmas revelers while acknowledging their salutes and praises. As was a regular tradition of Chief Chukwurah, he pulled out his double barreled winchester rifle and began to fire rounds of ammunition in the air. With the pop of each round, the crowd responded with thunderous applause. Smiles of joy and satisfaction broke across his face as crisp smell of gun powder rent the air.

Then, the celebratory gunshows turned to an eternal nightmare when Chief Chukwurah’s gun rounds accidentally hit two members of the Church choir in the procession. They died instantly, and there was a general stampede. An abomination had occurred and Chief Chukwurah was in very deep trouble.

The midnight tragedy had slowly closed in on Chief Chukwurah. His entire life had just been truncated. From the top balcony, he lowered his eyes like an exhausted fighter to behold the bloodied carnage beneath the foliage of the two dead bodies.

He closed his eyes hoping that he was dreaming. When he opened his eyes, the scene of murder remained a reality, and his misty, dilated pupils became transformed into a thoroughly sapped countenance.

The entire village was thrown into mourning. The villagers moved rapidly to contain the situation. There was no police report. Because Chief Chukwurah was so beloved, the unanimity of silence was upmost. Instead, the village chose to sit in judgment of this matter. A quick and private burial was conducted for the dead, and a date set for the hearing and judgment on the matter.

The judgement day had just arrived at the Ezi Nkweanya village square, and the darling of the town had suddenly become the villain. His case must be tried and judged according to the native laws and customs.

The huge man dressed in an all-black long robe, and a long red cap that carried two feathers of a very rare bird called ugo – a bird that has sacred status within the Igbo. The feathers of these rare birds are affixed to the caps of well-respected titled men as symbols of honour and authority. His case was called up by the designated village orator, a man of great garb. He announced the matter in a rather whimsical manner, carrying on as if he was the executioner. He began by telling the gathering the parable of the hangman, his noose and a fat man’s neck. The gathering stayed silent as the orator while narrating the details of the incident, veered off several times with stories of unrelated matters obviously attempting to impress the gathering with his oratorial skills.

As Chief Chukwurah stood in the center of the village square many men took turns to speak mostly in his praise and adulation. Then came his turn to speak, to offer his defence. He began in a soft and tender voice to thank God and His son Jesus Christ for the genuine bonds of fraternity in the village. He began a Church Chorus and most of the women joined and almost brought the house down. I whispered mischievously to the toothless heathen sitting by my side: “Do you see the power of Jesus, don’t you hear it in the sweet voices of our beautiful women?” He hissed, looked away, ignoring me.

Chief Chukwurah’s voice rose and he began to tremble as he spoke. His voice was filled with sadness and regret for what he did. The man who had for many years shared unshakable love with his people, especially the poor and the needy, and filled many hearts with joy, now stood alone and fighting for his life in the village square. As he delivered his speech which was not necessarily a defence, but a supplication to God, he kept staring at the sky which at that moment held no hope nor meaning for him. His heart that used to be filled with confidence and courage, now held no value and carried nothing but the weight of despondency. The truth that was before him was cold and merciless.

Chief Chukwurah continued to speak, this time looking directly at the village head and the elders. “The truth is heavier than fame and fortune.” He said: “I have failed you, and I have let my God down.” He paused, his eyes glittering under the fading sun. “I took the lives of two innocent souls… I am guilty. I am a man wrestling not with any disease, but with the fate of a fainting fame and a haunting echo of despair… This life is meaningless and I deserved to have died a worse death than that which I brought upon those innocent girls”. He stopped for a moment, and began to sob. Many of the women started to cry, some wailing.

He continued: “Today, as I watch the sun melt into the horizon, so also do I watch my life melt into the pits of hell … I am a finished man, and I beg for God’s forgiveness and for you my brothers and sisters, my umunna, to find a place in your loving hearts to forgive me, and accept my apologies for the grave sins, the alu that I have committed.”

With this he bowed, walked to his seat as the gathering exploded with cheers, applause and wailings. I could have sworn that even a few of the men were caught wiping away tears.

Most Amudo village meetings at that time would have been inconclusive without an input from Uncle Nwoye. Nwoye who was considered to be an “intellectualdrunk” must speak, and he spoke only in the English language – and it didn’t matter to him that the majority of the villagers did not understand a word he spoke, but in the English language, he must speak. Surprisingly, the village illiterates were the ones who applauded Nwoye the most with every thunderous word he dropped.

Nwoye the very brilliant son of Nweke, had spent about ten years at Cambridge University in Britain, pursuing a degree in Classics and Literature, but had returned empty – handed without a degree to the consternation of his distraught father.

Nweke had spent his entire life’s savings earned from working as a road-maintenance engineer with the PWD, sending his first son to England. Nwoye returned with nothing but a pipe for tobacco smoking, a musical flute, a guitar, a drunken head, and purely unadulterated Queen’s English accent. He rarely spoke to anyone in the lgbo language, and when he did, it was laddened with an English slant and perforations.

It was rumoured that when Nwoye arrived England for studies in the late 1940s he got tangled with a bunch of English royalties who didn’t care much about studying, but were more induced by the life of partying, drunkenness and womanizing.

Nwoye fitted in properly as he was a very handsome, strong and well-mannered African student. He began to play in the university rugby and hockey teams, and instantly became a star on campus. His stardom got to his head, and he began to pay less attention to his studies, and instead dilly dallied into alcohol and women.

As the white women loved Nwoye, so did the alcohol seize his life. He derailed and never was able to finish school. His father was heartbroken.

Nwoye returned to live in his father’s mansion in Amudo village without a job. He played his flute and guitar at the village square under the moonlight at nights entertaining villagers who found his lifestyle fascinating. He never married but may have fathered as many as ten children with several women who had fallen for his charm. He was the village gigolo often living off widows and desperate women.

Nwoye dressed in a typical English gentleman’s style that stressed timelessness and impeccable fit of a garment made of grey tweed suit with a waistcoat of similar form, a polished black shoes, a trilby hat, and a black bowtie effortlessly knotted with a careful curation on a light blue wingtipped shirt. Nwoye looked stunning, but in the midst of the locals, was very inappropriately attired. Clutching his tobacco pipe, and a full flask of liquor neatly tucked in his breast pocket, Nwoye didn’t care, and was ready to exercise his rights in the defence of Chief Chukwurah who since he returned from England, had been one of his main benefactors.

As soon as Nwoye took his position to speak, the villagers in anticipation, rose up in thunderous shouts of excitement and joyful rancour. His father who sat quietly in the back, rose up, with tears in his eyes, left the village square and began a return to his home. Nwoye began to address the villagers in his Queen’s English with a full display of elongated vowels with distinctive sounds and pronunciations reserved only for the English royalties and the upper-class. This was happening in the Amudo village square in Awka.

Nwoye a master of the Shakespearean English speaking style, began with famous Shakespeare quotes: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” “When we are born we cry that we are come – to this great stage of fools … the web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together … you cannot, sir, take from me anything that I will not more willingly part withal-except my life, except my life, except my life.” Nwoye looked up to the sky, and then returned his gaze to the stunned villagers, who mostly didn’t understand a word he had spoken, and sensing their general sense of amusement, released his last Shakespearean quote, this time choosing from HENRY IV PART I, ACT 5 SCENE 2: “The time of life is short … To spend that shortness basely were too long.”

Nwoye broke from his quotes, dipped his right hand in his inner breast pocket and whisked out a silver-coloured flask, twisted the cork open and took a long gulp of substance I reckoned was a local brew of gin known as a eshilieshi. He took a deliberate belch that echoed off the silence of the observant crowd, while stocking back his alcohol pouch in his chest pocket. From his outer breast pocket stuck out his tobacco pipe made of glittering wooden ensemble. He lifted it, and lit it up blowing a wild smoke. The smell of the aromatic erinmore brand of tobacco filled the air. It was a very sweet scented smell that I liked so very much – it made me want to smoke so badly.

The smart Englishman from Awka had captured the attention of the constellated cluster of the Amudo village gathering with his wit and loaded grammar. He strolled nonchalantly like a monarch to the stand where the village head and the elders sat, bowed and tipped his hat, adjusted his bowtie and began to speak in a sonorous and imposing, deep and confident voice. He was not in any hurry with his speech as he picked and chose his words very carefully, giving them very weighty tones and harmonious resonance.

Using an old and archaic English phrase used in speeches to attract public attention, Nwoye began to speak in defence of his friend, Chukwurah: “Hear ye, hear ye, I have come before you my brethren not to inveigh, or to protest with great anger and hostility about the possibility of any sanctions against our brother, because if we take any drastic decisions against him, it would harm our community… when we misstep we must deploy tolerance, inclusivity and understanding amongst ourselves and eschew bitterness, hostility or hatred towards one another. I do not desire to disport or frolic about this serious matter, neither do I wish to hornswoggle you unnecessarily.”

Nwoye turned to the rest of the gathering, raising his voice, he continued: “This imbroglio must end… what this complicated situation will serve our people is nothing but intricate conflict leading to a state of confusion and uncertainty that will convolute and perplex our already tangled customs.”

As Nwoye spoke, he kept acknowledging positive nods coming mostly from the village Illiterates who didn’t understand a word he spoke, with reassuring smiles signifying that more high-sounding words were on their way. Sensing a kill, Nwoye’s magniloquence rose, and the villagers responded with loud gasps and shouts with every big words he spoke.

Then the time for Nwoye to lower his boom came: “This anomaly is a calamity with copacetic macabre and demure… we must never abdicate our capricious and evocative duties and extrapolate on frivolous juxtapositions of loquacious inanities… wake up my people, and let us abandon this antiquated and apoplectic bombastic capacious idiocy.” The arena was on fire. He took a deep breath and continued. “This oxymoronic exhilarations and cacophonies must stop… are we going forward, or embellishing the dark ages of our past? He asked with a cynical twist to his now agitated voice. The villagers stood on their feet cheering every big words he released. Nwoye glanced around them, and bowed, tipping his hat and smiling widely. He then took another drink of his strange brew and shook his head in a sign that showed appreciation of his performance, and of the crowd’s response.

The gathering began to chant loudly: “Supu oyibo, gboba inglis ka nli ewu” – blow the Whiteman’s grammar, vomit it like goat’s regurgitation. Nwoye raised his fists and bowed several times. He was now drunk and intoxicated by both the strong alcohol, and the crowd’s accolades. He could not stop now. “We must display equanimity in the face of this fiasco – where is our mental and emotional stability in this peat bog, slough, pocosin and complete disaster? …we must confluence, brainstorm and act with ambivalence to resolve this conundrum in efficacious and perspicacious ways… failure will be dangerously pernicious… pestiferous, deleterious, noxious, inimical to us all.” He rounded off his tutorial in big grammar to the villagers, and staggered back to his seat to a standing ovation.

Basking in the euphoria of his strong manifesto to the villagers, Nwoye did not anticipate the tragedy that awaited his return home. His father Mr. Nweke as he was walking away from his son’s theatrics, clutching his walking stick and gingerly walking home, looked back a few times at the villagers cheering his wayward son on, wiped away tears, and began sobbing quietly. He returned home, laid out on his bed, took his last breath and died. Nweke died with sadness and sorrow in his heart. He could not phantom that he had produced a child who had become a village clown and jester. He wandered why his gods punished him with such a misfortune in a wayward, itinerant and irresponsible son. He had to lay his weary head to rest hoping to find peace when he was gone.

The early morning wailings heralded the announcement of Mr. Nweke’s death. His long body was laid naked except for a flowery loin cloth that covered his lower body. His long big nose stood out on his bald and very dark head. His body laid stiff and was surrounded by close relatives. The wide contour of his naked chest stood out strong, and in the temple of his chest, was placed an extraordinarily large egg of a vulture. This egg, it was explained, was an old Awka traditional way of assuaging the anger of the dead. This was to ensure that they didn’t come back to haunt the living.

As the villagers gathered and were preparing the grave site, singing and performing native rites, Nweke’s son Nwoye sat in a corner in his father’s compound, dressed in a black long-tail English suit and armed with a harmonica and a beagle in his hands. He took turns playing both instruments with melodious old English funeral rhymes. Intermittently, he would stop to wipe away tears from his eyes, while allowing the village musicians to play their uli and ekwe solos of beautiful traditional Awka renditions. If those Nwoye’s tears were tears of regrets and contrition for his shameful treatment of his father, and were remorseful and penitent enough, it was difficult to ascertain. But what was certain, was that Nwoye’s heart was heavy with something, at the very least.

Perhaps, Nwoye’s tears at his father’s funeral came from his remembrance of his long-lost wasted years in England which his old-English tunes brought back with melancholic sadness.

Engrossed in the joyous effusions and sincerity that followed Chief Chukwurah’s perfect delivery, and other activities, I almost forgot my impending problem. As my name was called to appear before the village gathering, I jumped off my seat in half-panic. I carefully began to rehearse all that I had memorized and stored in my brain for my Amudo brethren. Suddenly overcome with fear, excitement and anxiety, I greeted the gathering in an unadulterated Awka dialect. “Amudo kwenu, muo nu, kacha nu…” – Amudo cheer up, procreate, and be the greatest. I received very scattered response. I began my defence after the village orator laid-out my case, and like a prosecutor, a jury or a judge that he wasn’t, concluded that my actions deserved very severe punishment.

I cleared my throat and began to pace up and down the square and directly before the elders without uttering a word. Being a fan of old Court TV shows like “Perry Mason Show, Judgment at Nuremberg” and others, I had acquired the mannerism of those lawyers in the courtrooms. I intended to use these tactics to create some illusions about me and my case. Whether I succeeded or not with my antics can be a subject of personal conviction. But I surely captured the attention of the gathering as there was absolute silence as they eagerly waited to hear what I had to say. And I had a lot to say.

I began my defence with what I now, with the benefit of hindsight consider to be arrant impudence. I did not apologize. There was a loud gasp in the gathering when I accused the villagers of practicing archaic and unlawful tradition – practices that were against the laws of the land and the laws of God. It took several minutes to quell the uproar that followed my outburst. I stood my ground and continued to point out to the now very agitated crowd that there were no basis in law and in religion that permitted the treatment they meted to Nkoli.

Sensing that I may have provoked the villagers enough, I switched to my planned strategic defence. I was going to invoke Christian teachings from the Bible to strengthen my points. My plan was to instill and instigate Christian sentiments into the matter, win the sympathy of the Christians, and use their support to divide the villagers.

When I was very young, my father instilled in me the habit of reading, and I became proficient in this. My mother cashed in and gifted me with a huge Bible that had a lot of interesting illustrations. I read this Bible like a novel and enjoyed the stories from the holy book. By the time I was six years old, I had read most of the Bible.

Before appearing at the village square hearing, I locked myself in my room, and began to read this Bible again, searching for portions that dealt with sins, mercy and forgiveness. I found many.

I raised my voice above the rancor of the still angry gathering. I began: “My elders please hear me. Have we forgotten what Jesus told us in Luke 6:36 – To be merciful just as our Father is merciful – to embody the mercy that characterizes God?” I instantly had arrested the attention of the Christians. I continued, and this time referring to Exodus 34:6-7: “The Lord, the Lord, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin.” I went to Lamentation 3:32: “Though he brings grief, he will show compassion, so great is his unfailing love.”

I continued to quote verses in the Bible that demanded that we showed mercy and forgiveness in the same way that God is always willing to forgive sinners. Matthew 5:7: “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.” I began to emphasize that it is only God that reserves the right to punish us and has the prerogatives of mercy and of forgiveness, and that we must all have compassion and tread our sins underfoot and discard our iniquities away. I invoked the indescribable, unmerited mercy and forgiveness that we all receive from God, and how we must strive to, in turn, forgive our brothers, sisters, fathers and mothers, friends and enemies, in line with the spiritual truth of God.

The gathering was stunned. The Christians were cheering, and the heathens were shifting uncomfortably in their seats. I had divided the villagers and was now going for the jugular. I looked in the direction where two twin brothers Peter and Paul sat, and began to talk about the old custom of the killing of twins. I reminded them that Peter and Paul would not have been here if the Whiteman did not forcefully abolish this horrible culture of the killing of twins. I moved my glare in the direction of Nkoli and asked: “why are we still treading in our old archaic ways by parading our daughters naked to the world… why are we still stuck in our abominable ways, disgracing our children, and ignoring the admonitions of God to forgive and show mercy and love?” I asked again: “Are we not all children of God?” A resounding “yes” followed. “Must we continue to act like people without the fear of God; unforgiving, wicked with sinful minds?” “Mba” rented the air from mostly the Christians.

“Please listen to what I’m telling you!” I exclaimed. “We must never treat our own like we treat animals.” I began to raise my voice. “Can’t we see that we have descended lower than the animals we breed? We must bring back honour and respect to our lives. We must confront those traditions that set us back centuries, that terrify our civility and make us worse than barbarians. We must know and always do what is right.”

As I concluded my defence, I felt my shoulders drooping and my body sagging with some riddles of nervous spasms taking over my entire being. I also felt infinitesimal muscular twitches and contractions inside my entire body beginning from my head to my toes. I felt myself caught in the steely sights of the villagers. Then came a thunderous applause that followed me as I walked back to my seat. I caught a glance of my grandmother beaming with a wide smile that spread across her beautiful chubby face. Behind my grandmother, was a picture of relief on the face of Nkoli, who for the first time since her persecution was smiling. My grandmother rose from her seat, walked cautiously towards me, met me halfway, and held me tightly in her bossom. She had sent a strong signal to her supporters, who were many, that she stood with her grandson.

As I proudly took my seat, I began to think of what my parents would have thought of me and my performance before the villagers. Now in the weariness of all the problems that I had brought upon myself, I was so sure that they will feel proud of their son, and will be reassured that they have raised a determined and strong child. I carried this feeling for several years until I watched both of my parents die and dissolve into unbelievable silence whose emptiness lingers and has refused to leave me.

Once I was done, a few of the villagers were allowed to speak. Opinions were evenly divided with most of the speakers, while admitting that there were some values to my defence, agreed that I had no authority to disobey and threaten the traditions and culture of the land. Throughout this marathon of speeches, I maintained a blithesome disposition without betraying fear of the punishment that many prescribed and recommended to the elders to dish out to me.

The Otochalu and the elders rose from their seats, and retreated to the adjoining village obu for deliberation on all the matters. They returned after what seemed to me like eternity to deliver their verdict. They began with Chief Chukwurah. The village head gingerly rose to this feet and asked Chukwurah to take the stand again.

He began: “Onwu egbuo ka alulu aka… mbosi mmadi kwalu mmadi, ka okwalu onwe ya…” – Death has killed like it was appointed… the day one celebrates the death of another, is the day that person celebrates his or her own death…” He continued: “Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself – freedom is just not the ability to do the right thing, but also to make a deliberate choice to choose circumstances and to take responsibilities for your mistakes. When one missteps, it is not the doing of God, but our own instinct or some moral code or scheme of calculations” He looked directly at the Chief and said: “The way you made your bed, so shall you lay on it… we the people of our great village find you guilty of murder, and you must depart this village, and indeed, this town this night with your entire household, and must never return or set foot here in 7 years”. With that pronouncement, there was pandemonium everywhere. Many were wailing and rolling in the dirt.

Chief Chukwurah bowed his head with tears flowing, and left the gathering. He departed the village instantly and never returned. His home was empty and desolate, and became overgrown by bushes. He was heartbroken and never returned home again. He died in exile.

This episode was so crude and shocking that I remained seated on my seat, shaken with disbelief that such a powerful and beloved member of our village could receive such punishment. I became nothing but a weak little boy awaiting his sentencing. I thought at that point, that I was done.

It was my turn and the Otochalu without uttering a word, took one look at me, and I knew to quickly take a stand in front of him and the elders. With my two hands clasped behind my back and my head bowed, I closed my eyes and attentively listened to the Otochalu, the man I had enjoyed many stories with at our home in Kano, and with whom I had just very recently shared kola nuts and some gin.

He looked up at me and with a stern face began to address me and the other villagers. “If I am asked “what is good”, my answer is that good is good, and that is the end of the matter” Otochalu, the philosopher had spoken deeply and I was confused. “Doing the right thing is not always the same as doing what is right, and doing good might lead to pain and suffering to others… moral goodness is not always right…” I became more confused and unsure of where he was going. He turned around, and began to speak to the gathering. “Humanity represents the ocean, and if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean is not ruined. We must not lose faith in humanity… we must trust humanity to change our world for the better. We must lead by example and be the change we desire to see”.

With that the Otochalu turned to me and began to give their judgement. “Okechukwu our son, you have erred in your actions, but you’re still a child and learning the ropes of our culture and traditions. This village looks up to you with hope and expectations for a productive period in your life. We know that you will one day make us proud and bring fame and fortune home”. He now raised his voice so that all could hear him. “We therefore find you not guilty and discharge and acquit you of all the charges brought against you here today”.

The arena erupted. I walked to him, shook his hand firmly, and dashed to the warm embrace of my crying grandmother. Nkoli received a punishment to sweep the village square every day for six months.

- Okey Anueyiagu, a Professor of Political Economy is the author of: Biafra, The Horrors of War, The Story of A Child Soldier

Concluded