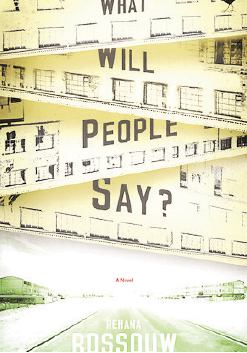

Book Title: What Will People Say

Author: Rehana Rossouw

Genre: Fiction

Pages: 332

Publisher: Jacana Media

Year of Publication: 2015

Reviewer: Adeniyi Taiwo Kunnu

The greater chunk of our world may be sailing on the winds of the seemingly unending political problems, the terrorist attacks, depletion of both crude and cash reserves, or better said, the generality of the bitterness which pervades our human space. These are realistic aspects of our troubled lives, but when a work concerns itself so much about human lives from the very root of it, which is the family, it becomes obvious that attention is being paid beyond words, although this is word-business.

What Will People Say splatters on each flip of the sheets obvious fictional account, but true to our daily activities and interactions in 332 pages and precisely 32 chapters. Rehana Roussow pitches the conflicts of the home deftly among one another and with the dexterity of a trained seamstress brings all issues to intertwine, as the loggerheads of ‘litluns’ and ‘biguns’ wriggle to the fore. Notably, the saying about ‘little leaven leavening the whole lump’ finds its place in the work of the South African.

The vicissitudes of life visit the Fouries and leave them differently, or rather impact them in ways that are permanently altered. Neville Fourie’s job as a messenger at a law firm enables some income for the family, when combined with Magda’s take home from the clothing factory. Both think their family is just well and without worries, until the aspiration of their teenage children spur them in different directions. Nicky, whom through this work is seen for the greater part, has aspirations to become a lawyer with the hope to leverage her intelligence.

Suzette, the elder to Nicky and the eldest of the Fouries’ three children, believes her way out of poverty is to become a model – having been nudged in that direction owing to the affirmation by her friends because of her good looks. She will stop at nothing to attain that and live her dreams. Anthony, who is only son and last of three for the Fouries, has penchant for power and money, but unknown to only a 13-year-old, the consequences of leading a life full of lies could lead to a painful end.

Rehana Rossouw engages the misnomer of parental guidance, when Mrs. Fourie allows her love for Anthony overshadow the careful attention she would have paid to her favourite child. Neville, on the other hand, feels contentment for meeting his children at home after work, but the activities that take place between after school and his return from work appear inconsequential but dire.

By implication, the author calls our attention to the lapse of not, as in a book, reading between the lines of the actions of our children. Be there and ahead of their ever-changing antics.

What people will say seems more important to the Fouries, especially Magda, the woman of the house, whose high-handedness allows Suzette cook up lies that work for her all the time she sleeps away from home, has sex at a church camp meeting, misses school for weeks to get a job before eventually dropping out, has a romp getting high on cocaine and at another time almost gets raped.

The lessons are replete for parents, guardians and every individual to learn, that the minds of adolescents differ completely from the teenage junctures of young lives.

The society also gets flayed for its part in Anthony’s demise. At 13, the first year in the teenage circles, not much is known no matter how much the teenager claims to know. Ougat, the one who lures him into dealing in drugs and his eventual deflowering when he rapes his elder sister’s friend, Shirley, is one of the many instances of gangs and gangsterism that the society needs pay attention to. Anthony crosses the Rubicon and gets killed in cold blood. His parents want just good grades from school and religiousity, but are handed a dead son.

Rossouw examines the underbellies of the South African society and in very practical ways, Africa and the rest of the world. She boldly speaks to the issue of the family, which ppears to be getting lesser attention these days. She obviously opens the reader’s heart to listen more, care more and watch one’s wards more. The days on many fronts are painfully evil, and without being vigilant, the loss to the family unit could be very difficult to heal. Her ability at free expression is delicious, even as she employs immense vocabulary of South African emanation, which includes Ouens, Kwaai, befokte, ghafees, among many others.

The historical juncture in which the book is set is also symbolic as much as symptomatic of the upheavals that run through the pages. The Fouries lose a son in Anthony, but his rape produces a son from Shirley; one of their daughters, Nicky, becomes a paralegal with jeopardy to her dreams of becoming a lawyer and eventually not marrying Kevin – her lover. The Church of Eternal Redemption that Magda holds in esteem and pays her tithes dutifully to throws her family out when it needs the church most. Her marriage also comes apart after her son’s death rips it to shreds, causing her husband to pitch his tent with a neighbour who already has five children from five men.

“People got a democratic right to fuck up their lives…. They got used to their oppression, they don’t know any other way. Your job is to show them a better life, but you can’t force them to accept it. You got to keep conscientising them, eventually they will get the message….” (page 307).

Life is a choice and must be lived consciously by making the right choice. These musings are no doubt the author’s.

• Kunnu is a Lagos-based literary scholar.