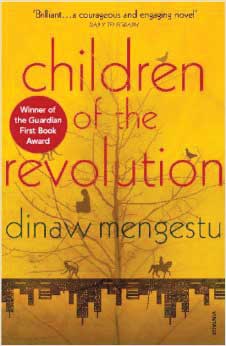

The book, Children of the Revolution, by Dinaw Mengestu, reviewed by Lindsay Barrett and published by Vintage Books, London, is the book-in-focus for February at the Port Harcourt World Book Capital (PHWBC) in Rivers State.

It is a challenging task to treat the experience of separation from one’s homeland in a delicate, not to say rational, manner in a tale about passionate emotional encounters in exile. But that is what Ethiopian author, Dinaw Mengestu, has achieved in his remarkably sensitive debut novel.

It is a challenging task to treat the experience of separation from one’s homeland in a delicate, not to say rational, manner in a tale about passionate emotional encounters in exile. But that is what Ethiopian author, Dinaw Mengestu, has achieved in his remarkably sensitive debut novel.

He has created a hesitant and somewhat reticent protagonist in Sepha Stephanos, a lowly Ethiopian shopkeeper exiled in the United States for nearly two decades. The spectre of his decidedly low self-esteem embodies the intense disenchantment of exiled Africans whose idealistic revolutionary dreams have been dashed by the reality of corruption and tyranny in their homelands.

Mengestu is, in fact, one of a trio of such disenchanted “children of the revolution”, the other two being his close friends, Kenneth from Kenya and Joseph from the Congo. Their importance and relevance to the heart of the tale is signalled right from the very first sentence, as it records their weekly visit to their friend’s barely viable emporium as a major event in the life of the lonely trio.

As the narrative progresses, however, they retreat into the shadows and become marginal but nonetheless vital symbols of the frustrating isolation that exile represents for sensitive and ambitious individuals.

As a result of the informal deterioration of interaction with his fellow exiles, Stephanos grows increasingly nostalgic for his family and his homeland. It is this mood that informs his encounter with a neighbour who moves into a dilapidated building and begins the work of rehabilitating it and also initiating with him a friendship that promises more but ends up providing less.

The neighbour, Judith, is an attractive young white female university lecturer with a precocious young daughter. The child, Naomi, a sensitive and curious 10-year-old, becomes a close friend of Stephanos, a friendship that she initiates and consolidates by asking him to read to her from story books that she selects from a library and brings to the store.

As this relationship grows, the mother signals her own desire to develop a more intimate relationship with Stephanos herself, but his natural reticence as well as his intrinsic shyness proves to be an obstacle rather than an asset. The encounter between himself and his neighbour therefore serves to reinforce the sense of separation and isolation that is the central core of the psychological dilemma the author addresses in the entire work.

An especially revelatory aspect of this work is encapsulated in observations about the neighbourhood in which Stephanos lives in Washington D.C. He defines the deteriorating condition of the inhabitants’ lives by describing physical conditions symbolised in the decay and then the tentative rehabilitation of the triumphal statue of an obscure General after whom Logan Circle, the enclave where his shop and his home is located, is named. This observation is used as a leitmotif for the social decay that has devastated the mainly African-American community in which he is both a member and an outsider.

The sense of memorial loss that he dredges up when recalling childhood experiences in Ethiopia becomes the crumbled foundation of a personality that cannot take root in the community, and which leaves him unable to relate with Judith in a rational and emotionally stable manner. As he gradually uncovers details of her background, the differences between them, rather than any possible points of concord that could encourage a harmonious relationship, become prominent. When she attempts to participate in a social protest generated by members of the community resisting the invasion of the area by upwardly mobile tenants like herself, she is roundly rejected and Stephanos is too uncertain of his status to come to her defence.

When Stephanos discovers that Judith was once married to an African don who is the father of her daughter, this fact only serves to reinforce his doubts about his own suitability as a suitor. He has grown increasingly doubtful of his own intellectual and social graces over the years, as his shop wasted away as a result of the national economic debility and a lack of interest on his part.

Judith goes on vacation and returns without Naomi who she has placed in a boarding school, and this signals the beginning of deeper separation between their lives. It is at this point that his friends, Ken and Joe, resurface as vital forces in the novel, though they remain marginal as active characters in the narrative. He regards their own gradual descent into a life of routine drudgery and loss of hope as symbolic of the abandonment of his dreams and the promise of a return to his homeland. This profound awakening to the reality of loss is the most credible expression of self-realisation in this work.

As he dredges up personal memories and traumatic reflections on the tyranny that took away his father’s freedom and then his life, during the regime of the “Communist Dergue” in Ethiopia, Stephanos realises that he has become the embodiment of a lost soul rather than the epitome of the revolutionary urge that many Africans in exile cling to as justification for their exile. This sense of disorientation is also stressed through an incident in which he visits the home of a distant relative of his who had been his tentative guardian when he first arrived the U.S. His “uncle” is not in, and as he snoops around the apartment, he realises that they no longer have anything in common, except their mutual disenchantment with the conditions that had existed in their homeland when they escaped.

Mengestu has a special talent for observing and describing the inner life of his characters while making it seem that he is simply narrating the ordinary processes of daily existence. The authority with which he deploys this facility is at the heart of the success of this simple tale of personal emotional frustration and gives it a resonance that belies its modest scale.

In the final analysis, his inability to accept exile as a genuine alternative to return is the most profound impression that emerges from his encounter with Judith who abandons the community soon after sending her daughter off into the educational wilderness. Naomi’s removal from his life and the loss of friendship that it entails is in fact the central loss that shapes Stephanos’ most profound reflections on the dilemma that confronts him after he realises that Judith’s effort to connect with him has eventually been abortive. Mengestu has placed this effectively delineated failure of personal initiative right at the heart of his tale as he sums up the experiences that the community in which he lives has encountered in the period of his narrative.

Judith becomes the focus of the community’s bitterness when a local mad man torches her house in act of random delinquency, which nonetheless symbolises the collective despair that the condition of exile represents for the central character.

In the end, Stephanos and his fellow exiles are seen to be the victims of a reality in their homelands that finds no relief in the metaphoric escape that exile supposedly represents.

The Rainbow Book Club choice of this remarkably sensitive work as a Book of the Month reinforces its tradition of seeking out works of the highest quality to provide their readers with an enlightening and particularly profound experience.

As usual, the reading will hold at Hotel Presidential, on Sunday, February 22, 2015, from 3pm. It will be followed by a drama performance.

• Barrett is a Jamaican poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, journalist and photographer who lives in Nigeria.