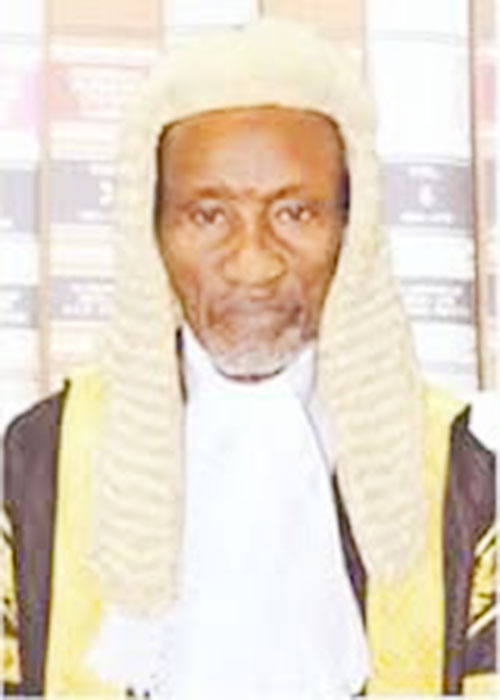

The decision of the Supreme Court in the Saraki case, given on 5 February, 2016, poses a problem for our constitutional system. The Court of Public Opinion, of which the media are a pillar, must rise to the occasion, and speak out – warns Professor Ben Nwabueze

MATTERS ARISING FROM THE SUPREME COURT JUDGMENT IN THE SARAKI CASE

INTRODUCTION

The Supreme Court, our apex court, has spoken in the Dr Bukola Saraki case, and its judgment, delivered on February 5, 2016 carries an authority that is unchallengeable, except in the court of public opinion, which is a vital bedrock of governance in a democratic society, such as we aspire to become. All of us, as stakeholders in the Nigerian state project, constitute the latter court, and have a duty to contribute to the discussion on the questions provoked by the Supreme Court judgment in the case.

The unchallengeability of the said judgment pre-supposes that it meets the standards of near-infallibility, conclusiveness and finality expected from a court of last resort, and that it is informed by the compelling need to ensure that decisions of the Court, as a court of last resort, are consistent with each other, and, above all, with the supreme law of the land, the Constitution, as well as with laws validly enacted by the legislature, all in the interest of the need, also imperative, for certainty and symmetry in the law and for its orderly development.

WHETHER THE SUPREME COURT DECISION ON THE ISSUE OF THE JURISDICTION OF THE CCT IS CONSISTENT WITH THE CONSTITUTION

The judgment in the Saraki case will now be critically examined against the standards and requirements stated above, beginning with the issue whether the decision is consistent with the law of the Constitution which, in affirmation of it supremacy, declares null and void, “any law “ that is inconsistent with its provisions : section 1(3). A court decision is indisputably a law within the meaning of section 1(3). The Supreme Court held, per Onnoghen JSC delivering the lead judgment, that “paragraph 18 of the 5th schedule to the 1999 Constitution as amended is replete with unambiguous terms and expressions indicating that the proceedings before the said of Conduct Tribunal are criminal in nature”, that “the said tribunal has a quasi-criminal jurisdiction designed by the 1999 Constitution”, and that “it is a peculiar tribunal crafted by the Constitution.”

The question arising is whether the Supreme Court is right in holding that the Constitution itself invests the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT) with a quasi-criminal jurisdiction. The decision is based partly on inference from the fact that many of the stipulations in the Code of Conduct in the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution are coached in prohibitory terms. But a close look at the Code shows that, notwithstanding the prohibitory terms of such stipulations, the Code is, in its essential character, simply a body of rules designed to regulate the civil, not criminal, behaviour of public officers, much in the fashion of the Civil Service Rules. The view that the Fifth Schedule invests the CCT with a quasi-criminal jurisdiction is negated by paragraphs 18(3) & (6) of the said Schedule, especially paragraph 18(3) which says that “the sanctions mentioned in sub-paragraph (2) hereof shall be without prejudice to the penalties that may be imposed by any law where the conduct is also a criminal offence” This suggests that the conduct proscribed by the Code is not thereby made a criminal offence.

In any case, it is not the purpose or role of a constitution anywhere in the world to create criminal offences, that being the function of the statute law. Conformably with the generally accepted role of a constitution, the Nigerian Constitution 1999 provides in section 36(12) that “a person shall not be convicted of a criminal offence unless that offence is defined and the penalty therefor is prescribed in a written law, and in this subsection, a written law refers to an Act of the National Assembly or a Law of a State, any subsidiary legislation or instrument under the provisions of a law” (emphasis supplied). The Constitution is not included. Accordingly, any criminal jurisdiction or “quasi-criminal jurisdiction” claimed for the CCT could not have derived from, or been conferred on it by, the Constitution.

The Supreme Court’s attribution of a quasi-criminal jurisdiction to the CCT is also inconsistent with section 6 of the Constitution, which vests judicial power in nine courts listed by name in subsection (5) and “such other courts as may be authorized by law to exercise jurisdiction on matters with respect to which the National Assembly [or a House of Assembly] may make laws”. The CCT is not one of the nine courts listed by name in section 6(5). Since it is established by the Constitution, and if it had been the intention that it should share in the vesting of judicial power, the Constitution should have mentioned it by name like the nine courts so named, instead of leaving it to be included by law made later by the National Assembly under the residual clause. It must be concluded therefore that the CCT does not partake in the vesting of judicial power; in other words, it is not one of the courts in which judicial power is vested by section 6 (1) of the Constitution – assuming it to be a court in the distinctive sense of section 6 of the Constitution.

The implication of this conclusion flows from the nature of judicial power and the incidents that are exclusive to it. The High Court of Australia (the highest court in that country) has held in Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia v. J.W. Alexander Ltd (1918) 25 CLR 434 at page 444, per Chief Justice Griffith for the Court:

“It is not disputed that convictions for offences and the imposition of penalties and punishments are matter appertaining exclusively to judicial powers.”

The word “exclusively” is underlined for purposes of emphasis. The learned Chief Justice has observed earlier in the judgment at page 442:

“It is impossible under the constitution to confer such functions upon any body other than a court, nor can the difficulty be avoided by designating a body, which is not in its essential character a court, by that name, or by calling the function by another name. In short, any attempt to vest any part of the judicial power…….in any body other than a court is entirely ineffective”.

As under the Constitution of Nigeria 1999, judicial power is vested in courts specified in section 6(5), it follows that the courts so listed are the only tribunals that can try and convict a person for a criminal offence under the principle laid down by the High Court of Australia in Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia v. J.W. Alexander Ltd, supra. The CCT, not being so listed, has no power or jurisdiction, derived from the Constitution, to try, convict and impose punishment on persons for a criminal offence; the decision of the Supreme Court attributing such jurisdiction to it, as jurisdiction derived from the Constitution, is null and void under section 1(3) of the Constitution; also any law made by the National Assembly that confers such jurisdiction on the CCT is null and void (see further below)

The principle of the decision in Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia v. J.W. Alexander Ltd, supra, as enshrined in sections 6, 35(1)(a) and 36(4) of the Constitution of Nigeria, has been affirmed and re-affirmed by our Supreme Court. Thus, in Sofekun v. Akinyemi (1981) 1 NCLR 135 where a public officer in the public service of the then Western Region of Nigeria was dismissed upon a finding of guilt for indecent assault and attempted rape by a disciplinary tribunal constituted and empowered in that behalf under the Public Service Commission Regulations, his dismissal was held null and void by the Supreme Court as a usurpation of judicial power.

In a judgment concurred in by Irikefe, Bello, Idigbe, Obaseki, Eso and Aniagolu JJSC, Fatayi-Williams CJN said at page 146:

“It seems to me that once a person is accused of a criminal offence, he must be tried in a court of law where the complaints of his accusers can be ventilated in public and where he would be sure of getting a fair hearing…..No other Tribunal, Investigating Panel or Committee will do…If Regulations such as those under attack in this appeal were valid, the judicial power could be wholly absorbed by the Commission (one of the organs of the Executive branch of the State Government) and taken out of the hand of the magistrates and judges….If the Commission is allowed to get away with it, judicial power will certainly be eroded……The jurisdiction and authority of the courts of this country cannot be usurped by either the Executive or the Legislative branch of the Federal or State Government under any guise or pretext whatsoever”. (emphasis supplied)

The decision was re-affirmed by the Court in Garba v. University of Maiduguri [1986] 1 NWLR (Pt 18) 550 where some students involved in acts of rioting and arson were expelled from the University. The Supreme Court, reversing the Court of Appeal and affirming the trial court, declared the expulsion null and void: first, since the expulsion was based on criminal offences alleged to have been committed by the students, only the court, but not the Visitor, Vice-Chancellor or the investigating panel set up by the University, is, by virtue of sections 6 and 33(1), (4) and (13) of the 1979 Constitution, competent to adjudicate upon the guilt or innocence of the students for the alleged criminal offences; second, whilst the University authorities may expel a student for misconduct not amounting to a criminal offence, yet as a disciplinary body, they are bound to act judicially, comply with the constitutional requirement of fair hearing and observe the other requirement of the rule of natural justice; in this case, the students were not given a fair hearing, and as the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, being a victim of the students’ rampage (his house was burnt down), his chairmanship of the investigating panel created a real likelihood of bias in that he was thereby put in a position of being both a witness and a judge all at the same time.

It is remarkable that, in Justice Onnoghen’s 37-page lead judgment, section 6 of the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s previous decisions in Sofekun v. Akinyemi (supra) and Garba v. University of Jos (supra), based on that section were not cited or considered. They were also not cited or considered in any of the other judgments delivered in the case. The judgments must be taken to have been given per incuriam, with the consequences noted later below. But the public deserves to know why. The issue of jurisdiction in the Saraki case cannot be settled aright without reference to section 6 and the decisions based on it.

WHETHER THE SUPREME COURT DECISION ON THE ISSUE OF THE JURISDICTION OF THE CCT HAS A BASIS IN A LAW VALIDLY MADE BY THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY

The Supreme Court decision attributing a quasi-criminal jurisdiction to the CCT was anchored not only on the Constitution itself, but also on the Code of Conduct Bureau and Tribunal Act. The question arising is whether the Act is consistent with the Constitution and valid. From what is said above, the Act is inconsistent with section 6 vesting judicial power in courts listed therein, of whom the CCT is not one. Apart from being inconsistent with section 6 vesting judicial power in the courts named therein, the Act is inconsistent with the Constitution for another reason, made so manifest by Onnoghen JSC in his lead judgment where he sets out the provisions of paragraph 15(1) of the 5th Schedule to the 1999 Constitution and section 20(1) of the Act, as follows:

Paragraph 15(1) : “There shall be established a tribunal to be known as Code of Conduct Tribunal which shall consist of a Chairman and two other persons”

section 20(1) : “There is hereby established a tribunal to be known as the Code of Conduct Tribunal (in this Act referred to as ‘the Tribunal’)

(2) “The Tribunal shall consist of a Chairman and two other members.”

It is obvious on the face of the two provisions that section 20 of the Act is a duplication of paragraph 15(1) of the Fifth Schedule, a fact so obvious as to make it unnecessary for counsel in their pleading or brief of argument to draw the Supreme Court’s attention to it. As earlier stated, the Supreme Court, as the court of last resort, has the duty, without special pleading or urging by counsel, to ensure that laws enacted by the legislature which it is called upon to apply in the adjudication of cases before it are consistent and not at variance with the supreme law embodied in the Constitution.

Given the obvious fact that section 20 of the Act is a duplication of paragraph 15(1) of the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution, only the legal consequences of such duplication remain to be determined. And the Supreme Court itself has determined them by its decision in Att-Gen of Abia State v. Att-Gen of the Federation (2002) 6 NWLR (Pt 763) 264 at 369, where the Court, per Kutigi JSC (later CJN), delivering the judgment of the Court, held :

“Where the provision in the Act is within the legislative powers of the National Assembly but the Constitution is found to have already made the same or similar provision then the provision will be regarded as invalid for duplication and or inconsistency and therefore inoperative. The same fate will befall any provision of the Act which seeks to enlarge, curtail or alter any existing provision of the Constitution. The provisions will be treated as unconstitutional and therefore null and void.” (emphasis supplied).

The decision is re-affirmed by the Court in INEC & Anor. v. Balarabe Musa & Ors [2003] 3 NWLR (Pt 806) 72 at page 158, where Ayoola JSC for the Court said:

“Where the Constitution has covered the field as to the law governing any conduct, the provision of the Constitution is the authoritative statement of the law on the subject…….Where the Constitution has provided exhaustively for any situation and on any subject, a legislative authority that claims to legislate in addition to what the Constitution had enacted must show that, and how, it has derived its legislative authority to do so from the Constitution itself. In this case, section 222 of the Constitution having set out the conditions upon which an association can function as a political party, the National Assembly could not validly by legislation alter those conditions by addition or subtracting and could not by legislation authorise INEC to do so, unless the Constitution itself has so permitted.” (emphasis supplied)

The decision of the Supreme Court in these two cases has a good rationale to support it. An inconsistency arises from the different sources of authority for the two provisions, one source of authority, namely the Constitution, being superior to the other i.e. an ordinary law made by the legislature; for this reason, a statutory provision, deriving authority from an inferior source, simply cannot exist and operate together with the same or similar provision in the Constitution which it duplicates. It makes hardly any sense that something established or existing by the Constitution should be established yet again by an ordinary law which is inferior to the Constitution; the basis of its existence, its character and authority is certainly not changed from the Constitution to the ordinary law, nor will the repeal of the ordinary law terminate its existence and powers under the Constitution.

This rationale finds further support in the decision which, based on the superior authority of a federal law vis-à-vis a state law on a concurrent matter, holds that where the Federal Government has legislated completely and exhaustively on such matter, so as to cover the entire field of the subject-matter, then, a state law on the same matter which duplicates the federal law is void for inconsistency, since the state law, deriving its existence from an inferior authority, cannot exist together with the federal law: Att-Gen of Ogun State v. Att-Gen of the Federation (1982) NSCC 1, particularly pages 11 (per Fatayi-Williams CJN delivering the judgment of the Court) and 28 (per Idigbe JSC). But see the judgment of Eso JSC who, dissenting on this point, holds that the identical state law is only in “abeyance” or in suspension, but not void: at page 35. Even on Justice Eso’s dissenting view that the duplicating state law is merely in abeyance or suspension, the provisions of the Code of Conduct Bureau and Tribunal Act, Cap 56 LFN, that duplicate those of the Constitution, being in abeyance or suspension, cannot be used as authority for the trial by the CCT of the offences charged against the Dr Saraki.

But there is another, perhaps stronger, reason for the unconstitutionality and nullity of an ordinary law that duplicates the provisions of the Constitution. Duplication, even when the duplicating provision in the ordinary law does not in terms purport to do so, imports by implication the supersession or supplantation of the provisions of the Constitution. To supersede or supplant means, according to the definition of the two words in Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language, “to replace in power, authority or use; to succeed to the position, function or office of.” By duplicating the provisions of the Constitution, therefore, the Act purports to make itself the governing power or authority in place of the Constitution as the governing law in use for all purposes.

In fact nearly all the provisions of the Act have the clear effect and manifest a clear intention of superseding or supplanting the provisions of the Constitution. Such, for example, are the provisions:

(i) establishing the CCB and the CCT (sections 1 and 20);

(ii) authorising the National Assembly to “confer on the Tribunal such additional powers as may appear to it to be necessary to enable the tribunal to discharge more effectively the functions conferred on it under this Act” (section 20(5); emphasis supplied); since they include the trial and imposition of punishment for a criminal offence, “the functions conferred on [the CCT] under this Act” are much greater than the functions conferred on it by the Constitution.

(iii) authorising the Tribunal to impose “any of the punishments specified under subsection (2) of this section” upon a public officer whom “it finds guilty of contravening any of the provisions of this Act” (section 23(1); emphasis supplied);

(iv) relating to the manner for exercising “any right of appeal to the Court of Appeal from the decision of the Tribunal conferred by subsection (4) of this section” (section 23(5); emphasis supplied);

(v) excluding “any punishment imposed in accordance with the provisions of this section” from the provisions of the Constitution relating to the prerogative of mercy.

The clear meaning and effect of these provisions and similar other provisions in most sections of the Act, such as those in sections 3, 6, 7, 9(1), 10(2), 15(1), (2) & (3), 16, 17, 18(1) & (2), 19, 21(1), & (2), 22(1), (3) & (4), 23, 24 and 25 is to replace the authority or use of the Constitution for this purpose with that of the Act. The Constitution ceases, to all intents and purposes, to be relevant or applicable, and is superseded or supplanted by the Act. On this ground, therefore, the Act, together with Charge No. CCT/ABJ/01/2015 based on it, is unconstitutional, null and void. The definition of “the Tribunal” in section 26 to mean “the Tribunal established by and under section 20 of this Act” is conclusive on this point.

The Act is even more glaringly unconstitutional and void because some of its provisions also purport to vary the provisions of the Constitution which they duplicate, as with the provisions establishing the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB) and prescribing its functions. The provision of section 1(2)(a) of the Act that “the Bureau shall consist of ……persons of unimpeachable integrity in the Nigerian society” is an addition to, and a variation of, the qualifications prescribed in section 156 of the Constitution.

Section 3(d) of the Act is at variance with paragraph 3(e) of the Third Schedule to the Constitution. For, whereas the latter empowers the CCB to “receive complaints about non-compliance with or breach of the provisions of the Code of Conduct………, investigate the complaint and where appropriate refer such matter to the Code of Conduct Tribunal”, (emphasis supplied) the Act omits the power to “investigate the complaint” and replaces the phrase “where appropriate” with the words “and where the Bureau considers it necessary to do so, refer such complaints to the Code of Conduct Tribunal established by section 20 of this Act in accordance with the provisions of section 20 to 25 of this Act.” (emphasis supplied). Needless to say, “where appropriate” confers a different kind of discretion from “where necessary”; what is necessary may not be appropriate. Furthermore, whereas under the Constitution the jurisdiction of the CCT can be invoked only by the CCB referring a complaint to it, under section 24(2) & (3) of the Act, on the other hand, proceedings before the CCT “shall be instituted” only by the Attorney-General of the Federation or by a person duly authorized by him.

It is again remarkable that neither the point about the inconsistency of the Act with the Constitution for the reasons stated above nor the decisions of the Supreme Court in Att-Gen for Abia State v. Att-Gen of the Federation, supra, and INEC & Anor v. Balarabe Musa & Anor, supra, were considered in any of the judgments delivered by the Supreme Court in the Saraki case, which must therefore be taken to have been delivered per incuriam, with the consequences noted later below. Passing reference was made to INEC v. Balarabe Musa, supra, Att-Gen, Ogun State v. Att-Gen of the Federation, supra, Att-Gen of Abia State v. Att-Gen of the Federation in the judgment of Muhammad JSC; to INEC v. Balarabe Musa, supra, in the judgment of Kekere-Ekun JSC, but the references were in relation to issues different from that of the unconstitutionality of the Act for inconsistency with the Constitution.

The consequences attendant upon a decision given per incuriam flow from the doctrine of precedent or stare decisis that governs the operation of our judicial system. A decision is said to have been per incuriam when it is given in ignorance or forgetfulness of a binding statutory provision or of a binding court decision or of a relevant provision of the Constitution with which the decision is at variance : so defined by Lord Esher MR in Morelle Ltd v. Wakeling [1955] 2 Q.B. 389 at p. 406. A decision given per incuriam lacks authority as binding precedent. In general, under the doctrine, the Supreme Court is bound to follow its previous decisions.

However, it may depart from its previous decision by a rigorous process that requires a written application praying it to do so where such previous decision “is shown to be (a) a vehicle of injustice; (b) or is given per incuriam; (c) clearly erroneous in law; (d) impeding the proper development of the law; (e) having results which are unjust, undesirable or contrary to public policy; or (f) inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution; or (g) capable of fettering the exercise of judicial discretion” : see Adisa v. Oyinwole (2000) 10 NWLR 116 at p. 207, per Iguh JSC.

WHETHER THE CCT, EVEN IF IT CAN RIGHTLY BE REGARDED AS A COURT, IS A COURT OF LAW WHICH ALONE UNDER OUR CONSTITUTION CAN BE INVESTED WITH CRIMINAL OR QUASI-CRIMINAL JURISDICTION

WHETHER THE CCT, EVEN IF IT CAN RIGHTLY BE REGARDED AS A COURT, IS A COURT OF LAW WHICH ALONE UNDER OUR CONSTITUTION CAN BE INVESTED WITH CRIMINAL OR QUASI-CRIMINAL JURISDICTION

The premise of the Supreme Court decision in the Saraki case, though one not explicitly articulated, is that the CCT is a court, a conclusion that flows, by implication, from the attribution of a quasi-criminal jurisdiction to it (i.e. the CCT). In taking this view, the Supreme Court failed to address the critical issue whether a court or tribunal, which is not a court of law, can, under our Constitution, be invested with criminal or quasi-criminal jurisdiction. It may be recalled that the Supreme Court the earlier cases of Sofekun v. Akinyemi, supra, and Garba v. University of Jos, supra, has decided that the trial of a person accused of a criminal offence must be by a court of law. What, then, is a court of law. And is the CCT a court of law?

Whether or not there is a difference between a court and a tribunal, and whether or not the CCT is rightly regarded as a court in the general sense, it is not, under our Constitution, a court of law, by which is meant a court composed of members required by law to be legal practitioners or lawyers learned and experienced in the law, who are versed in the difficult art of sifting evidence and judging the demeanour of witnesses, who are reared in the tradition of individual liberty inculcated in lawyers, which insists, rightly, that it is better for nine guilty persons to go free than for one innocent man to be punished, and who, finally, are obligated to adjudicate disputes according to law, or what is called justice according to law. This constitutes the cardinal marks of a court of law. For other essential attributes of a court of law, see Adeyemi v. Att-Gen of Oyo State (1984) 15 NSCC 397, per Bello JSC at page 401.

By paragraph 15(1) of the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution, the CCT consists of a Chairman and two other persons. But whilst the Chairman must be “a person who has held or is qualified to hold office as a Judge of a superior court of record in Nigeria”, the other two members are not required to be legal practitioners or lawyers; whether they are in fact lawyers or not (about which I have no information) does not really matter; what matters is that they are not required by the law of the Constitution to be legal practitioners or lawyers. The CCT is required to (or may) sit in a case with all its three members, including the two who are not required by law to be lawyers; all three have equal power in forming the decision of the Tribunal. It is a contradiction in terms to call by the name “court of law”, a tribunal consisting of three members, two of whom are not required by law to be legal practitioners or lawyers. Accordingly, the CCT, whether or not it can truly be regarded as a court in the general sense, does not qualify as a court of law by the definition above. As all the courts listed in section 6(5) of the Constitution consist of qualified lawyers with a prescribed minimum post-qualification experience, they qualify as court of law.

As just stated, the Constitution prescribes a qualification as a legal practitioner and a minimum post-qualification experience as a legal practitioner for the members of the courts which it establishes and invests with criminal jurisdiction – 15 years post-qualification experience for a member of the Supreme Court, 12 years for the Court of Appeal, 10 years for the FHC, and 10 years for the High Court of a State. The other courts named in section 6(5) do not count for this purpose since they are not invested with criminal jurisdiction, but qualification as a legal practitoner and a minimum post-qualification experience as a legal practitioner is nevertheless prescribed in their case, i.e. the Sharia Court of Appeal of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja; Sharia Court of Appeal of a State; the Customary Court of Appeal of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja; a Customary Court of Appeal of a State.

If the CCT is established by the Constitution as a court of law invested with criminal jurisdiction, the Constitution cannot, consistently with the qualification it prescribes for the other courts it establishes and invests with criminal jurisdiction, require only one, the chairman, of the three members of the CCT to be a qualified legal practitioner. This compels the conclusion that the CCT is not conceived and established by the Constitution as a court of law, and is not invested with criminal jurisdiction, even if only quasi criminal jurisdiction.

The conclusion that only a court of law, as defined, can try and convict persons of criminal offences is reinforced by section 174(1) of the Constitution which empowers the Attorney-General “to institute and undertake criminal proceedings against any person before any court of law in Nigeria.” The meaning is clear. If criminal prosecution by the Attorney-General or by anyone else, subject to the power of the Attorney-General to take it over or discontinue it, can only be instituted in a court of law, it follows that the Constitution requires that only a court of law can try and convict persons of criminal offences. The same conclusion and implication flows from the provision in paragraph 18(6) of the Fifth Schedule to the effect that “nothing in this paragraph shall prejudice the prosecution of a public officer punished under this paragraph or preclude such officer from being prosecuted or punished for an offence in a court of law” (emphasis supplied).It has been shown in the preceding paragraphs above that the CCT is not a court of law, and cannot therefore try and convict persons of criminal offences.

There are good, compelling reasons why, in a democratic system of government, limited by a constitutional protection of individual liberty, the trial of a person on a criminal charge brought against him by the state, as in the present case, should be conducted, not by a tribunal, which is not a court of law, but by a court of law characterised by the attributes mentioned above.

First, conviction and punishment for a criminal offence determine authoritatively and conclusively the standing of a person as a member of society, and punishes him by the infliction of physical pain, the deprivation of personal liberty or property. Conviction for a criminal offence carries a distinct “moral obloquy and social stigma”. It is an expression of society’s disavowal of his conduct as a deliberate flouter of its values, a condemnation of him as unworthy of its membership. “To be branded an anti-social is half-way to being deemed an outlaw”, see J.R. Lucas, On Justice (1980), page 138.

The moral obloquy and social stigma of criminal conviction have practical legal consequences. Criminal conviction brands a person with an indelible stamp of someone unfit to be employed, to be admitted into decent institutions or societies or to be trusted. The disability arising from a conviction is prescribed by the law itself in cases where the offences involve dishonesty. Thus, a person convicted of such an offence is disqualified by law from holding certain public offices or from functioning in certain capacities.

The imposition of punishment following upon a conviction carries the matter further, by giving society’s disesteem a tangible form in the way of some unwelcome action, like imprisonment. It thus gives weight to society’s verbal condemnation and disesteem of a person flouting its values.

To condemn and disgrace a person as a flouter of society’s values, and to punish him accordingly, imperatively requires that the process used must be such as is used in a court, learned and experienced in the law and characterised by the other attributes of a court of law specified above, a process that guarantees the independence and impartiality of the tribunal and the other safeguards of a fair trial, such as the presumption of innocence, the requirement of proof beyond reasonable doubt, the rules of admissibility or inadmissibility of evidence, impartiality etc. This is necessary to guard against as much as possible the possibility of an innocent person being convicted. The injustice of a false conviction and punishment is among the worst injustices imaginable.

WHETHER THE INITIATION OF THE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION AGAINST DR SARAKI BEFORE THE CCT BY A DEPUTY DIRECTOR IN THE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF JUSTICE AT A TIME WHEN THERE WAS NO INCUMBENT ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE FEDERATION (AGF) IS VALID AND COMPETENT IN LAW

The need for consistency as between the various decisions of our apex court in the interest of certainty in the law and its orderly development in order to avoid the confusion and chaos arising from conflicting or contradictory decisions of that Court could not have been more evidently underscored than in the judgments delivered in the Saraki case on the issue whether the prosecution of Dr Saraki before the CCT is validly initiated by a Deputy Director in the Federal Ministry of Justice at a time when there was no incumbent Attorney-General of the Federation (AGF).

The issue depends on the interpretation of section 174 of the Constitution which provides in its subsection (1) that the Attorney-General “shall have power (a) to institute and undertake criminal proceedings against any person before any court of law in Nigeria”; subsection (2) then goes on to provide that “the powers conferred upon the Attorney-General of the Federation under subsection (1) of this section may be exercised by him in person or [by him] through officers of his department.” The words “by him” are added by me to bring out the meaning more clearly. It must be borne in mind that the form of words in section 174(2) is the same as that in section 5(1) vesting executive power in the President.

To enable the meaning of the provision to be better understood, attention should be drawn to the title of section 174 appearing at the margin. It is captioned “public prosecutions”. The powers given to the AGF by section 174 relate solely, and are limited, to public prosecutions, i.e. prosecutions by and in the name of the state, the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN), as incarnating or personifying the public. The AGF’s power to initiate/undertake public prosecutions does not exclude a power in other agencies, corporate bodies or individual persons to initiate/undertake prosecutions which are not public prosecutions as defined, a fact implied in the provision empowering the AGF to take over or to discontinue any “criminal proceedings that may have been instituted by any other authority or person” : section 174(1)(b) & (c). The powers with respect to the control of public prosecutions are granted to the AGF as “the Chief Law Officer of the Federation and a Minister of the Government of the Federation”: section 150(1) which specifically so designates him, with qualification prescribed by section 150(2). The office of AGF and Minister of Justice is the only ministerial office specifically established by name by the Constitution.

The reason why the control of public prosecutions is vested in the AGF by the Constitution needs to be explained and understood to aid the interpretation of section 174. The reason for it is because public prosecutions often have sensitive and volative political dimensions and results affecting the relations between the Government and its opponents within the country and its international relations, necessitating that the decision to prosecute or not to prosecute certain cases or persons should be taken at the level of the Government, as advised and guided by the AGF as the Chief Law Officer of the Government and Minister of Justice. Section 174 cannot therefore be insightfully and correctly interpreted without due regard to the public interest or public policy considerations underlying the vesting in the AGF of the control of criminal prosecutions, which makes it undesirable that other officers in the Ministry of Justice, including even the Solicitor-General, should have the power to control public prosecutions. The sensitive and volatile nature of public prosecutions is reflected in the provision in section 174(3) that “in exercising his powers under this section, the Attorney-General of the Federation shall have regard to the public interest, the interest of justice and the need to prevent abuse of legal process”, a judgment which only the AGF as the Chief Law Officer of the Government and Minister of Justice can exercise.

On the issue under consideration, the Supreme Court held that the criminal prosecution against Dr Saraki before the CCT was validly and competently initiated by a Deputy Director in the Federal Ministry of Justice at a time when there was no incumbent AGF, relying on the previous case of FRN v. Adewunmi (2007) 10 NWLR (Pt 1042) 399 at pages 418 – 419 where Kalgo JSC, delivering the lead judgment, said:

“These sections though very similar in content do not require that the officers can only exercise the power to institute criminal proceedings if the Attorney-General expressly donated his power to them. The provisions of the sections presume that any officer in any department of the Attorney-General’s office is empowered to initiate criminal proceedings unless it is proved otherwise. This will not be in conflict with our decision in A.-G., Kaduna State v. Hassan (1985) 2 NWLR (Pt. 8) 483, where the main controversy was that there was no incumbent Attorney-General who could have donated the power to discontinue criminal prosecution in the case concerned.” (emphasis supplied)

The underlined part of the judgment was omitted in the lead judgment of Onnoghen JSC in the Saraki case, which made no reference at all to the Hassan case. No attempt was therefore made to give reasons for not following it or why it does not apply in the Saraki case. It should also be noted that the case of FRN v. Osahon (2006) 5 NWLR (Pt 973) 361 cited by the learned Justice has nothing to do with the issue before the Court for determination.

It is simply amazing that the Court in FRN v. Adewunmi, supra, should say that its decision in that case is not in conflict with the previous decision in Att-Gen, Kaduna State v. Hassan (1985) 2 NWLR (Pt 8) 483, when in fact there is a palpable conflict between the two decisions. In any case, the pronouncement in the Adewunmi case is merely an obiter dictum, as there was in the case an incumbent AGF who personally authorised in writing the initiation of the criminal prosecution against the accused person. The issue before the Court in the Saraki case on which the decision was based was not, therefore, before the Court in the Adewunmi case.

The facts of the case in the Hassan case were that a prosecution for culpable homicide of a boy was withdrawn by the Solicitor-General after committal on a preliminary investigation by a magistrate, who found a prima facie case to have been made against the accused persons. But the Solicitor-General thought the evidence at the preliminary investigation so contradictory as not to justify the prosecution being continued and accordingly withdrew it. The father of the dead boy, in a separate action in the High Court, then sought a declaration that only an Attorney-General or a person duly appointed to act in the office could withdraw or authorize the withdrawal of a prosecution without leave of the court, and that in the absence of an incumbent Attorney-General to authorise it, (an Attorney-General had not been appointed at the time) the withdrawal of the prosecution against the particular accused persons was unconstitutional and void.

The propriety of the exercise of the power by the Solicitor-General and other law officers in the Ministry of Justice turns on the provision that the powers conferred by the Constitution upon the Attorney-General in respect of criminal prosecutions “may be exercised by him in person or through officers of his department” (ss. 160(2) & 191(2)) 1979 Constitution. The interpretative question raised is whether the words “by him” govern both the exercise of the power by the Attorney-General in person and its exercise “through officers of his department” – whether, that is, what is meant is that the power may be exercised by the Attorney-General in person or by him through officers of his department. (emphasis supplied) The contention of the Solicitor-General was that the phrase “through officers of his department” confers upon the officers of the ministry an independent right to exercise the power, which does not depend upon delegation or authorisation by the Attorney-General.

Affirming the decision of the trial judge, the Federal Court of Appeal, by a majority of 3 to 1, rejected the interpretation contended for by the Solicitor-General. Such a view of the provision would clearly do violence to its true meaning and intent. In the context of the provision the word “through” pre-supposes a person who is to act through others. It implies a delegated authority or agency, the officers of the department being merely agents through whom the Attorney-General may act. Their acts done with his authority are presumptively his acts. In the contemplation of the law, the Attorney-General, provided there is one actually in office, is deemed always to be the person acting, whether the action is done by him in person or through officers of his department. As the learned President of the Federal Court of Appeal, Justice Nasir (formerly JSC), observed, “there is nothing in the Constitution to vest the exercise of the constitutional powers of the Attorney-General in any officer of his department without his authorisation” at p. 21 of his cyclostyled judgment; and there can be no such authorisation when there is no one holding or occupying the office or duly appointed to hold it in an acting capacity.

The contention that officers of the Attorney-General’s department have an independent right to exercise it runs counter to the provision that no person not qualified as a legal practitioner with at least ten years’ experience shall “hold or perform the functions of the office of Attorney-General”, in that, as Justice Wali (later JSC) pertinently observed, it will make it possible for officers without the prescribed qualification to exercise the power.

The decision of the Court of Appeal was affirmed by the Supreme Court in a judgment concurred in by all seven participating justices : Att-Gen of Kaduna State v. Hassan (1985) 2 NWLR 483. Delivering the leading judgment, Irikefe JSC said at page 503 :

“under section 191 of the 1979 Constitution, the exercise of the powers of the Attorney-General is personal to him and cannot be exercised by any other functionary unless those powers have been delegated to him by the Attorney-General. Before such delegation can take place, there must be an incumbent Attorney-General in office who can be donor of the powers.”

Oputa JSC is also quite categorical on the issue. He said at page 521 :

“I am fully satisfied that under Section 191(2), the powers conferred on the Attorney-General to withdraw proceedings under S.191(1)(c) can be exercised by the Attorney-General personally or by anyone he specifically delegated that power to withdraw any case. In the absence of such specific delegation, which is usually gazetted, no officer of the Department, not even a Solicitor-General, can withdraw a criminal case acting under Section 191 of the Constitution. It then follows naturally that where there is no incumbent Attorney-General, the powers given to him by Section 191 will, as it were, lie dormant. The question of delegation will arise only where there is someone, constitutionally competent, to make that delegation. Where therefore, as happened in Kaduna State during the period under review, there was no Attorney-General, the Solicitor-General, who cannot act without delegation from the Attorney-General, was acting unconstitutionally when he withdrew Charge No. KDH/28C/81 pending before Aroyewun, J. I am in complete agreement with the argument, reasoning and conclusion of my learned brother, Irikefe, J.S.C., in his lead judgment with regard to the issue whether or not the Solicitor-General of Kaduna State acted constitutionally in withdrawing the criminal case before Aroyewun, J., and I adopt same as mine. I will therefore uphold and affirm the judgment of the court of first instance (the judgment of Chigbue, J.) and the majority judgment of the Court of Appeal, Kaduna Division (which is the judgment of the Court) on the interpretation and application of Section 191 of the 1979 Constitution.” (emphasis supplied).

In his concurring judgment, Uwais JSC said at pages 513 – 514:

“There can be no doubt that the powers given to the Attorney-General of a State under section 191 of the Constitution belong to him alone and not in common with the officers of the Ministry of Justice. Such Officers can only exercise the powers when they are specifically delegated to them by the Attorney-General. The delegation usually takes the form of a notice in the Official Gazette. As there was no Attorney-General appointed for Kaduna State at the time material to this case, his powers under section 191 could not have been delegated to the Solicitor-General.”

The decision in this case applies to the exercise of all the powers of the AGF under section 174, including the power to initiate/undertake criminal prosecutions, and is not limited to the exercise of the power to discontinue prosecutions initiated by others.

The palpable conflict between, on the one hand, the decision in the Hassan case, and, on the other hand, the decisions in the Adewunmi case (or rather the obiter dictum) and the Saraki case has injected a state of confusion and chaos into the law, leaving it to the lower courts to choose which of the conflicting decisions to follow. As the decisions in Adewunmi and Saraki cases did not have due regard to the reason for vesting the control of public prosecutions in the AGF, and, in particular, to the directive in section 174(3) of the Constitution, the decision in the Hassan case is to be preferred.

The error in the Supreme Court decision on this issue is not cured by the Law Officers Act 2004 relied on by the Court. Sections 2 and 4 of the Act provide as follows :

“2. The office of the Attorney-General, Solicitor General and State Counsel are hereby created.

“4. The Solicitor General of the Federation in the absence of the Attorney-Genral of the Federation may perform any of the duties and shall have the same powers as are imposed by law on the Attorney-General of the Federation.”

The creation of the office of AGF by section 2 of the Act is a duplication of section 150(1) of the Constitution, and is, on the authority of Att-Gen of Abia v. Att-Gen of the Federation, supra, null and void for inconsistency with the Constitution. The power given to the SGF by section 4 of the Act is also null and void, being dependent on the existence of the office of the AGF as an office created by the Act.

Moreover, if the law on the meaning of section 174 is as decided by the Supreme Court in the Hassan case, then, that decision, being a decision on the meaning of a provision in the Constitution, becomes incorporated into the Constitution as part thereof, with the result that the meaning assigned to section 174 by the decision of the Supreme Court in the Hassan case cannot be changed by an ordinary law made by the National Assembly, from which it follows that the Law Officers Act 2004, to the extent that it purports to do so, is null and void on this ground as well.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The front page headline in the national newspapers, “Go And Face Trial, S’ Court Tells Saraki”, seems, frankly speaking, rather prejudicial to the interest of justice. There can be no question but that Dr Saraki must face trial for the criminal offences alleged against him. But he has a constitutional right, in the emphatic words of the Supreme Court in Sofekun v. Akinyemi, supra, (per Fatayi-Williams CJN), to” be tried in a court of law where………he would be sure of getting a fair hearing.” If the trial must be before the CCT, notwithstanding that it is not a court of law of competent jurisdiction, as shown earlier, he (Saraki) cannot be guaranteed a fair hearing before a tribunal already tainted by serious allegation of corruption against its Chairman, Danladi Umar, and on the part of which bias or a likelihood of it seems manifest. A court is supposed to be a sacred temple of justice, and those manning it should be untainted sentinels of justice. In a matter of such crucial importance in the affairs of the country, the Supreme Court should have taken judicial notice of the allegation of corruption leveled against Danladi Umar in the Sunday Vanguard of November 15, 2015, and should have directed that, if the trial of Dr Saraki must be before the CCT, then, Danladi Umar must step aside until he is cleared of the allegation of corruption against him.

The newspaper report discloses an investigation by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) of a N10 million corruption allegation involving Umar as chairman of the CCT and the former Deputy Controller-General of Customs, Rasheed Taiwo, N1.8 million of which had reportedly been paid by Taiwo and collected on Umar’s behalf by his personal assistant, Gambo Abdullahi. The newspaper report also disclosed that the two other members of the CCT, Robert Odu and Agwage Atedze, feeling so embarrassed by the allegation, had refused to sit with Umar, and that in a joint letter to former President Goodluck Jonathan, dated April 4, 2014, the two members had said as follows:

“May we with respect draw His Excellency’s attention to the allegation of N10 million bribe made against Justice Danladi Yukubu Umar, current chairman of Code of Conduct Tribunal, Abuja, which is being investigated by the EFCC.

“We, the two members of the CCT and the entire staff, are embarrassed and saddened by this allegation because a tribunal set up to check corruption should not be accused of being corrupt. This would not be in keeping with the transformation agenda of the administration.

“We are mindful of the fact that the Federal Government has zero tolerance policy for corruption, and this is the reason for the establishment of the CCT as one of the agencies to fight corruption in all its ramifications.

“It is our prayer therefore that this allegation will be looked into so that the tribunal can start sitting in the interest of litigants and their counsel.”

The Sunday Vanguard of November 15, 2015 further reported that, based on findings of its investigations on the matter, the EFCC raised a two-count charge against Umar and his PA, Gambo Abdullahi, but for reasons unknown, the Commission later dropped Umar’s name from the charge sheet and took only his PA to court, which left Umar to continue functioning as CCT Chairman and to preside over Saraki’s case, sitting with one other member, Agwadza Atedze, who earlier signed a letter declining to continue sitting with Umar.

The same Sunday Vanguard issue again reported that, based on the report and findings of the EFCC investigations, the former Attorney-General of the Federation (AGF), Mohammed Adoke SAN, wrote on May 7, 2015 to former President Goodluck Jonathan, as follows:

“I am of the humble opinion that the current state of affairs in which the CCT is unable to sit while the institution is increasingly diminished by a pall of suspicion, should not be allowed to fester as it will expose the institution to public ridicule and undermine this administration’s effort to combat corruption.

“IN the light of the foregoing therefore, Your Excellency may wish to initiate the necessary steps for the removal of the CCT chairman from office.”

What emerges from all these reports is that Umar faces a serious risk of prosecution and removal from office on corruption charges. The person who has the power to avert or to save him from the risk is the President who, as Head of State, personifies and incarnates the Federal Republic of Nigeria who, as the complainant in the criminal prosecution against Saraki, is a party to the proceedings. This naturally would create an inclination on the part of Justice Umar, as Chairman of the CCT, presiding over Saraki’s case, to want to use the case to ingratiate himself with President Buhari to get him to save him (Umar) from the threatening risk of prosecution and removal from office. Saving himself from the risk of prosecution and removal from office creates in Umar a personal and even a pecuniary interest in the case, in the form of his remunerations and other perquisites of office, which would incline him to want to favour FRN against Saraki. See on this, Adebesin v. State (2014) 4 S.C. (Pt 111) 151. In addition, FRN, personified and incarnated by President Buhari, is Umar’s employer and Umar is its employee. It has been held by the Court of Appeal in Adio v. Att-Gen Oyo State (1990) 7 NWLR 451 that the employer-employee relationship is a circumstance that gives rise to bias. It is not reasonably to be supposed or be expected that Justice Umar can be impartial or unbiased in adjudicating the case between the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN) against Saraki. There can be no greater mockery of the whole notion of impartiality in any adjudicatory system than that Umar, with the threat of prosecution and removal from office by the FRN hanging over his head, should have been allowed to adjudicate as presiding judge in the circumstances of this case. Bias on the part of Umar seems to be clearly manifest in all the circumstances surrounding the case.

Besides, the manner in which the trial was being conducted by Umar manifests also a certain overzealousness that suggests at least a real likelihood of bias on the part of Umar against Saraki or a lack of impartiality – as, for example, the hostile attitude towards Saraki’s request for stay of proceedings based on his objection to the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, as manifested in (a) its refusal to accede to the request; (b) its refusal to obey the FHC’s order dated 17 September 2015 to appear before it to show cause why the proceedings should not be stayed; and (c) its going ahead, in spite of (a) and (b) above, with the proceedings, by issuing a bench warrant for Saraki’s arrest on 18 September, 2015, leading to his team of lawyers walking out from the proceedings in protest and to the Supreme Court eventually staying the proceedings. The speed and what appeared to be a desire to conclude the trial as hastily as possible, as if conviction and the removal of Saraki as Senate President were the pre-determined purpose of the prosecution and trial. These clearly are circumstances from which a real likelihood of bias may be inferred.

As the Court of Appeal held in Omoniyi v. Central School (1988) 4 NWLR (Pt 89) 458, “the term ‘real likelihood of bias’…must mean at least ‘a substantial possibility of bias.’” The Court adopted the words of Lord Denning MR in Metropolitan Properties Co. Ltd v. Lannon, [1969] 1 Q.B. 577 at p. 599, as follows :

“In considering whether there was real likelihood of bias, the Court does not look at the mind of the justice himself or at the mind of the chairman of a tribunal, or whoever it may be who sits in a judicial capacity. It does not look to see if there was a real likelihood that he would, or did, in fact favour one side at the expense of the other. The Court looks at the impression which would be given to other people. Even if he was impartial as could be, nevertheless, if right-minded persons would think that, in the circumstances, there was a real likelihood of bias on his part, then he should not sit. And if he does sit, his decision cannot stand.

However, it is necessary that there must be circumstances from which a reasonable man would think it likely or probable that the justice, or chairman, as the case may be, of a tribunal would or did favour one side unfairly at the expense of the other. The Court will not inquire whether he did, in fact, favour one side unfairly. Suffice it to think that people might think it did. The plain reason for this is that justice is rooted in confidence; and confidence is destroyed when right-minded people go away thinking: the Judge is biased.”

Thus, in this case, if actual bias is not present, a real likelihood of it does clearly exist.

When bias or the likelihood of it is present in a case, as in the Saraki case, its effect, as the Court of Appeal held in Denge v. Ndakwoji (1992) 1 NWLR 223, is not only to diminish the stature and integrity of the judge, but also to destroy the foundation of his judgment, however sound and consistent with the Rules of Court, pleadings and evidence”, citing in support Omoniyi’s case, supra. In more precise terms, it vitiates the entire proceedings. “If actual bias is proved”, the Supreme Court held in a 2014 case, Adebesin v. State (2014) 4 S.C. (Pt 111) 152, “the proceeding is flawed and vitiated for contravention of section 36 of the Constitution of Nigeria 1999:” see the numerous other decisions to the same effect cited in the above cases.

Professor Ben Nwabueze,

Lagos

16th February, 2016