By Chido Onumah

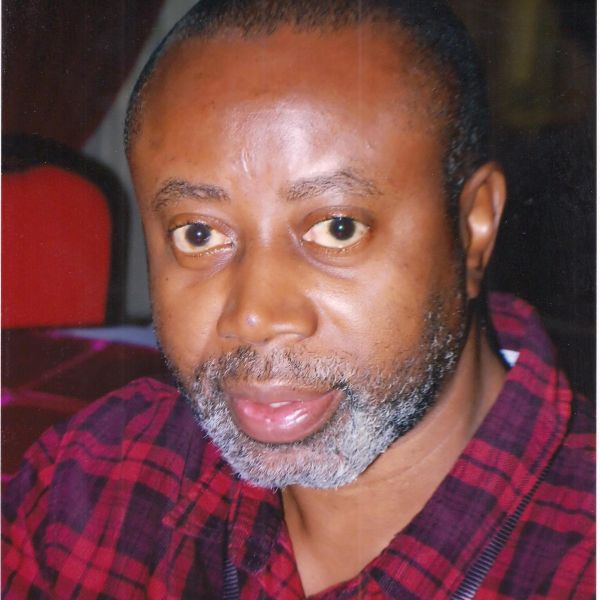

Two weeks ago, I lost a comrade, brother, and friend, Innocent Chukwuma. Innoma, as I called him, was 55, and until a few months ago when he retired, the regional director (West Africa) of Ford Foundation. Every waking moment in the last two weeks has left me thinking about life and Innocent Chukwuma’s death.

I had a busy day on Saturday, April 3. Earlier that day, my spouse had informed me of the news of the death of the political activist, Yinka Odumakin, national publicity secretary of Afenifere, the Pan-Yoruba socio-cultural group. At 2:22 p.m. Pacific Standard Time, I was about to put my phone on flight mode for a nap when I received a message from Dr. Chidi Odinkalu. The first message read: “Good evening sir. How are you doing?” It was followed by two questions; all three messages in a space of one minute: “Family?” “Have you heard about Innocent…? I replied immediately, “Good. Thanks. Innocent?” I became apprehensive when I didn’t get an immediate reply. My apprehension soon turned into distress. I couldn’t take my eyes off the phone. A minute later, I sent another message: “Are you there?” I asked. No response. My anxiety increased. I was about to dial his number when Dr Odinkalu called with the devastating news. “We may have lost Innocent,” he intoned. My stomach tightened. I didn’t know how to process the news. All I could ask was, “When, how, what happened?” He went on to explain how Innocent had taken ill and had been diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) two days earlier and was about to start chemotherapy the day he died.

I first came across the word leukemia many years ago in an article about the death of Frantz Omar Fanon, the psychiatrist and political philosopher from Martinique. Fanon died of leukemia in the US in December 1961 after military expeditions in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. He was 36. For many in my generation, Fanon was the quintessential primer for political education. In his seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon admonished: “Each generation must out of relative obscurity discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.” In life, Innocent Chukwuma epitomized the words of Fanon, one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. He discovered his mission and fulfilled it, and he is deservedly being honoured in death.

A lot has been written about Innocent and his contribution to the civic space in Nigeria and outside. Every sector has a story to tell about his impact. I have nothing to add. My tribute is to pay homage to our friendship, his humanism and good-naturedness. Innocent and I became close the moment we met. We had a relationship that bordered on brotherly love. I don’t know what it was, but we seemed like kindred spirit. Many years ago, in the middle of a conversation about the trouble with Nigeria, he averred that a big part of the trouble with Nigeria started in 1966 when the first military coup took place, propelling a chain of brutal events — including a civil war — that have left the country comatose. He proposed that those of us born in 1966 — we were born two months apart — should spearhead the effort at national redemption. He then suggested the formation of a group, the Class of 66, to undertake that task.

Like many in our generation, we met and became friends in the student movement. Our first contact must have been in 1988, but what I remember now is how he frequented my hostel at the University of Calabar in the late 80s for refuge anytime he was in “trouble” at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Fate would bring us together again exactly thirty years ago at the Kashim Ibrahim College of Education, Maiduguri, Borno State, for our national service. It was a great reunion. I worked as a reporter with the camp radio. I needed an ally like Innocent to stand up to the highhandedness of the impetuous camp commandant. Just as he did in secondary school, he led the quest to ensure that corps members got what they were supposed to get at the cafeteria. And he was always willing to be interviewed by the camp radio. For our actions, we were “punished” and posted to far-flung places. He was posted to Monguno for his primary assignment while I was posted to the remote village of Kwajafa, Biu, about 200 kilometres from Maiduguri.

While Innocent was keen on national service, the dreary condition in Monguno left him with no choice. He returned to Lagos. I wanted to explore. Even though I had travelled extensively across the country as vice president, special duties, of the National Association of Nigerian Students in 1989, up until my posting, I had not been to Borno and Sokoto states. After a few months in Kwajafa, I redeployed to Maiduguri and travelled to Sokoto State immediately after service and then back to Lagos where I reconnected with Innocent who had spent the remainder of his service year at the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO).

I visited the CLO office regularly to see Innocent and other friends. During each visit, he would ensure that I had the latest publications and materials I needed to file stories on the human rights situation in the country. When I joined The News in 1995, Innocent’s three-bedroom apartment at Cement Bus Stop in the Iyana Ipaja area of Lagos became my weekend hangout. Every Friday, after work, I would head to the apartment he shared with hometown friends, Geoffrey Anyanwu and Okey Nwanguma, Executive Director of Rule of Law and Accountability Advocacy Centre (RULAAC).

Innocent Chukwuma loved life and he enjoyed it to the fullest. You couldn’t get bored in his company. He had a joke as a solution to every problem. His uproarious humour stood him out in every gathering. He loved to curse in Igbo, but not out of anger or disrespect. The fecundity of his mind reminded you of a griot, the repository of oral tradition in West Africa. Innocent was friendly and accessible. The influence he wielded did not change his disposition towards friends or younger associates.

When he took up the job at Ford Foundation eight years ago, he called to inform me. About the time he joined Ford Foundation, my teacher, mentor, and current chair of the Spanish Radio and Television Corporation (RTVE), José Manuel Pérez Tornero, invited me to apply for a doctoral programme in communication and journalism at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), Barcelona, Spain. I was 47. I told Prof. Tornero that I was not interested in taking up the offer. Even though I had been a part of the faculty of UAB’s Journalism Summer School for a few years prior to 2013, I was not planning a life as an academic. Prof. Tornero persuaded me and pledged his support.

Three years into the programme, I was at my wits’ end. Living in Canada, studying in Spain and working in Nigeria had left me mentally and financially drained. Worse still, instead of focusing on school, I had spent the early part of 2016 working on a book. A few days after the book was published in May 2016, I called Prof Tornero who was my supervisor and informed him of my plan to abandon the programme. He was alarmed. He insisted that I had to finish the programme if it meant switching to part-time. What I didn’t tell him was the financial strain, particularly travel cost. Amid my turmoil, Innocent had called to invite me to an event he and his spouse, Josephine, were planning for their 50th birthday in Lagos. He tried to cheer me up by telling me that Dr. Matthew Hassan Kukah was the keynote speaker and that while in Lagos he would arrange some television appearances to promote my book.

We had a great time. It was an opportunity to meet friends we had not seen for many years and to reminisce about life as students. Unfortunately, I lost a bag containing personal effects. When the party ended, I went to Innocent and Josephine to tell them what had happened. While Josephine was comforting me, Innocent was teasing me that I had enjoyed myself so much that I had lost my belongings. The couple arranged for a hotel accommodation for the night and came back the following day to take me out to lunch. During lunch, Innocent asked about my research and when I was planning to finish my programme. I explained my situation and the decision to abandon the programme. Typical of him, he teased me about the effect of “adult education.” For someone who described himself as a “lifelong learner,” I knew he was only being mischievous. He asked me the most pressing need concerning my programme. I told him I needed fund to travel to South Africa and Spain to complete my field research. He said if that was the only problem, I had no reason not to finish the programme. He said he would ask his people to get in touch with me. Before I left Lagos, I received an email from Ford Foundation asking me to fill out a form for a research grant. That grant enabled me to complete my programme.

Innocent was a big man, tall and imposing. But it wasn’t just his frame that defined him. He was a man of ideas, big ideas. He was also practical in every sense of the word. There was hardly any problem Innocent did not have a solution to. Whether you agreed with him or not, you had to respect the depth and originality of his ideas. A few years ago, during a conversation on the political turmoil in Nigeria, he told me how worried he was and that he was planning to discuss with the country’s business elite to support the quest to rein in the political class to save the country. I told him I shared his idea. You couldn’t argue with that. The business community needed a safe environment for their business to thrive. Much earlier, he had shared with me his idea of the Oluaka Institute in Imo State, a technology incubation village which he set up to bridge the technology gap and tackle youth unemployment.

In 2019, when the current government and its spokesperson, Lai Mohammed, upped the ante in their anti-press rhetoric, I spoke with Innocent about the need to do something. He asked me to share a concept note for a conference to address the challenge of the shrinking media and civic space in Nigeria. That conference held in November 2019 with the support of Ford Foundation, Amnesty International, and Open Society Justice Initiative.

A month after the conference, I shared the idea of a book project to mark Nigeria’s diamond jubilee. He found the project fascinating. Then COVID-19 struck, causing major dislocation globally. For a while I didn’t hear from Innocent. Then, last September, I got a call from him asking if I was still keen on the book project. I told him we had started the project with support from the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA). He offered to lend additional support through Ford Foundation. The result is the book, Remaking Nigeria: Sixty Years, Sixty Voices, a collection of essays by post-civil war Nigerians on what ails the country and how to tackle it. A day before I received the news of his death, I had planned to send him an advance copy of the book through a mutual friend returning to Nigeria from the US. I didn’t know death had other plans. Innocent’s death reminds us of our mortality; his life, a testament to selfless service and its impact on humanity.

A man close to his roots, Innocent never stopped talking about retiring to his village in Mbaise in Imo State and starting a local musical group. I still remember teasing him about it during his farewell party at Ford Foundation a few months ago. Whether he meant it or not, we will never know. What we know, sadly, is that we have lost our Innocent, and it hurts!

Onumah is the Coordinator of the African Centre for Media & Information Literacy (AFRICMIL). Twitter: @conumah