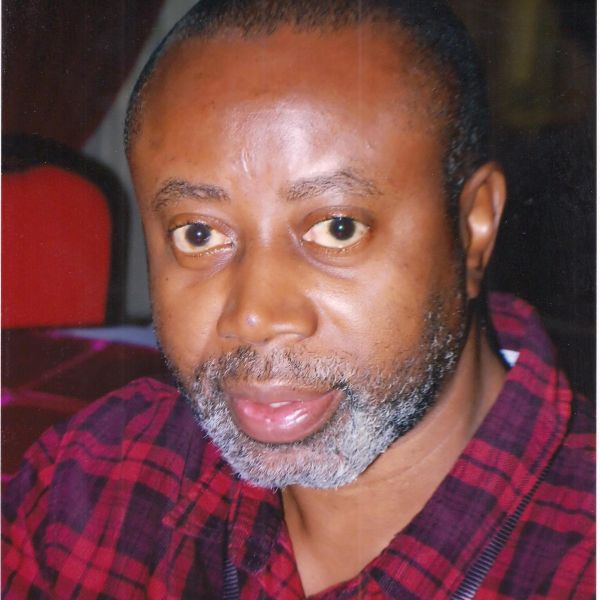

By Chido Onumah

Introduction

To paraphrase the historian, mathematician, journalist, and public intellectual, Edwin Madunagu, every political history has its significant dates, landmarks or turning points. In Nigeria’s political history, for instance, landmarks would include October 1, 1960, (the day Nigeria gained independence from Britain), January 15, 1966, (when the first of what would become a tradition of military coups occurred), July 6, 1967, (the official start of the 30-month Nigeria-Biafra war) and January 15, 1970, (the official end of the civil war).

To these dates, I will add January 1, 1914, (the amalgamation of the Southern and Northern Protectorates by the British to create Nigeria), May 27, 1967, (the beginning of state creation in Nigeria), and May 30, 1967, (the official declaration of the secessionist state of Biafra). The latter dates, May 27 and May 30, 1967, are significant in many ways. On May 27, 50 years ago, Yakubu Gowon, who served as head of state of Nigeria from 1966 to 1975, perhaps in anticipation of the audacious move by the Military Governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, Lt. Col. Emeka Ojukwu, announced the division of Nigeria into 12 states from four regions. The division of Nigeria into 12 states and Ojuwku’s declaration of Biafra were decisions that would change the country forever.

Gowon’s action did not only alter the structure of Nigeria, it led to the reconstruction of the nascent nation through the lenses of the so-called Nigerian military; a military that was provincial in outlook as it was ill-equipped for leadership. The military centralized economic and political power and moved Nigeria from a federal republic to a unitary state. In many ways, we can conveniently say May 27, 1967, was the day Nigeria began to unravel and any attempt to understand the current crises and our inability to make progress as a nation must necessarily return to the action of the military junta on May 27, 1967.

The road to Biafra

Three days later, May 30, 1967, Lt. Col Ojukwu, a Nigerian soldier of Igbo extraction declared an “independent sovereign state of the name and title of Republic of Biafra,” officially excising the Eastern Region from Nigeria. Ojukwu based his action on the resolution, four days earlier, on May 26, 1967, of a joint conference of the Eastern consultative assembly and leaders of thought that asked him to declare the Eastern region as separate republic at an “early practicable date”.

The declaration of Biafra was the culmination of a series of tragic events. First was the bloodletting that started with the January 15, 1966, military coup. That coup led to the assassination of Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Belewa, the country’s first and only prime minister and Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Premier of the Northern Region, among other high-profile casualties. Some recollections by Edwin Madunagu in “Settling account with Biafra” (The Guardian, May 4, 2000) are apposite here: “One, the politics of the First Republic (1960-1965) was heavily characterised by ethnicity, especially towards the end of that tragic period. Two: Of the five army majors that are more frequently mentioned as leading the coup attempt, only one, Major Adewale Ademoyega, was non-Igbo by ethnic origin. Three: No Igbo political leader died, and the only Igbo military casualty occurred not because he was a target but because he was considered a ‘nuisance’. Four: The attempted coup was the culmination of a long period of political crisis in Nigeria, a crisis whose centre of gravity was Western Region where, before the military intervention, the crisis had become an armed popular uprising.”

On July 29, 1966, there was another military coup led by officers from Northern Nigeria and Lt. Col Yakubu Gowon became head of state. According to Madunagu, the coupists “first made a move to pull the Northern Region out Nigeria, but when they were advised that they were now in a military situation to rule the whole country, instead of a part of it, they dropped the idea of secession and became champions of ‘One Nigeria’. Lt. Col Ojukwu refused to recognise Lt. Col Gowon as head of state.”

The second coup led to the assassination, among other high-profile casualties, of the country’s first military head of state, Gen. Aguiyi Ironsi, an Igbo, as well as the military governor of the Western Region, Lt. Col. Adekunle Fajuyi. This was followed by, as Madunagu notes, “mass killings not only in the North, but all over the country, except the Eastern Region. Now, multiply the May 1966 tragedy by a factor of 50, add to it the fact that the killings were now led by armed soldiers whose commanders were now in power and add to this the fact that the killings did not abate for at least five months and you begin to have an idea of what happened.”

The criminal indifference of the Nigerian state to the manifest pogrom against people from Eastern Nigeria, particularly Igbos, the repudiation by the Nigerian contingent (and the “unilateral implementation” by the Eastern regional government) of the agreement on decentralization of power reached at a meeting in Aburi, Ghana, involving the main protagonists, Yakubu Gowon and Emeka Ojukwu, at the instance of Gen. Ankrah of Ghana, finally paved the road to Biafra.

The accounts of what took place in those turbulent days are as varied as there are ethnic groups in Nigeria. But one thing is certain: the effects of those events, particularly the actions of May 27 and 30, 1967, are still being felt today. In one fell swoop, the military unilaterally restructured Nigeria according to its dictates. While Ojukwu drafted “unwilling” minorities in the Eastern Region to create a Biafran state where Igbos were in the majority, the Nigerian military which was nothing but the armed wing of a reactionary feudal class that had power thrust on it at independence began the implementation of an agenda of conquest. Interestingly, barely a year earlier, the section of the military that seized power after the January 15, 1966 coup had attempted to reconstruct Nigeria as a unitary state with the promulgation of the unification decree 34 of 1966. That attempt was opposed fiercely by those (including a section of the military) who felt they had lost out in the power equation. The rest is history.

When history repeats itself

Unfortunately, Nigeria is on the cusp of that tragic history repeating itself. Regrettably, 50 years after the declaration of Biafra many young Nigerians of Igbo descent are trying to recreate Biafra. A few months ago there were events in Nigeria and around the world to mark the 50th anniversary of the declaration of Biafra on May 30, 1967. Forty-seven years after the end of the Nigeria-Biafra War, Biafra still resonates with individuals and groups within and outside the country; perhaps, a testament to the fact that the war hasn’t ended in the minds of the protagonists and victims and the reality that many of the issues that propelled the civil war are still with us today.

So, how do we deal with this conundrum? Is Biafra the solution? In other words, can we solve the problems of 2017 Nigeria using the tragic solution of 50 years ago? As S.M. Sigerson noted in The Assassination of Michael Collins: What Happened at Béal na mBláth? “A nation which fails to adequately remember salient points of its own history, is like a person with Alzheimer’s. And that can be a social disease of a most destructive nature.”

Seventeen years ago, Edwin Madunagu, in the piece referenced above, admonished “the young Nigerians now threatening to actualise Biafra (to) forget or shelve the plan. In place of ‘actualisation’ they should, through research and study, reconstruct the Biafran story in its fullness and complexity and try to answer the unanswered questions and supply the missing links in the story. This is a primary responsibility you owe yourselves: you should at least understand what you want to actualise. If 30 years after Biafra, you want to produce its second edition, you need to benefit from the criticism of the first. History teaches that a second edition of a tragic event could easily become a farce—in spite of the heroism of its human agencies. On the other hand, those who enjoy ridiculing Biafra—instead of studying it—are politically shortsighted. My own attitude to Biafra is neither ‘actualisation’ nor ridicule. I propose that accounts should be settled with Biafra.”

Madunagu’s admonition needs no elaboration. It is clear enough for the young people pushing for the actualisation of Biafra, many of whom were born after the end of the Biafra war 47 years ago. The aspect of his position on Biafra that I want to focus on is the aspect that warns of the “political shortsightedness of ridiculing Biafra.”

To be continued Wednesday …

Onumah is the author of We Are All Biafrans. This essay was written in 2017 as part of a conference presentation. It is being published now because of its relevance to Nigeria’s current situation.