By Jeph Ajobaju, Chief Copy Editor

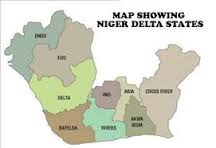

In February, 42,500 residents in Ogale and Bille, farmers and fishermen who rely on the waterways of Ogoniland in Rivers State, obtained the right to sue Shell in courts in England for environmental pollution that has decimated their livelihoods.

Shell Chief Executive Ben van Beurden announced in May that the oil giant would divest interest in onshore fields in Nigeria and was in talks with Abuja to sell off its stakes in the Niger Delta.

Those stakes date back to 1956 when Shell became the first major firm to discover oil in commercial quantity in Africa’s largest economy.

Before Beurden spoke in May, Shell had already joined ExxonMobil, Total, Eni, and other oil majors to slash billions in spending after dips in their profits in Nigeria and began relocating money to renewable fuels, focusing on cost-effective markets.

Counter claims

Financial Times reports that Buerden’s announcement heralded the end of an era in Nigeria as it was Royal Dutch Shell that discovered oil at Oloibiri in the swamps of the Niger Delta and helped turn it into a posterchild for the resource curse.

Beurden blamed the winding down on the risk profile of the delta, which has been wracked by communal tensions and criminality for generations.

“We cannot solve community problems in the Niger Delta – that’s for the Nigerian government perhaps to solve,” he said.

“We can do our best, but at some point in time, we also have to conclude that this is an exposure that doesn’t fit with our risk appetite any more.”

But Ledum Mitee, former head of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), insists that “they [Shell] certainly have a responsibility to solve the problems in the Niger Delta caused by their activities.”

Shell – operator of Nigeria’s onshore oil and gas joint venture, Shell Production Development Company (SPDC) – has struggled for years with spills in the Niger Delta as a result of pipeline theft and sabotage as well as operational issues.

Reuters recalls that the spills have led to costly repair operations and high-profile lawsuits.

In February, a Dutch court held SPDC responsible for multiple oil pipeline leaks in the Niger Delta and ordered it to pay unspecified damages to farmers, leading Beurden to call its Nigerian onshore assets as a “headache”.

Last year Shell also lost a Nigerian high court case that could lead to $44 million in damages for spills.

SPDC has sold about 50 per cent of its oil assets over the past decade. Shell’s stake in SPDC gave it 156,000 barrels per day (bpd) of oil equivalent in 2020, of which 66,000 barrels were oil.

Shell’s contribution to Nigerian economy

The delta is full of lush mangroves sprouting from water that shimmers with an oily, rainbow sheen. While crude worth billions has been extracted from its shores, it shows few signs that the industry has operated there for decades, reports Financial Times.

Yet it is rife with “community problems,” newspaper adds.

The problems have flowed alongside its oil, which has wrought economic and environmental devastation, sowed poverty, destroyed farmland and fisheries, enriched corrupt politicians and strengthened organised crime syndicates.

For many who live there, the region is what it is today in large part because of Shell.

The company “has huge historical and legacy issues with communities . . . that cannot be wished away,” says Mitee.

“They certainly have a responsibility to solve the problems in the Niger Delta caused by their activities.”

He took over MOSOP from Ken Saro-Wiwa, the celebrated activist and writer who led a peaceful protest seeking justice for the Ogoni over the environmental devastation of their homeland until Sani Abacha executed him and eight others in 1995.

“There is no doubt in our minds that Ken and my [other] colleagues were executed for the purposes of making it possible for Shell to operate without hindrance,” Mitee tells Financial Times.

A Shell spokesperson says the company has “always denied, in the strongest possible terms” any responsibility for the state’s executions of the Ogoni Nine.

Shell argues that it contributes to Nigeria’s economy. It has 2,700 employees and more than 9,000 contractors, and paid $4.6 billion into the country’s coffers in 2019 alone.

The company says its withdrawal from onshore production would be done in collaboration with the government and local communities, and it will continue to meet its obligations for oil spills.

“The challenges of the Niger Delta are complex and widespread, affecting communities where we may never have operated,” the spokesperson says to Financial Times.

“Where we do operate, we bring jobs, support local supply chains and invest in the education and healthcare people rely on, as well as providing billions of dollars in income to the Nigerian government.”

Convenient scapegoat

The perception that Shell has been a negative actor has made it a convenient scapegoat for Nigeria’s corrupt political class, says Idayat Hassan, head of the Abuja-based Centre for Democracy and Development.

“The problem is that of lack of governance, not just business,” she says.

Mike Karikpo, a delta-based lawyer with Friends of the Earth International, helped negotiate a long-delayed, billion-dollar clean-up of Ogoniland, which is largely funded by Shell and the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) but has been wracked by allegations of graft.

“We hold the company accountable for nearly 70 years of reckless and self-regulated operation in our communities,” Karikpo says.

“No matter how much Shell tries to evade responsibility for the destruction of our ecosystem, local livelihoods and the sociocultural fabric of our communities, it will fail.”

Karikpo points to a landmark Dutch court judgment which held Shell’s Nigerian subsidiary liable for oil spills in the delta and could open the door for more such cases. “Shell must pay for the clean-up and restoration of our environment,” he says.

“It is debt it owes our generation and future generations of people in this region and it is debt we will work diligently and strongly to extract to the very last dime.”