Akachi Adimora Ezeigbo’s Roses and Bullets takes off like a plane on a tarmac, slowly. War meets ordinary people suddenly, disrupting their personal plans. Ginika, Eloka, Nwakire and others are students when the war breaks. Eloka’s father, a farmer has to leave his big farm to run for his dear life and Chito’s husband is a teacher. No matter what you are engaged in, war will forcefully stop you.

So, the novel opens with Ginikanwa, a stereotypical motherless young woman whose father has remarried. She’s in her Auntie’s house in Enugu, the coal city in south east Nigeria. War has just broken and her father comes to fetch her in a brutish manner typical of unaffectionate insensitive and harsh fathers. In the words of Ginika, “Papa is completely unapproachable, utterly impossible.” Ginika prefers her mother’s sister’s (Auntie Chito) house to her father’s house for obvious reasons.

Eloka Odunze shares the same father problem with Ginika. That’s the typical African father figure – foreboding, intimidating; only interested in instilling discipline and sensibility in their offspring – no love. While the African mothers are the hands that guide the way, fathers provide the hand that keep in the way.

The novel tackles a lot of human related issues like raising a young woman at wartime, and how ordinary people live at wartimes, including soldiers who people depend on to keep the battles faraway. – How serious are these soldiers?

Ezeigbo like a weaver touches every aspect of human life as seen in different relationships: difficult and unfriendly fathers, hateful stepmothers and mothers-in-law, conditional love, dysfunctional love (Ginika and her father; Nwakire and his father; Eloka and his father; Eloka’s mother and Ginika, Auntie Lizzy and Ginika, Ginika and Philomena depicting young people’s struggles with their sexuality, Lieutenant Kanu Ofodile (trainer of special constables), Lieutenant Ugoro (Army Camp, Nkwerre) and the soldiers who came in defence of Sergeant Sule Ibrahim – these represent hawks hovering over growing young women, etc.). Also, the reader has a glimpse of love as it should be between Tonye and her father, Nwakire and Ginika, Auntie Chito and Ginika, Auntie Chito and her husband, etc., plus, shocking deaths.

The author looks at love’s strength when things go awry. Ezeigbo asked the silent question, ‘How strong is your love? Can it stand in the evil day?’ Dr Ubaka loves his daughter, Ginika and Eloka loves his wife, very much. But how strong is this love? Dr Ubaka’s love for his daughter, Ginika is passionate, self-centered and violates boundaries. As long as she remains a virgin until she goes off to the care of another man, he’ll love her. Once something goes wrong, whether it’s her fault or not, she’s on her own. He doesn’t even want to hear the story! Dr Ubaka’s door slams against his daughter’s face because she said that someone raped her!

Eloka, on the other hand, finds no place in his heart to receive his wife because someone touched her even as she explained and explained.

Ezeigbo shows that war does not annihilate love relationships – as long as there is life and the opposite sexes, love and life must happen, even at wartimes. War doesn’t kill feelings, lust or emotions. So, we see Lieutenant Kanu Ofodile (trainer of special constables) making overtures towards Ginika, we see Eloka and Ginika falling in-love and marrying eventually, we also see Sergeant Sule Ibrahim being so enamoured by Ginika that he goes to circumcise himself and dies in the attempt in order to win Ginika’s love. Also we see reckless living among soldiers and civilians alike.

Weaknesses of the novel

For me, a major weakness of the novel is in its delayed take-off into the main story of how war meets ordinary people and disrupts their well laid-out plans.

Sluggish and repetitive language use in some places also mars the beginning. For example, note the repetitive use of she in the following sentences: “She ran a comb through her hair and, pulling it back held it with a black band. She wore a pale green dress. She had decided that it was going to be dark colour henceforth since…She felt that bright colours… She looked forward to joining Eloka…She resolved not to allow the fear of air raids…” – all these /she, she/ occur in one paragraph concurrently.

It could have read: “Ginika combed her hair in front of the mirror and scrutinized the fitted green dress she was wearing. She had decided that no more bright coloured dresses for her since after she was nearly killed in an air raid at the market the other day. The thought of Eloka filled her mind. Would he like the dress? She would soon be joining him for…”

The intro appears slow also because the reader is not privy to Dr Ubaka’s lack of respect for boundaries and the opinions of others. Personally, I consider Ginika’s unwillingness to follow her father from Enugu to Mbano in the intro, not paunchy enough. For me, if the author had sneaked in some ruminations of Ginika concerning the breaches of father/daughter boundaries her father is guilty of or his obduracy, the reader would have been drawn into the story from the beginning. Because of these ‘faults’, the reader’s (or at least mine) interest wasn’t engaged from the onset. Intros must engage a reader.

Deeper into the book, the reader sees Ginika’s father’s overt strictness and the scene after the Ugiri dance when he actually inserts his fingers into his daughter’s secrets to check if she’s still a virgin! Here, the reader begins to appreciate the young woman’s aversion to her father.

Another weakness for me is the choice of names. They are a bit difficult to pronounce even for an Igbo person.

So take off for the novel isn’t fast and smooth due to sluggish repetitive diction. Diction drags, not fast-paced.

Strengths of the novel

Nevertheless kudos to the author, although diction struggles but it rises into the airspace and gradually begins to glide and then cruise. It goes fast as the reader reaches about the 17th chapter, entering into that airspace that is curious, suspenseful and nerve-racking, where the reader can no longer put down the novel to sleep.

From here, the reader wants to know what happens next. And it stays on this altitude till the end, becoming exciting moving fast from one interesting scene to another, springing up surprises like Ginika marries Eloka, Eloka joins the army despite his parents’ pathetic aversion to the army especially towards their son joining since he’s an only son.

Ginika starts work at a refugee camp, finds out about her father-in-law’s mistress. Her mother-in-law harasses her about being pregnant, mother in-law beats up mistress, people dying in the camp like chickens, Eloka returns for three days, mother-in-law wants to know if Ginika is pregnant, learns she’s not and gets offended, asks her if she’s ignorant of why they married her. She promises to give Ginika hell.

Ozioma, Eloka’s sister leaves the scene to do omugo instead of her mother; mother-in-law finds opportunity to fulfill her promise to give Ginika hell. She heaps on her all the house chores withdrawing her helps. This state of affairs drives Ginika to attend a phantom dance with a co-refugee-camp worker, Janet at Nkwerre. Ginika gets drugged, raped and falls pregnant!

And like a nightmare she can’t set things right. She gets thrown out of her in-law’s house, loses her job, has a stillborn and goes to afia attack!

Roses and Bullets catches fire the moment Ginika goes to Ama Oyi and the fire rages to the end drawing us into the war, wrenching our hearts. Sometimes, making us cry, fear, frustrated, laugh, glad, etc.

Strong messages are passed in Roses and Bullets. Apart from the different love issues, the author touches subtly the issue of sexuality which is the rage in our world today. Philomena, Ginika’s friend sleeps over in her house and in the middle of the night, rolls over and kisses and fondles Ginika!

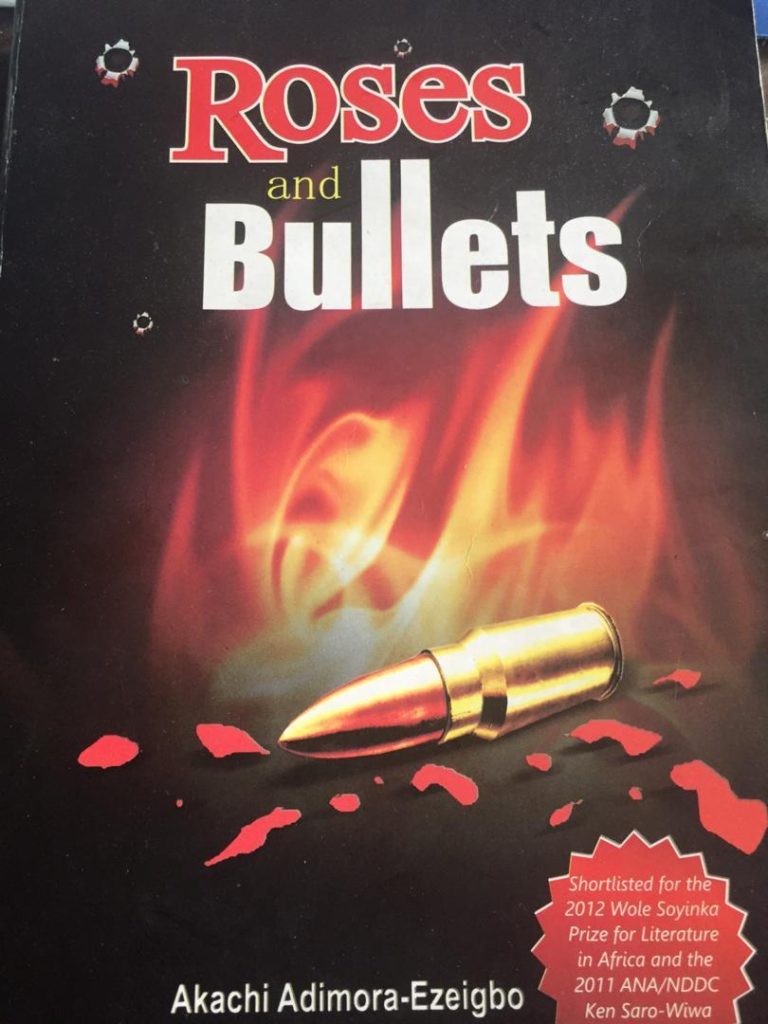

.Review for Roses and Bullets, a war novel by Akachi Adimora Ezeigbo continues next week