By Kelechi Mgboji

Nigeria has overtaken South Africa as the continent’s largest economy, but it will trail South Africa for decades in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which was $2,860 in 2013, against $6,950 in South Africa, according to emerging market economist at Standard Bank, London, Samir Gadio.

GDP per capita measures the earning power and wellbeing of citizens.

In an email obtained by TheNiche, Gadio noted that “electricity generation is MW4,000 in Nigeria at best compared with MW40,000 in South Africa. South Africa has institutional capacity and sophisticated financial market.”

Nigeria’s economy, rebased to $510 billion gross domestic product (GDP) to become the 24th largest economy in the world, does not reflect the macroeconomic reality that most citizens merely exist without basic social facilities.

The country is now said to be ahead of South Africa, which has $350 billion GDP.

Nigeria was ranked 36th in 2012.

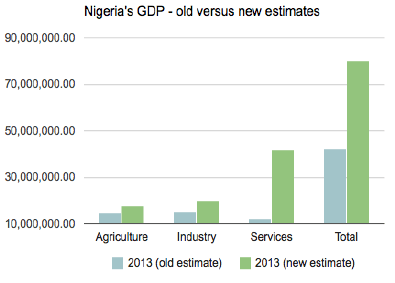

After a lengthy rebasing of economic data to include sectors such as telecommunications, e-commerce and the music/film industry, the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced that GDP for 2013 rose 89 per cent, from N42.3 billion to N80.22 trillion ($509.9 billion).

This places Nigeria among middle income countries, at par with Poland and Belgium, and ahead of Argentina, Austria and Iran.

The $1,200 by which Nigeria’s per capita income has suddenly risen has not translated to economic improvement on the ground. Per capita income at $3,000 is still low – and less than half South Africa’s $7,336.

The sprawling class of ‘bottom millions’ condemned to extreme poverty by bad policies will continue to struggle with poverty, inequality and shortage of amenities.

Even in the days of oil boom, the wealth of Nigeria was not evenly distributed; the poverty rate was high. There existed, and still exists, a huge shortfall in all areas of infrastructure: water, electricity, housing, education, roads.

This explains why the concept of economic growth in the country is controversial.

Statistics from 1988 to 1997 show a 4 per cent growth after the negative growth of the early 1980s.

In the 1960s, agriculture contributed at least 53 per cent to GDP but declined to about 34 per cent by 1998 due to the neglect of the sector in favour of oil.

In recent times, the government claimed the growth rate of the economy was between 6.5 per cent and 7.6 per cent and unemployment 23.9 per cent.

The 2014 budget assumed about 7 per cent economic growth as well as investment in infrastructure and diversification from oil into other sectors, particularly agriculture.

Prior to the revision of the GDP, the growth rate between 2010 and 2013 was believed to have declined, as it had in previous years.

The July-August edition of the Global Finance Magazine reported that in 2010 Nigeria’s GDP was 32.8 per cent, but trimmed down to 7.2 per cent in 2011 and 7.1 per cent in 2012.

The figures, which the magazine claimed to have obtained from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), also show that unemployment in 2011 was 23.9 per cent and inflation 11.2 per cent, against 10.8 per cent in 2010.

Yemi Kale, head of the NBS, acknowledged that the latest GDP figure “though depicts how rich a nation is, this is not necessarily the same as showing how rich the individuals in the nation are, due to the problem of unequal distribution of wealth. Similarly, growth in GDP is not synonymous with job creation.

“It is expected that as the economy grows, people’s income rises and their demand for goods and services increases. As a result, producers increase output and employ more people so that employment increases.

“However, though jobs are being created, the jobs may not be enough to reduce unemployment or poverty.”

Nevertheless, Finance Minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said the change would have a “psychological impact” on foreign investors who would pay more attention to Nigeria now that its economy is larger than that of South Africa.

“Business will also boom for hotel owners, travel agents, airlines, and events planners as the number of Nigeria-focused trips and investment conferences (already a booming industry since 2013) swell,” she enthused.

But Razia Khan, Africa Research head at Standard Chartered Bank, reiterated that “Nigeria’s single commodity dependence is a long-running problem, which tends to get less focus in good times, compared with bad times.”