On Biafra and Kanayo Esinulo’s Ojukwu memoirs

By Missang Oyongha

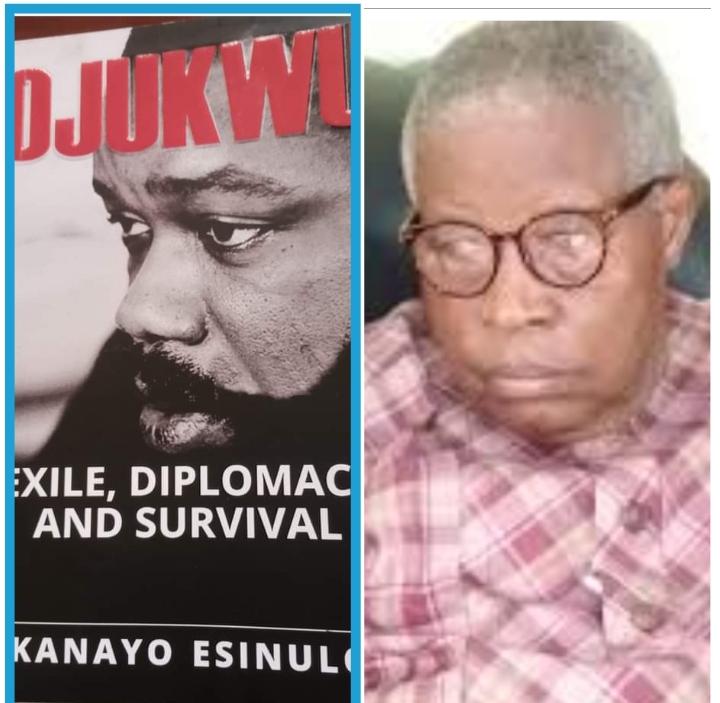

On August 29, 1970 the New York Times published a report by its Nigeria correspondent, William Borders. It was about the life in exile of the Biafran secessionist leader, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu. Seven months earlier, in January 1970, Ojukwu had arrived in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, aboard a Fokker Friendship Air Gabon plane from Libreville. Ivory Coast, along with Gabon, Tanzania and Zambia, had been one of the only four African nations to grant diplomatic recognition to Biafra. Borders’ report noted that Ojukwu had been accompanied by a large assortment of relatives, select officials of the Biafran High Command and cadres of his lost cause, but that “much of the rebel leader’s entourage (had) drifted away.” The historian Kenneth Dike had taken up a professorship at Harvard; but military commander Alexander Madiebo and diplomat Peter Ochigbo remained in Ivory Coast. President Felix Houphouet-Boigny declared that ‘Ojukwu, although entirely free in his movements, will have no political activity in Ivory Coast.’ The Ivorian government, or its President actually, gave Ojukwu the run of an ornate estate in Yamoussoukro. In principle Ojukwu kept faith with the terms of his asylum, granting no press interviews and making no declarations. Unwilling to resign himself to table tennis and reminiscence, however, he maintained discreet contact with allies in Nigeria, Ghana and elsewhere, helped by a select group of cadres and close associates. One of the close associates who remained by the leader’s side during his twelve-year exile, his private secretary Kanayo Esinulo, has just published a memoir about that fateful period, Ojukwu: Exile, Diplomacy and Survival.

Esinulo’s memoir has all the virtues of history as written by an eyewitness who was a participant as well as a victim. His is a shrewd, scrupulous narrative, eschewing speculation and innuendo in favour of straightforward reportage and matter-of-fact statement. Relying on the reader’s foreknowledge to fill in the historical preamble, Esinulo’s story focuses unwaveringly on the drama of life in exile, not on rehearsing the horrors of Biafra. Much has been written already about that tumultuous 30-month episode; and more will undoubtedly be written, but Esinulo’s book is certain to elicit, in the stream of an informed reader’s consciousness, concentric circles of thought. Like all traumatic historical events, Biafra has accreted about itself, in a process which continues apace, a body of historical records, academic studies, novelistic fiction and outright apocrypha. For a single individual to do justice to this subject in one volume would require great fortitude, the cerebral heft of a committee and a certain omniscience. Biafra was a Nigerian theatre of war, but it was also a theatre of Western realpolitik. On January 14, 1970, when Ojukwu was still in Libreville, the CIA sent a classified telegram to the Nixon White House reporting on the travel arrangements of Christopher Onyekwelu, C. C. Mojekwu and Jacques Foccart, the latter the French Secretary-General for African and Malagasy Affairs. All three men were flying from Europe to meet Ojukwu in Libreville. Although the French had been major suppliers of humanitarian relief and light war materiel to Biafra, the CIA telegram quotes Jean Mauricheau-Beaupre, Foccart’s deputy, as admitting that “France supported Biafra because of the oil and ERAP, but not the Ibo revolution.” When President Nixon was visiting Europe in 1969, the State Department briefing paper he received advised him to make clear to Prime Minister Harold Wilson that a Federal victory over the Biafrans would be ‘in (America’s) best interest,’ although the official US position had been one of studied neutrality. During a three-hour long parliamentary debate on the supply of arms to Nigeria, held on June 12, 1968, the British MP Sir John Eden decried the perfidy of Her Majesty’s Government organising peace talks between the warring factions while supplying arms to the Nigerian government. The British government was neither willing to countenance the amputation of Nigeria, as a geopolitical prize, nor risk any injury to the petroleum interests of Shell-BP. The USSR supplied a steady stream of MIG and Ilyushin bomber jets to the Federal side, hoping to make a strategic impression on this portion of the chequerboard. (When Aleksandr Romanov, Soviet Ambassador in Lagos, ended his six-year tour of duty in October 1970, General Gowon presented him with the Commander of the Order of the Niger). Felix Houphouet-Boigny, Ojukwu’s host and the parental deity of Ivory Coast, was a fervent anti-communist. In Ivory Coast Ojukwu’s consigliere was the Frenchman, Colonel Fournier. The air was thick with intrigue. Ojukwu’s great friend Frederick Forsyth resigned from the BBC in 1968 when he discovered that the Foreign Office and the BBC actually expected him to file boosterish reports in favour of the Federal side. His bosses insisted that his reports from Biafra were not merely sympathetic but outright fictional.

How much closer does Esinulo’s book bring us to knowing the real Ojukwu? Various accounts of Ojukwu’s fateful life have been written, including by the man himself, but it is arguable that they offer us no more than the clothes and buttons of the man which Twain said constituted the unfinishable sketch known as biography. The US Ambassador in Lagos, Elbert Mathews, in an airgram to the State Department in 1968, described Ojukwu’s “panache, quick intelligence, and…actor’s voice and fluency.’ Jerome Udoji, the first African Assistant District Officer during British rule and Chief Secretary to the Government under Eastern Premier Michael Okpara, chafed under Ojukwu’s brusqueness and condescension when the thirty-three year old Lt-Colonel assumed office as Governor of the Eastern State in 1966. Udoji remarks in his memoirs (Under Three Masters) that Ojukwu had inherited none of his father’s ‘character’, or ‘down-to-earth lifestyle’ or ‘matter-of-fact‘ attitude. During that parliamentary debate in June 1968, the MP John Cordle had referred snidely to “the machinations of the public relations firms which have been retained by Colonel Ojukwu at fantastic expense,” obviously referring to the Geneva-based agency PR agency, Markpress. The war effort and his own Oxford-honed flair for the manufacturing of consent had impressed on Ojukwu the importance of a well-oiled press machine. Although the Biafran war was clearly a military campaign, the vast asymmetry between the two sides meant that for Ojukwu the war effort was as much for foreign public opinion as for domestic territory.

Although Esinulo’s memoir is ostensibly about a consequential political chapter in the history of Nigeria, it is also, at a subliminal level, a story about how individual agency and ambition can be overwhelmed and effaced by service to a cause, or to the charismatic embodiment of that cause. Mustafa Kemal, the charismatic Ataturk, told his Ottoman troops during the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915: “I am not ordering you to fight; I am ordering you to die.” Esinulo was never asked to die, but he did have to fight for his freedom and his life when, on a covert mission from Ivory Coast on behalf of Ojukwu in 1973, he is betrayed in Lagos, arrested and detained without trial at the Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison, Nigeria’s premier hellhole. He develops a chronic hip fracture. Henchmen of the regime accuse Esinulo of being a courier for Ojukwu, and of being a vendor of propaganda against Gowon. The two-year fight for his release is led by the redoubtable Gani Fawehinmi, the book’s dedicatee. Esinulo’s cause was also taken up by Amnesty International, as well as Olu Onagoruwa, Wole Soyinka, Tai Solarin and Ojukwu himself. Readers who, like me, have a taste for non-fictional cloak-and-dagger narratives will find much to savour in Esinulo’s book. After his fortuitous release from Kirikiri Prison, Esinulo is spirited away from Lagos to Cotonou in a pre-dawn operation led by an unnamed Frenchman in a car with diplomatic plates, whom we can surmise was part of the long-armed network of European agents and fixers that had coalesced around Ojukwu in his Biafran heydey and in his Ivorian exile. Ojukwu is said to have relished his given name, ‘Emeka,’ but in exile he went by several secret aliases, known only to initiates like Esinulo, who would typically telephone to leave coded messages for Christophe Onikel or Dr Kofi. Although Ojukwu was generous in arranging a scholarship for Esinulo to study at Erasmus University in The Hague, later on, when Esinulo is accepted to a Swedish university to study for a doctorate in sociology, Ojukwu vetoes the idea on the grounds that a far more important task is the one of ending his exile and returning to Nigeria.

READ ALSO: Chris Anyanwu’s Bold Leap

The exile is haunted by visions of a return to his homeland, even if, as in the case of Ojukwu, he had violently renounced citizenship and belonging. Memory is not so easily renounced. John de St Jorre wrote in 1972 that in being deprived of a state, a people, a platform and a stage – the very lifeblood of an oratorical leader and actor – exile would prove to be ‘a living death’ for Ojukwu. Esinulo records an Ojukwu who was racked with guilt over the fact that before events compelled him to declare secession he had glibly encouraged Igbos who had fled pogroms in the North to return there, only for them to be mercilessly butchered, in spite of the personal assurances of Lt-Col Hassan Katsina, Governor of the Northern Region. Biafran war arguments have often turned on the intentionalist question of whether Ojukwu wanted secession all along and the functional question of whether he was compelled to act by the sheer weight of Eastern blood spilt in the North, and by Federal complicity or inertia, or by Federal bad faith after the agreements of Aburi. Secession had in any case long been a trope of political brinkmanship in Nigerian politics, since the Ibadan Conference of 1950 where the Emirs of Katsina and Zaria had threatened that Northern Nigeria would secede if it were not allotted half of the seats in parliament. Jerome Udoji argues in his memoirs that the Biafran war might have been averted if the military Governor of Eastern Nigeria had been a man less convinced of his own world-historical singularity, less intoxicated by his own intellect and less committed to ‘bluff and brinkmanship.’ Philip Effiong’s capitulatory Radio Biafra broadcast of January 12, 1970, contained the accusing line about the voluntary departure of ‘elements of the old regime who had made negotiation and reconciliation impossible.’ A CIA memo from May 29, 1969 noted that ‘Ojukwu’s style of governing is highly personal, but he does rely on advice from a number of close associates.’ The names of Christopher Onyekwelu and C. C. Mojekwu recur; their roles, as kinsmen, counsellors and arms buyers, were crucial to the war effort.

”My role can only be moral,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn told an American journalist in Vermont as he prepared to return to Russia after twenty years in exile. The political permafrost had thawed beyond recognition, and the streets of Moscow were awash with Western consumer culture, the previous object of official contempt. Those implacable Kremlin foes of Solzhenitsyn’s, Brezhnev and Andropov, had succumbed to death, Gorbachev and Yeltsin. For Ojukwu there had never been any doubt that he would return to Nigeria, and be Nigerian again, but he envisaged for himself a role which would not only be moral. In Nigeria too the political situation in 1982 was different from that of the country Ojukwu had fled twelve years earlier. Although the country still seemed to be the ‘mutual non-admiration society’ described by Anthony Kirk-Greene, dean of British Nigerianists, Nigeria’s elected Vice President was an Igbo man from Ojukwu’s Anambra State. Esinulo’s book recounts in compelling detail the intricate round of back-channel meetings, lobbying and communications which prepared the way for Ojukwu’s return from exile in June 1982. Accompanied by a camera crew from his day job at the Nigerian Television Authority, Esinulo inveigled his way into Chuba Okadigbo’s office to deliver the opening gambit, a secret message from Ojukwu. From there followed clandestine meetings with NPN grandees Ibrahim Tahir and Victor Masi. Yet I was struck by the unyielding cadences, the rhetorical brinkmanship of Ojukwu’s memo to Esinulo in 1981: ‘For my homecoming to have any real meaning it must be devoid of restraints. I seek no pardon for I have wronged none. I seek no amnesty since I committed no crime. I seek no clemency because I have not been judged.’ Politics, no less than human endeavour in general, is often an unstable, intriguing compound of perceptions, motives, circumstances and egos. Chuba Okadigbo, whose influence as Political Adviser to President Shagari had been pivotal to the process of shepherding Ojukwu’s return, made it clear to Esinulo that he wanted to take sole credit for the momentous turn of events, ostensibly because his bete-noire Vice President Alex Ekwueme also stood to make political capital from the triumph. When the pardon was issued, Okadigbo flew out to Bingerville to deliver the news in person to Ojukwu. Regarding the motivations of Shagari himself in granting an unconditional pardon, Ojukwu surmised that the President was driven by the desire to secure a historical pedestal as the man who ‘closed the chapter on a painful national episode.’ A more prosaic motive could have been the need for Shagari’s NPN to bolster its support among Ojukwu’s fellow Igbos in the 1983 elections. In 1981 Ojukwu had been outraged to learn that his erstwhile nemesis turned fellow political exile, Yakubu Gowon, would receive a pardon which enabled him to return from six years in London. Jerome Udoji saw only ‘opportunism’ in Ojukwu’s own decision, as soon as he was Nigerian again, to leap on the soapbox and vie for a Senate seat, inverting the Clausewitzian formula about war being the continuation of politics.

After Ojukwu’s return to Nigeria, Esinulo finds that contact between him and the leader becomes ever more strained and tenuous, the intervals between meetings lengthier. There are no more coded messages for Christophe Onikel and Dr Kofi, who has by now been christened Ikemba Nnewi. There are no more lengthy memos from mentor to protege on the political situation in Nigeria and the place of the Igbos within it. Esinulo writes that Ojukwu’s decision to join the ruling National Party of Nigeria was not accepted by many of his associates, but that they found themselves unable to ‘forcefully oppose’ their leader about this. Political figures have a certain ability to compartmentalize past relationships and present exigencies without remorse and without sentimentality: “I am not asking you to fight. I am asking you to die.”

In an illuminating 1989 essay, the historian Tekena Tamuno raised the question of what exactly Nigeria had salvaged from the war, other than territorial integrity. After January 1970, Nigeria had become wholly Nigerian again, but the morbid symptoms of its recent fever remained: tribal tensions, official corruption, military coups, a maniacal dependence on oil revenue, accompanied by inequitable distribution of those same revenues. Keynes, in The Economic Consequences of the Peace, wrote about the ‘hidden psychic and economic bonds’ between the victorious Allied powers and the prostrate German and Austro-Hungarian empires, bonds that he thought made a humane Treaty of Versailles necessary, rather than the ‘Carthaginian’ terms that Georges Clemenceau, especially, seemed bent on inflicting. A CIA memo from January 29, 1969 included the chilling line that ‘at least some Nigerians favor starving the Biafrans into submission as the best war policy.’ There are those who insist to this day that Finance Minister Obafemi Awolowo was pursuing a Carthaginian policy when he decreed the payment of only twenty Nigerian pounds to all former Biafrans who had held accounts in Nigerian banks; a view reinforced when he went on to ban the import of dried cod and used clothing, economic activities in which Eastern Nigerians/former Biafrans had been dominant. Yet, in that memorable photograph from January 14, 1970, General Gowon and Biafran Chief Justice Louis Mbanefo embraced at Dodan Barracks, while General Philip Effiong, who had bonded with Gowon at Sandhurst, looked on in relieved amusement. Through Bola Ige, General Gowon sent a cold apologia to the most famous prisoner of the war, Wole Soyinka: “Bygones is bygones.” The war had been won and lost, and it was time to live with the consequences of the peace.

- Missang Oyongha is the Literary Editor of MMG. This review essay reflects his personal views. He can be reached via email: missang.oyongha@gmail.com