Ogoni Nine: HOMEF documentary reveals anguish of dependents left behind 30 years after judicial murder

By Ishaya Ibrahim

A new documentary from the Health of the Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF), marking the 30th anniversary of the judicial murder of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni activists, known as the Ogoni Nine, reveals the disturbing anguish and long-term struggle of their dependents.

The activists were executed on November 10, 1995, by the government of the former Head of State, General Sani Abacha. Among the slain were Ken Saro-Wiwa, Saturday Dobee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbooko, Paul Levera, Felix Nuate, Baribor Bera, Barinem Kiobel, and John Kpuine.

The film, shown on Thursday to journalists during a media parley in Lagos, featured an emotional interview with Eawo’s widow, Blessing Eawo, who is currently blind. The relentless tears she shed after being left with five starving children to cater for led to her blindness.

“I used to farm, but in the last 25 years, I couldn’t because I lost my sight. I had to beg to feed my five children. It is the Christ Army Church that has been helping me,” she revealed.

Another survivor, Kabari Nuate, son of Felix Nuate, said he was five when his father was killed, abruptly ending his educational pursuit as there was no one to foot the bill.

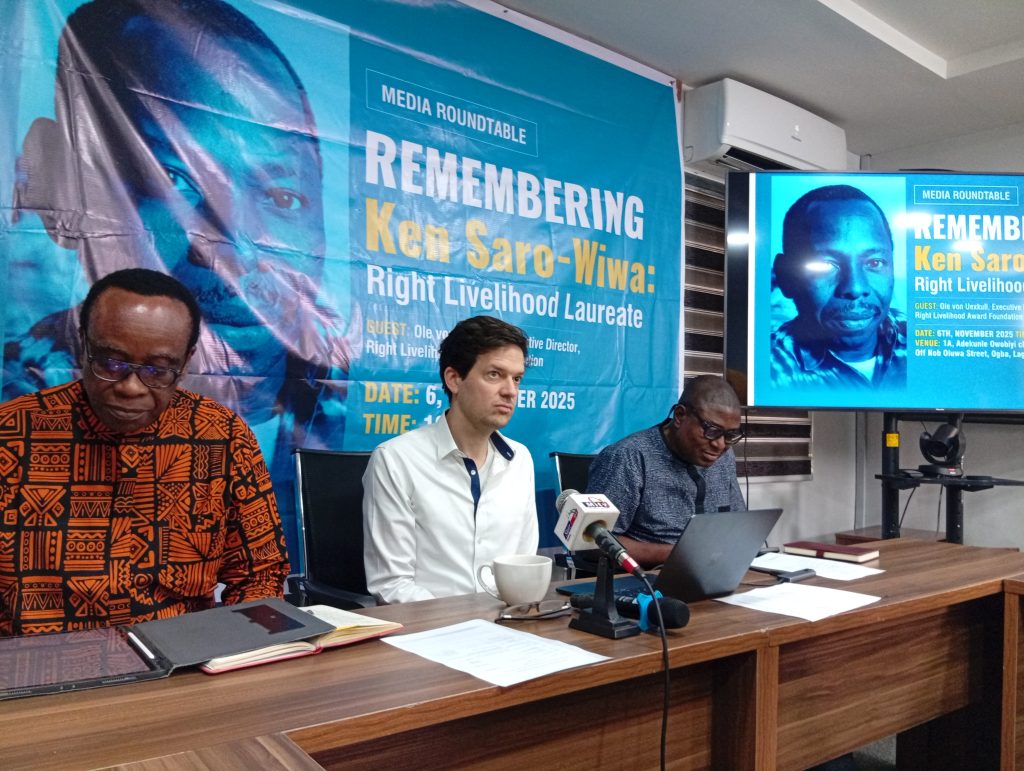

Ole von Uexkull, Executive Director, Right Livelihood Award Foundation (Alternative Nobel Prize), recalled how in 1994, Saro-Wiwa received the award for environmental protection while in prison based on his efforts in protecting the environment of his people.

He said of Saro-Wiwa: “He was just working for the interest of his community and the people around him to live dignified lives, which was being destroyed by Shell and the companies. At the time, in 1994, when he received the award, he and the others were already in prison.”

He quotes from the acceptance speech Saro-Wiwa sent from prison: “The inconveniences which I and the Ogoni suffer, the harassment, arrests, detention, and even death itself, are a proper price to pay for ending the nightmare of millions of people.”

Ole von Uexkull said Saro-Wiwa’s struggle to create a better environment for his people aligned with the motivation of his uncle, Jakob von Uexküll, to institute the award after trying to convince the Nobel Prize organisers to add a category for environmental justice.

He explained: “This was an initiative by my uncle in 1980. So we are already in our 46th year this year. We now have 200 laureates from around the world. But his idea in the late 70s was to say, ‘Why is there no Nobel Prize for the environment and for the concerns of poor people in the world?’ And he offered some of his own money. He was not as rich as Nobel had been, but he offered his own money to the Nobel Foundation and said, ‘Why don’t you create these two new categories of awards?’ And they said, no, no, no, we don’t want any new awards.”

When Saro-Wiwa was killed, he recalled how his uncle reacted: “I was 17 at the time, and because it was my uncle who started the organisation, I remember him in frantic calls with all the other international supporters because there was a big commotion.”

He added: “And then I remember receiving the news, and I was in a city in Germany, in Hamburg at the time, where the Shell headquarters for Germany is. And so we were a small group of people protesting the next morning outside this Shell headquarters. I just remember the shock at seeing, I mean, we were there at the gates in the morning, and people working at Shell were just passing by as if nothing had happened.”

He said 30 years after the murder of the Ogoni Nine, things haven’t improved. “We’re now having to fight plans for a reopening of oil drilling in the area, which seems absolutely crazy given the history, especially as the world at large is moving away from fossil fuels and moving to renewables.”

HOMEF Executive Director, who also is 2010 recipient of the Right Livelihood Award Foundation, Dr. Nnimmo Bassey, said Saro-Wiwa and the other Ogoni activists paid the supreme sacrifice in the fight for self-determination, justice, dignity, and respect for the Ogoni.

Citing personal connection, Dr. Bassey said: “I knew him as a writer, as an activist, and he was more than that. He was a businessman, a politician, an educator, a playwright, and a publisher. He really believed in the liberation of his people, and if you want to point out one individual who transformed the narrative concerning his people, I think Ken Saro-Wiwa would be in the top range. He has really changed that narrative.”

He said Saro-Wiwa would have been 84 years old now, but the government of the day, working with their partner, Shell, took his life, totally against the rules of the tribunal that tried him. “They had 30 days for appeal after the judgment was declared, but he was killed within just a few days after the judgment. They didn’t even give him a chance to appeal.

“The whole world, the United Nations, international organisations, the Commonwealth, was having a meeting in Australia on the day he was killed. In fact, a delegation was to be sent to Nigeria to talk to the government, and Nelson Mandela was to lead that delegation. But before they could even leave to come, they had rushed to hang them,” Dr. Bassey recalled.

He said the motive was a deliberate effort to silence dissent, to silence the people of Ogoni and, by extension, anyone else in Nigeria who would speak against reckless extraction.

He said Saro-Wiwa was clearly a shining light who preached and practised peaceful advocacy. “He was a man of peace; he was peaceful, he didn’t want anyone’s blood to be shed.”

Dr. Bassey added: “He was a peaceful militant organiser. In other words, he wasn’t going to back down just because you pointed a gun at him. Even while he was in prison, he was writing, and you have the book of his last writings called Silence Will Be Treason.”

He lamented that 30 years after the murder of Saro-Wiwa, the Ogoni Bill of Rights that was given to the government of Babangida in 1990 is yet to be addressed.

According to Dr. Bassey, even after the flag-off of the cleanup of Ogoniland, an area devastated by pollution, no spill was ever cleaned up the way it ought to be cleaned up.

He explained: “The UNEP report showed that pollution at Ogoni in some places was five meters into the ground, and by the time the place was excavated, it had gone as deep as 10 meters. So the more you leave pollution, the deeper it sinks, and it doesn’t disappear.”

He added: “People are growing crops in polluted land, people are fishing in polluted water. I’ve seen fisher folk in Ogoniland. There’s one man I saw some years ago, and he just came back from fishing. His legs and feet were covered with crude oil. The plastic he carried, the fish that he caught, were covered in crude oil. So I asked him how much was the fish. So he told me the price, I bought all the fish. I wasn’t going to eat them, but when I say all the fish, the fish could not even cover the bottom of the plastic container. It was just a few pieces. And then I asked him to open the fish. When he opened it, there was oil inside, not blood; you could see oil inside the fish.

“So, people are really living in a poisonous, toxic environment, and now for the government to think nothing of cleaning up the entire Niger Delta, but is going ahead to keep on polluting it. They talk about increasing the production of oil in Nigeria to three million barrels by 2030. I mean, this is like putting a finger in the wound of the people to say, ‘Look, it doesn’t matter what you are saying, we’re going to get what we want.’”

Akinbode Oluwafemi, Executive Director, Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA), said the killing of the Ogoni Nine came as a rude shock to the world because the consensus was that even a mad person wouldn’t do that. “We read from student activism, and the whole world was like, no madman will do that. But we didn’t know that Abacha was madder than we thought.”

He is however consoled by the fact that the memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa lives on.