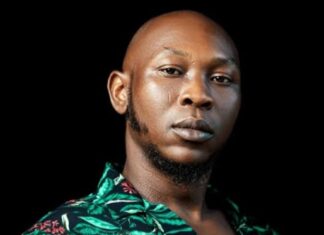

A young boy from a middle-class home gets an unconventional schooling in the ways of the world when he’s forced to apprentice at a mechanic’s workshop in a rough-and-tumble section of Lagos. “Mokalik” is the latest feature from Kunle Afolayan, a leading figure in the wave of filmmakers revitalizing the Nigerian film industry. The film is screening this week at the Durban Intl. Film Festival.

Afolayan spoke with Variety about the chancing face of Nigerian cinema, the impact of Netflix on African filmmaking, and why more international players need to come to the table to recognize the continent’s untapped potential.More from Variety

- Locations Africa Expo Sends Message in Durban: ‘Africa is Ready’

- Report Urges South African Media to ‘Step Up’ Against Gender Violence

- Realness, EAVE, IFFR, Sundance Launch African Producers Network

You’ve experimented with a range of genres and themes across your career, from the supernatural drama “The Figurine” to the romantic comedy “Phone Swap” to the historical thriller “October 1.” “Mokalik,” on the other hand, was inspired by an actual day in your life. What made you want to dig into your own personal experience with this film?

Sometimes we evolve in an environment where you haven’t paid a lot of attention to things that go on around you. I hadn’t been to a mechanic workshop in a long time. And at that time, I wanted to properly restore a vintage car—that’s what took me there. I ended up spending a week, going every day. Every time I was there, I saw different things, their way of life. Most of them are not university graduates. But somehow, they train on the job, and they’re getting things done. I thought it would be nice to tell their stories from a different point of view.

When you started making movies, you were among the first of the current generation of Nigerian filmmakers with bigger aspirations for an industry that was long known for its roughshod, straight-to-DVD releases. Your films had bigger budgets and were made for the big screen. Now, there are roughly 20-30 theatrical releases in Nigeria every year, with production values and budgets both rising. How would you rate the progress of the Nigerian industry in 2019?

I think it’s more dynamic now, it’s more interesting. A lot of people now see the need to pay more attention to details. The cinema chain has grown from what it was a few years back, and it’s still growing. I know quite a number of people who are currently building more screens. I think the business side is very good. There seems to be return on investment. Beyond that, the number of productions has reduced, but it’s better now in terms of quality and production values. Some people are just going for the commercial. “We put good money in a film, it’s going to be all glamorous and bling. We just want to do a cinema run, and maybe, if we’re able to get Netflix, fine.” They’re not really interested in seeing film as art. To them, it’s about, “What are we grossing?” As soon as they’re done doing this, they move to the next one.

We still have the likes of myself and other filmmakers who say, “Look, you can be commercial and still be arty to a certain extent.” Because you want to go to festivals, you want these films also to be written about, to be talked about, and still enjoy the commercial platform. We have a lot more of the commercial films now. They’re doing their route, and they’re making money. I think that’s really good for the system.

Nigerian filmmakers have always gotten a lot of support from their audiences. Do you think the industry gets enough support from the government, and from private equity, for it to reach a higher level?

In terms of government support, to an extent, I would say government is trying. Recently the federal government through the central bank introduced another loan scheme. You can get a loan to build a cinema, or to make a film, and the interest rate is a quarter of what you get in commercial banks. And the flexibility is better. You can pay within 10 years. No commercial bank would ever give you that. That’s one aspect of support. Also, the Lagos State Government just commissioned six theaters that would double our cinemas [in Nigeria’s largest city], and four of them have been completed. This will also help the monetization of content. In those areas, our government seems to be doing well.

If you compare Nigeria to a lot of other African countries, I think we’re way ahead. A lot of other African countries look up to Nigeria. They also want to emulate our spirit and our attempt in terms of monetizing content. I would say we’re not doing badly. Government is supportive, and I think they’re trying to understand how to put the best structure that would help develop the industry more.

Netflix acquired “Mokalik,” and a number of your other films, earlier this month, and has been growing its Nigerian library for several years. You’ve certainly screened many of your films internationally, but do you feel like there’s something missing in the value chain for you as a Nigerian filmmaker, when it comes to reaching global audiences? How big of a game changer are the streaming services for the industry?

I think it’s still a struggle, when it comes to getting international reach and recognition. But [the streaming services are] a good thing. In 2014, “October 1” was the first film from Nigeria that Netflix acquired. I’ve had meetings with them, and we’re looking beyond the films that I’ve made. We’re also looking at original content. This is just going to be the start of something new.

A lot of Nigerians, Africans in the diaspora—the majority of them are on Netflix. This will allow them to actually see how far we can be going in terms of quality. I think the perception out there is wrong

[about Nigerian films]

. I think a lot of audience will also see the variety of Nigerian films that are now getting on Netflix. Yes, we will still try to do cinema runs and also try to do other distribution platforms. But Netflix is so global. For me, it’s the beginning of the better things to come from Africa and Nigeria.

Netflix and other streaming services obviously give Nigerian filmmakers the chance to reach global audiences, but is it a fair trade-off when you’re signing away your world rights? Many African filmmakers feel that the streamers undervalue African content, and because of that sliding scale, it doesn’t necessarily make financial sense to give them worldwide SVOD exclusivity.

I don’t think it’s a level playground. For one, Africa is still being seen as a developing market in terms of film and television. Because they’re trying to grow, whatever they’re offering for film must be justified by what comes back to them. I will clearly say at this point, there is no comparison between what they offer for content from here, and what they offer for content in Europe and America. Because they always say that they’re trying to build the African market.

I think Netflix is the only one that is at the moment really trying to embrace Nigeria and the rest of Africa, more than the rest of these platforms. But I want to believe it’s going to get there at some point. I have a series I’ve been developing for three years that I believe will take African film and television to another level—level of “Game of Thrones.” It’s very original and very big. I believe anybody who would take chances on that would not regret it. I think they all need to be more open now. [Africa] is such a big market. But these are stories with universal appeal that would do well anywhere in the world. They should not see Africa as a second- or third-class audience. I think that needs to change.