With the Supreme Court judgement, the era of uncertainty on the status of the local government system, can safely be said to be over. The days ahead promise to be exciting as legal and constitutional experts offer more explanations on the import of the judgement.

By Emeka Alex Duru

Editor

The landmark judgement by the Supreme Court, on Thursday, July 11, 2024, which grants financial autonomy to the local government areas, has brought to a refreshing end the servile status assigned to that otherwise, critical segment of the government by the state governors. With the new development, the councils are expected to assume their full role as the closest tier of the government to the people.

The Supreme Court in its judgement, declared that it is unconstitutional for state governors to hold funds allocated for local government administrations. The court further declared that a state government has no power to appoint a caretaker committee, stressing that a local government council is only recognisable with a democratically elected government.

The seven-man panel, in the judgment delivered by Justice Emmanuel Agim, declared that the 774 local government councils in the country should manage their funds themselves.

The apex court held that the power of the government is portioned into three arms of government, the federal, the state and the local government. It ruled that state governments are perpetuating a dangerous trend by refusing to allow democratically elected local government councils to function, instead appointing their loyalists who can only be removed by them.

“A democratically elected local government is sacrosanct and non-negotiable,” the court said.

The judgement is a fallout of a suit filed by the Attorney General of the Federation, Lateef Fagbemi (SAN), on behalf of the Federal Government, seeking to grant full autonomy and direct funding to all 774 local government councils in the country.

In response, the 36 state governments, through their attorneys general, filed a counterclaim, arguing that the Supreme Court lacked the jurisdiction to hear the case.

In Thursday’s ruling, Justice Agim affirmed that the AGF has the legal authority to initiate the lawsuit and uphold the constitution. Justice Agim said, “I hold that the plaintiff’s request is hereby approved and all the reliefs granted.”

READ ALSO:

Shehu Sani hails Supreme Court’s verdict, says it freed LGs from decades of captivity

The judgement has restored the integrity and importance of the local government system in delivering good governance to the people, experts say. Dr. Ogwanwa Rose-Confidence, a public administration expert, agrees with the verdict by the Supreme Court. According to her, the judgement has returned the local government areas to the intentions of the 1976 local government reforms that gave rise to the currently abused system. “The 1976 council reforms had intended to make the local government areas, the low-hanging fruits in terms of delivery of good governance to the people but over time, the agenda was abused and council was reduced to mere job for the boys. I am in support of the sound judgement by the Supreme Court”, she said.

In his opinion piece published in TheNiche newspapers, on June 14, 2024, titled; ‘Federalism, local government autonomy and the crisis of identity in Nigeria’, Austin Emaduku a public affairs analyst, had in part, observed that “Local government councils, counties, prefectures, cities, boroughs, municipalities, etc., the world over, are regarded as vehicles of grassroots development because of their closeness to the people. It is for this reason that it is often argued that they be granted enough financial strength and space to operate”.

He added however, that it is the question of municipal autonomy — the extent of autonomy that the councils should be granted — that remains a key question in public administration and governance the world over. That is precisely the argument that the Supreme Court has put to rest with the Thursday judgement.

Local Government Areas as underdogs

Framers of the 1979 and 1999 Constitutions who gave the Councils form, had fashioned the system to be the third leg in the decentralization of the governance process. The others are the Federal and State governments. With the Federal Government remotely distant from the electorate and the State almost overwhelmed by a multitude of functions, the Local Government was envisioned to relate to and cater for the people at the grassroots.

This, incidentally, is not the case. Reports from the councils rather indicate gross abuse of the system by both the Federal and State governments at various times. These abuses manifest in loss of autonomy by the councils as well as the tendency of denying them of funds. The most audacious assault on the system has been the undemocratic appointment of cronies by the governors to head the councils.

The future however looks bright for the system, going by the decision of the Supreme Court. Human rights activist and former federal lawmaker, Shehu Sani, enthused that by the judgement, the apex court has freed local governments from decades of captivity and systemic plunder by the States. That captures the mood of many.

Evolution of local government system

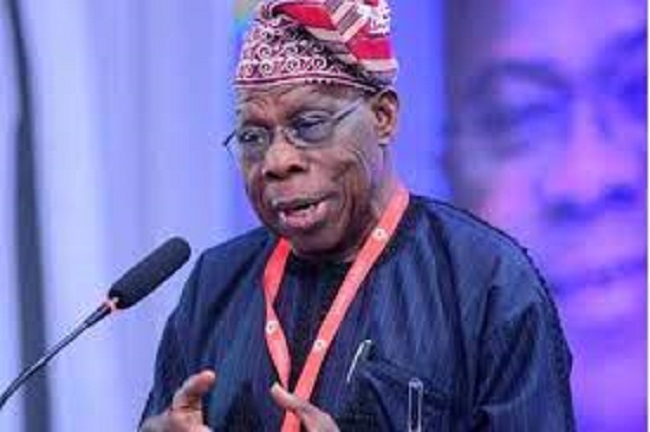

Local government administration, as it currently operates, is a product of the 1976 local government reforms. It was one of the fallouts of the then Generals Olusegun Obasanjo/Shehu Yar’Adua political transition agenda, aimed at transferring power to an elected civilian government in 1979.

Before then, council administration had existed in different guises. There had, for instance, been County Councils, Municipal Councils, Divisions or Native Authorities, depending on time and areas of operation.

In the North, before and shortly after Independence, Native Authorities and Emirate Councils carried out the functions of local governments. In the South, County Councils or Municipal councils were largely in vogue. Though various forms of elections were conducted to choose some members of the councils, many of them were chosen by appointment or by consensus by their respective constituencies. Chairmen of the councils were appointed by the government.

Members of the local governments assisted the government in collection of taxes or rates and other levies. They were also used in propagating the principles of governance to the people. For these reasons, traditional rulers and chiefs were co-opted in the councils. To encourage and reward them, they were allowed to keep a certain percentage of the revenue collected. With time however, corruption crept into the system. Council members not only appropriated the bulk of the revenue collected, they began to see themselves as tin gods. They became draconian, ordering the arrest and detention of perceived opponents on flimsy excuses.

Along the line, various forms of reforms were initiated and some actually implemented, to make the councils yield to the demands of the day.

A system derailed

With the incursion of the military into the nation’s politics in 1966, there was a heavy setback in the evolution of the councils. Though some miniature forms and structures of the system were tolerated, members were out rightly appointed and supervised by the state military administrators. Their tenure also depended on the mood of the governor.

Obasanjo-Yar’Adua to the rescue

That was the prevailing situation until 1976 when the Obasanjo-led military regime made case for the local councils to become a distinct tier of government.

Consequently elections were held in the council on non-party basis. On account of its success, the exercise was received all over the country with huge ululation. That formed the nucleus of what could be termed the modern system of local government administration.

The Constituent Assembly and the Constitution Drafting Committee between 1975 and 1978 debated the intention on the reform in details. Both efforts culminated in the inherent status in financing and functions of the local government as contained in the 1979 constitution.

In fact, section 7 (and subsection 2) of the 1979 constitution states that “the system of the local government by democratically elected local government councils, is under this constitution granted; and accordingly, the government of every state shall ensure their existence under a law which provides for the establishment, structure, composition, finance and functions of such councils”.

The 1999 constitution, also acknowledges the importance of the system in Section 7(1) where it, provides that: “The system of local government by democratically elected local government councils is under this constitution guaranteed; and accordingly, the government of every state shall, subject to section 8 of this constitution, ensure their existence under a law which provides for the establishment, structure, composition, finance and functions of such councils.”

Implicit in the 1976 reform was the desire to involve local citizens in the management of local affairs. There was also the need to ensure that basic needs of local citizens were speedily and efficiently met. It also provided a framework for effective mobilisation of human and material resources at the local level.

Perhaps, aware of the likely abuse of the spirit of the reform, it was fashioned in such a manner that the councils would have legal personality. Thus, they could sue or be sued.

They were equally imbued with specific powers with which to act. And they were envisaged to enjoy substantial autonomy especially in financial and staff matters, subject to limited control from the central government. With the government accepting the reforms, it created additional councils.

Democracy in the councils

In December of that year (1976), elections were held in the reformed councils on non-party basis. Similar exercise of electing council officials at specific time was to have been continued by the succeeding President Shehu Shagari civilian administration.

A system mismanaged

Ironically, the Shagari civilian administration which many had looked up to for consolidation of the gains of the 1976 council reforms, failed to conduct elections into the local governments.

In addition, the administration was accused of starving the councils of funds. This gravely impacted on their ability to carry out their constitutional functions. The government, also, for political reasons, created what later were regarded as “mushroom councils”, that were quite unable to sustain themselves. The councils thus depended heavily on the state governments for sustenance. The local governments were also frequently dissolved on flimsy excuses.

Autocracy in the councils

By December 31, 1983, the civilian government was sacked by the General Muhammadu Buhari (retired) military junta. The regime, shunning pretensions of any democratic credentials, went on with appointing sole administrators for the councils. It however abolished the councils created by the previous administration. Significant drawback of the sole administrator arrangement was that it was found lacking in transparency and accountability.

Revisiting the 1976 reforms

Following the ouster of the regime by another group of coup plotters led by retired General Ibrahim Babangida, an amended reform of the 1976 version was brought to bear on the councils.

Initially, the chairmen and other principal officers of the councils were appointed. But by Decree No 3 of 1991, it became mandatory for the council Chairmen, Vice Chairmen, Speakers of the councils and their councillors to be elected.

Babangida further upped the statutory allocation of the councils to 20 percent and directed that such funds should go directly to the councils as against the situation of channeling them through the states. The regime created additional councils, thus bringing the number to 589.

The apparent new lease of life infused into the local government system by the Babangida regime suffered a major setback with the succeeding late General Sani Abacha administration. The government jettisoned the idea of electing council officials and rather opted for caretaker committees as the supervising bodies for the councils. It, however, gave the country its current 774 local government structure.

Politicking with the councils

It was under the transition government of General Abdulsalami Abubakar that elections were again held on party basis to the local governments areas. The officials were elected in December 1998 but were sworn in May, 1999, clearly six months after. They were initially billed to stay for three years. But before their term elapsed in 2002, they had succeeded in getting the National Assembly to enact a law extending their tenure by one year. There was what many read as the unseen hands of the Presidency in the entire affair.

The suspicion was that the then President Olusegun Obasanjo, obviously uncomfortable with the attitude of some of the governors, had angled towards using the council officials, who would play significant role during the various party congresses, to get rid of perceived recalcitrant governors.

This allegation was not clinically proved. But whatever was the case, the governors did not want to take chances. They needed their re-election as did the president. And they needed the councils to be firmly under their control, by being allowed to appoint cronies who would be loyal, if not subservient, to them. Thus, they headed for the Supreme Court, challenging the elongation of the council tenure by the National Assembly. The governors obtained judgement in their favour, when the Supreme Court ruled on the matter on March 28, 2002.

Return of care taker committees

In what seemed to be a stop gap however, the governors floated the idea of appointing transition committees to oversee the affairs of the councils. The trend has sadly been maintained in some states.

The Supreme Court to the rescue

But with the Supreme Court judgement, the era of uncertainty on the status of the local government areas, can be said to be over. The days ahead promise to be exciting as legal and constitutional experts offer more explanations on the import of the judgement.