Constitutionality of the president suspending the office of the president under Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria

By Sam Kargbo

Introduction

Legal practitioners constantly grapple with complex and evolving issues that challenge the depth of our legal understanding. One such issue that has sparked intense debate is the invocation of emergency powers under Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria (as amended).

Recently, the President exercised emergency powers to suspend the Governor and the State House of Assembly of Rivers State. Earlier, the President of Nigeria used state of emergency powers to remove the Governors of Plateau State in 2004, and the Governor of Ekiti State in 2006.

In justifying its support for the suspension of the Governor of Rivers State by the President, the National Assembly referred to the recent judgment of the Supreme Court.

The recent judgment of the Supreme Court in the case of The Rivers State House of Assembly & Anor vs. The Governor of Rivers State is to the effect that the constitution or the authorities it creates can be endangered by internal unrest or brazen abuse by state functionaries. An example is the case of Rivers State, whereby the Supreme Court held that the Governor was a threat to democratic governance. Governor Siminalayi Fubara, fearing potential impeachment, allegedly took such measures as preventing the Assembly from convening, withholding its funds, and demolishing the legislative building. The Supreme Court stated that such political disagreements do not justify attacks on the Assembly, the Constitution, or the rule of law, asserting that these actions effectively dismantled the state’s governance Structure.

This raises a crucial constitutional question: Can the President suspend the Office of the President itself and assume absolute executive power as Commander-in-Chief in a national crisis?

This article critically examines whether, under extreme circumstances, the President can suspend democratic institutions, including the National Assembly and the Office of the President, and govern under martial law to restore constitutional order and national security.

State of emergency and its constitutional implications

The justification for emergency powers

Governments worldwide have long assumed extraordinary powers to manage crises, including wars, natural disasters, civil unrest, or pandemics. During a state of emergency, fundamental rights and democratic processes may be curtailed. However, the extent to which emergency powers can override constitutional principles, such as separation of powers, checks and balances, and rule of law, remains contentious.

The scope of emergency powers under Section 305

Section 305 of the Nigerian Constitution empowers the President to declare a state of emergency under specific conditions, such as war, internal unrest, natural disasters, or other threats to national stability. The provision is notably broad, granting the President wide discretion to determine the severity of a crisis and the necessary response.

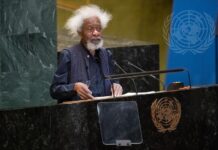

READ ALSO: Soyinka faults Tinubu’s emergency rule in Rivers, says it’s against spirit of federalism

Legal scholars such as Professor Mike Ikhariale argue that this discretion allows the President to suspend even core democratic institutions in extreme cases. Tope Ibitola, Esq. further contends that the term “extraordinary measures” in Section 305(3)(d) implies that the President may take actions outside the ordinary constitutional framework, provided they are necessary to prevent the collapse of the state. This includes the temporary suspension of certain democratic institutions.

The risks of unchecked emergency powers

The ambiguity of “extraordinary measures”

Section 305 does not define “extraordinary measures,” leaving room for expansive interpretations. This ambiguity creates the potential for abuse, as an unscrupulous President may manipulate an emergency to consolidate power. Historical precedents worldwide demonstrate how emergency powers can be exploited to erode democratic governance.

The role of the military in emergencies

A significant concern is the Constitution’s failure to specify when military intervention is appropriate. The text should explicitly limit military involvement to situations where civil authorities have demonstrably failed to maintain order, ensuring that emergency rule does not morph into prolonged military control. The six-month timeframe for emergency rule is arguably excessive, providing ample opportunity for executive overreach.

Federalism and state autonomy

Another flaw in Section 305 is its infringement on federal principles. States should have the autonomy to manage their emergencies without excessive federal intervention. The President’s power to suspend elected state governments undermines Nigeria’s federal structure.

Historical and comparative analysis

Several countries have provisions allowing the central government to assume emergency powers:

India: Under Article 356, the President can dissolve state governments in cases of constitutional breakdown.

Pakistan: The military has frequently assumed executive control during emergencies, often citing national security concerns.

By comparison, Nigeria’s constitutional framework provides substantial leeway for extraordinary measures, suggesting that under dire circumstances, the President may legally justify suspending even the highest office of the land.

Safeguards and constitutional justifications

While Section 305 does not explicitly authorize the suspension of the Office of the President, its broad emergency provisions allow for extreme measures under national crises. However, key safeguards must be maintained:

1. Legislative Oversight: The National Assembly must approve any declaration of emergency to ensure democratic legitimacy.

2. Time Limits: Emergency powers must be strictly time-bound to prevent indefinite authoritarian rule. Egypt’s decades-long emergency rule (1967-2012) serves as a cautionary tale.

3. Judicial Review: Courts must have the authority to determine the necessity and proportionality of emergency measures.

4. Public Interest Justification: Any suspension of democratic institutions must be justified solely on national security grounds.

The need for constitutional reform

As currently structured, Section 305 is a dangerously broad political weapon in the hands of the President. The provision must be amended to:

· Clearly define “extraordinary measures” to prevent overreach.

· Explicitly prohibit martial law and indefinite emergency rule.

· Restrict military involvement in civil governance during emergencies.

· Preserve state autonomy by limiting federal intervention in state crises.

Conclusion

The expansive powers granted under Section 305 suggest that, in extreme situations threatening national survival, the President may suspend even the Office of the President, centralizing authority under the Commander-in-Chief. While this remains a theoretical possibility, the historical dangers of unchecked emergency powers cannot be ignored.

Nigeria must urgently reform Section 305 to ensure that emergency provisions do not become a gateway to authoritarian rule. The delicate balance between national security and constitutional governance must be safeguarded to preserve democracy and the rule of law.

- Sam Kargbo, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), writes from Abuja, Nigeria