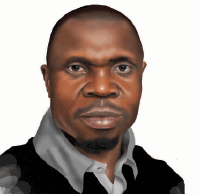

On Thursday, August 21, President Goodluck Jonathan sounded like a statesman who should be believed; except that he is a politician. It was the former German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, who once said “never believe anything in politics until it has been officially denied”.

Even clowns believe they are better than politicians when it comes to credibility. Listen to actor and director, Charlie Chaplin: “I remain just one thing and one thing only – and that is a clown. It places me on a far higher plane than any politician.” Hmmmmmm!

However, as imperfect and ‘politician’ as President Jonathan is, somehow, you may be persuaded to believe that he should sometimes be given the benefit of the doubt; for specific reasons.

During the 53rd anniversary of Nigeria’s Independence, Jonathan promised to organise a national conference. While some people dared him, others taunted him. They vowed he wouldn’t have the guts to try it, except he was crazy enough to want to preside over the disintegration of Nigeria.

Then he set the ball rolling. He picked a group of unlikely people to work out the modalities for the conference. The group did. Then he pushed on by announcing the date and who the delegates would be. Still cynics kept firing criticisms down the aisles.

On March 17, he inaugurated the conference. Two weeks later, the conference marched towards the brink when the issue of voting pattern surfaced. Jonathan turned down the invitation to intervene in the face-off, which was mainly between Northern and Southern delegates.

He stated his reason: “We had at the conference 492 delegates and six conference officials who, all in their individual rights, are qualified to lead our great country, and if they were unable to take decisions, we should be in real trouble.”

He stayed off. The matter was resolved by the delegates internally. This was just one of the many crushing issues that the conference faced and somehow managed to resolve. Five months later, with a few billions of naira spent, the conference came to a close, with a story to tell.

About 3pm on Thursday, August 21, Jonathan walked into the plenary hall of the National Judicial Institute (NJI), the same venue he had inaugurated the conference in March, to declare the convocation closed.

If his first visit was characterised by subdued optimism or near uncertainty, on this occasion, he entered the hall with a smile and a bounce in his steps. There was something triumphant about his walk and his words, and even the applause he received.

It was his way of saying: the job has been done. My hopes have been fulfilled. The cynics have been silenced. I told them we would do it. They neither believed me nor trusted you to deliver. But you beat them to it. It’s time to celebrate!

His words: “I am happy that this dialogue has gone on very well. Our moment for national rebirth is here. We have to rekindle hope not only within our country but in the entire African continent where collectively our leadership is acknowledged.”

For those who predicted disintegration of Nigeria at the turn of the new centenary, Jonathan said they needed to hide their faces in shame, as the possibilities of the new vision for Nigeria are actualised.

He spoke passionately about Nigeria: “In place of disintegration, we shall have integration. In place of bitterness and spilling of blood, we shall have sweetness and healing in our land.

“Henceforth, our country shall become like running water that approaches a rock; rather than stopping, it takes a curve and flows on.”

Then he told the delegates who applauded him with excitement: “You have done your patriotic duty; we, the elected, must now do ours. Your work is not going to be a waste of time and resources. We shall do all we can to ensure the implementation of your recommendations which have come out of consensus and not by divisions… It is my hope that with what you have done, our country is on the right path to getting the job of nation building done.”

For those who still think that the conference was a failure because it could not conclude discussion on the derivation principle, Jonathan said not agreeing on all issues only showed the sincerity of the discourse.

He said nobody was at the conference to be politically correct. People spoke passionately and argued strongly in favour of what they genuinely believed in. As a result, there were bound to be strong disagreements.

I agree with him that, “If everybody agreed on every issue, the debate would not only be lacking in quality and passion; it would also be said to have been stage-managed.”

That the national conference succeeded was purely because majority of the delegates saw Nigeria as their own “dear native land” where “though tribe and tongue may differ, in brotherhood” they stood.

So, finally, the conference has ended. The delegates have delivered. No matter the roads they took to arrive at the destination, the truth remains that they have arrived. They have conquered all odds. They have survived trials and errors.

The report is now with Jonathan. Whatever he does with it would depend on what his intentions for the convocation were. The people have spoken, the leaders must act.

Henceforth, nobody may remember how delegates arrived at decisions. History will only record what Jonathan did with the report.