Nigeria’s $2b energy transition fund: Ambition is welcome but architecture will decide impact

By Precious Ebere-Chinonso Obi

Nigeria’s announcement of a $2 billion Energy Transition and Climate Fund, alongside an ambition to unlock $25–$30 billion annually in climate finance, is not just another policy headline. It is a test of whether the country can finally convert climate ambition into bankable, inclusive, and scalable outcomes or whether we repeat a familiar cycle of bold declarations followed by limited domestic impact.

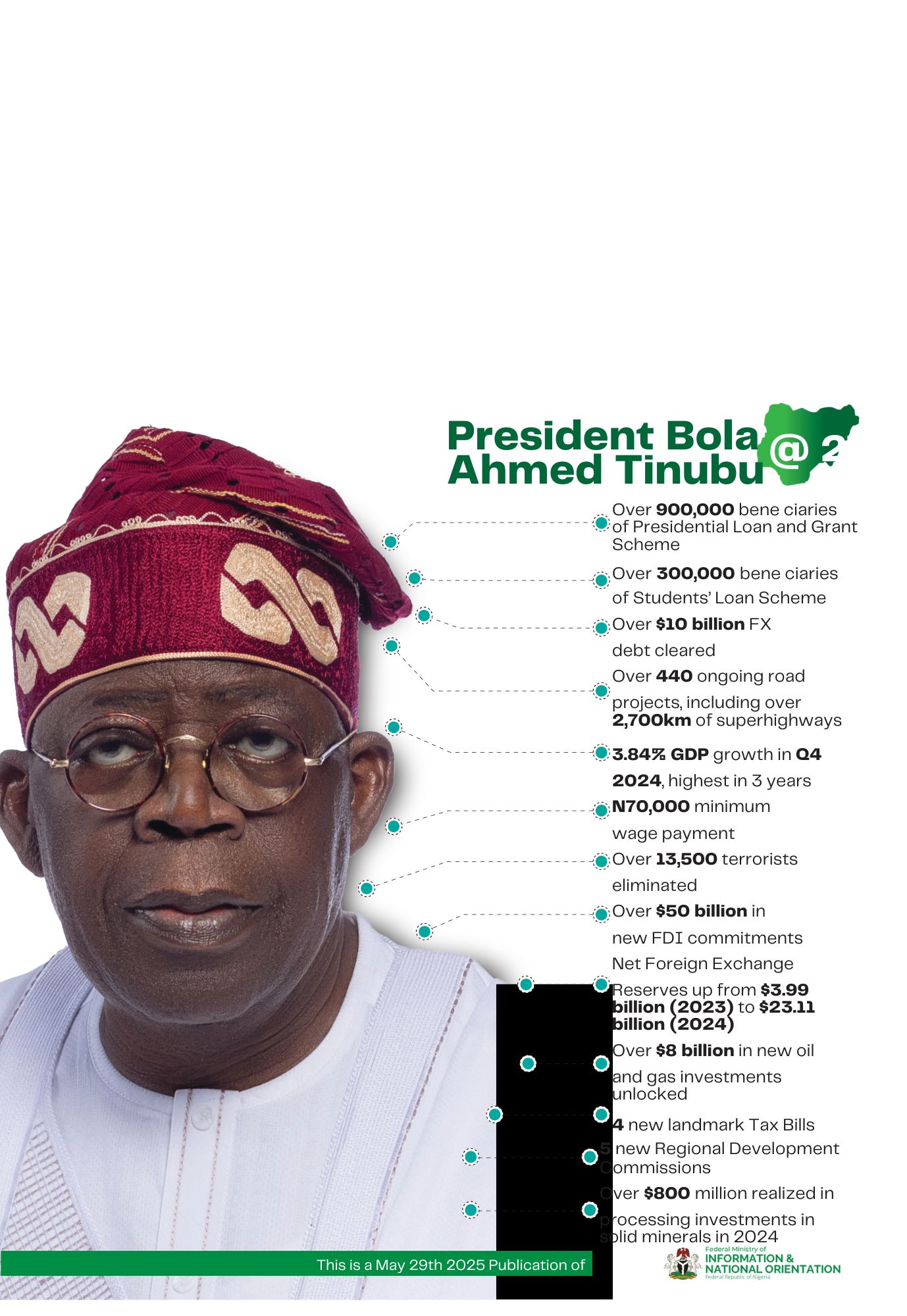

From Abu Dhabi, President Bola Tinubu framed the initiative as a signal that Nigeria is open for green business. Investors responded positively in principle, as evidenced by the oversubscription of Nigeria’s sovereign green bonds and Lagos State’s subnational green issuance. But global climate finance history tells us something important: money does not flow simply because funds are announced; it flows because systems are credible, transparent, and investable.

According to the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), Africa receives less than 3% of global climate finance annually, despite bearing a disproportionate share of climate risk. Nigeria’s challenge, therefore, is not access alone but absorption capacity.

A $2 billion fund will only matter if it addresses three long-standing bottlenecks:

Project readiness: The World Bank estimates that over 60% of climate projects in developing countries fail to reach financial close due to weak feasibility, governance gaps, or unclear revenue models.

Currency and policy risk: International investors remain wary of FX volatility and regulatory inconsistency, issues consistently flagged by institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB).

Local participation: Climate finance in Africa too often bypasses local developers, SMEs, and women-led enterprises, concentrating capital in a few large players.

If Nigeria’s Climate Investment Platform becomes merely a high-level pooling mechanism without solving these structural issues, it will struggle to deliver transformational outcomes.

Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan (ETP) rightly targets net-zero emissions by 2060, but the country also has over 85 million people without access to electricity, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). This dual reality demands a different framing: energy transition in Nigeria must first be an access transition. This is why the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority’s $500 million Distributed Renewable Energy (DRE) Fund is one of the most important signals in this announcement. Decentralised solar, mini-grids, and clean cooking solutions consistently deliver the highest development returns per dollar invested, as documented by Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL).

However, scale will only come if new funds deliberately crowd in: Local financial institutions, State governments with bankable subnational energy plans, Community-based and women-led energy enterprises

Without this, Nigeria risks building a transition that looks impressive on paper but remains invisible to households and small businesses.

Nigeria’s green bond success is encouraging, but it also raises a governance imperative. The OECD has repeatedly warned that weak monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks undermine investor confidence in emerging-market green finance.

For the new Climate and Green Industrialisation Investment Playbook to work, it must go beyond investor roadshows and answer hard questions: How will project impacts be independently verified? What safeguards exist to prevent political capture of climate funds? How are states and local governments integrated into the pipeline?

These questions matter because climate finance is increasingly performance-based. Institutions like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and major private climate investors now tie disbursements to measurable outcomes, emissions reduced, jobs created, and energy connections delivered.

The President’s emphasis on grid modernisation, AI-enabled efficiency, and electric mobility reflects global best practice. Yet technology adoption without regulatory clarity often stalls.

India’s renewable energy success, for example, was driven less by technology breakthroughs and more by predictable tariffs, long-term power purchase agreements, and clear industrial policy lessons Nigeria can adapt.

Nigeria’s climate moment is real. Global capital is actively searching for credible emerging-market transitions, and Africa’s green industrialisation potential is now widely acknowledged by institutions such as the World Economic Forum.

But ambition must now shift from announcements to architecture. The $2 billion fund should be judged not by how much it raises, but by: How many Nigerians gain reliable energy access, How many local enterprises become climate-bankable, How transparently funds are deployed and tracked.

If Nigeria gets this right, it will not just transition its energy system, it will redefine how African countries lead in a climate-constrained world. If it gets it wrong, this will be remembered as another well-funded idea that never fully touched the ground.

The difference lies in the details and the discipline to execute them.

- Precious Ebere-Chinonso Obi is the CEO of Do Take Action and independent consultant on edtech, climate change, public policy, and women’s procurement empowerment.

.