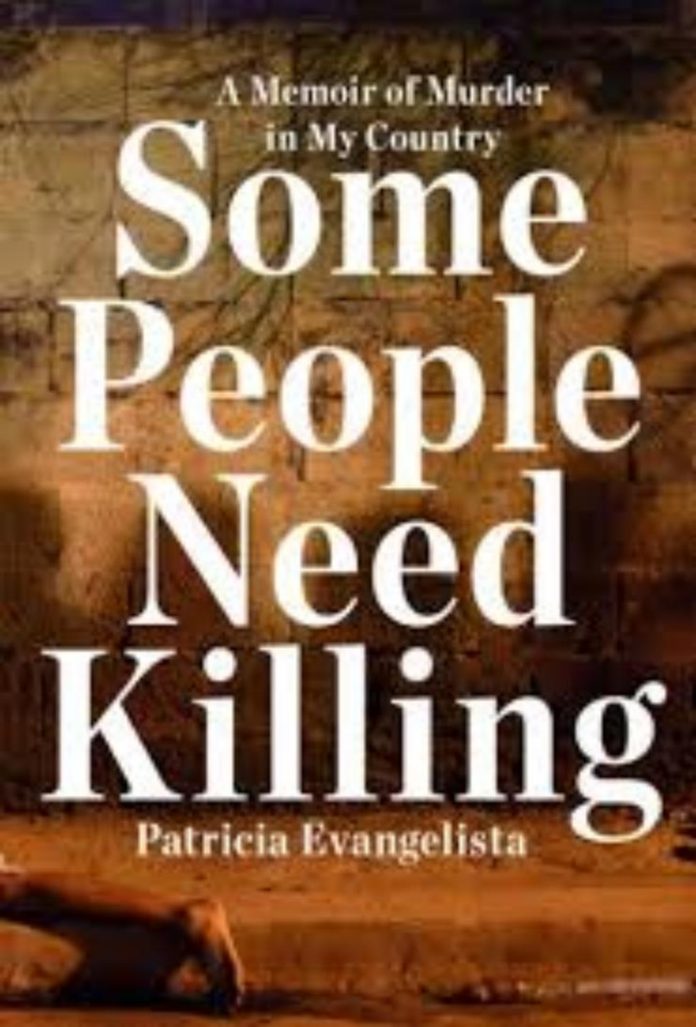

The head of state needs examining: Patricia Evangelista’s brave, enthralling, and chilling book, Some People Need Killing, chronicles the spree of killings that followed the election of Rodrigo Duterte to the presidency of the Philippines. Her story could very well have become like the map in the Borges story which is exactly the size of the country it represents.

By Missang Oyongha

The killings began immediately. On the first day of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency in June 2016, a Chinese man was found shot to death in Tondo, a Manila slum. Project Double Barrel had started. Its objective, coldly and euphemistically stated, was “the neutralization of illegal drug personalities nationwide”. The newspaper that Filipino journalist Patricia Evangelista worked for, Rappler, had published a prescient editorial on May 2, 2016: “If Rodrigo Duterte wins, his dictatorship will not be thrust upon us. It will be one we will have chosen for ourselves…We write this as a warning.” In typical Trumpian fashion, Duterte would later dismiss Rappler as “fake news.” Jason Quizon, a Filipino expat and ostensible liberal, had rationalised Duterte’s bloodthirsty campaign rhetoric as “fodder for the gullible masses”, and admired the candidate for being “a man of action”. By January 2017 there were 7,080 extrajudicial killings related to Operation Double Barrel, and Duterte’s war on drugs and the rule of law was entering another phase.

Patricia Evangelista’s brave, enthralling, and chilling book, Some People Need Killing, chronicles the spree of killings that followed the election of Rodrigo Duterte to the presidency of the Philippines. Her story could very well have become like the map in the Borges story which is exactly the size of the country it represents. The Philippines, South Asia’s oldest democracy, has also been one of its most benighted, enduring American colonialism, Japanese occupation during World War 2, and the horrifying dictatorships of Ferdinand Marcos Snr. and Rodrigo Duterte. During the Cold War presidency of Marcos Snr., the country’s putative anti-communism licensed all kinds of bloodshed and earned the support of the Reagan White House. Evangelista’s tone is by turns elegiac, bracing, ironic, forensic, and indignant. Her book, traumatic as it is to read, demands to be read, just as it demanded to be written. Even an account as scrupulous and detailed as this must acknowledge its inadequacy before the enormity of the carnage: “Numbers cannot describe the human cost of this war, or adequately measure what happens when individual liberty gives way to state brutality. Even the highest estimate – over 30,000 dead – is likely insufficient to the task.”

“A lot of them are no longer viable as human beings”, declared Duterte of drug addicts, and with that one sentence made himself judge, juror, and vicarious executioner. One member of the vigilante Confederate Sentinel Group (CSG) told Evangelista: “I’m not really a bad guy. I’m not all bad. Some people need killing.” The CSG was repeatedly named as one of the armed groups licensed by the Duterte regime to “neutralize” drug suspects. There was a grim semantic battle over whether to neutralise meant, as the Duterte regime insisted, merely “to overcome resistance”, or whether it actually meant the extrajudicial murder of thousands of alleged drug suspects who had offered no resistance whatsoever. The mayors of several Filipino cities, accused of involvement in the drug trade, were “neutralised” as well. Brimming with indignation and hyperbole, Duterte claimed that drug addicts and dealers had killed 77,000 Filipinos in the three-year period leading up to his presidency. Evangelista considers this tally wildly arbitrary and unlikely.

The killings began, actually, in Davao City, long before Rodrigo Duterte acceded to the presidency. Davao City, where Duterte served as mayor for twenty-two years, had long been notorious for the extrajudicial killings of drug addicts and dealers, and it is obvious now that the abuses of Duterte’s mayoral period served as a dress rehearsal for Project Double Barrel during the Duterte presidency. In 2009 Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a 107-page report on extrajudicial killings in Mindanao. Its title, You Can Die Any Time”, was a quote from Mayor Rodrigo Duterte himself. It was typical of the sort of language that had become a trademark of the politician. The summary section of the HRW report carried an epigraph also quoting Duterte: “If you are doing an illegal activity in my city, if you are a criminal or part of a syndicate that preys on the innocent people of the city, for as long as I am the mayor, you are a legitimate target of assasination.” The HRW report listed Duterte’s nicknames: The Punisher. The Enforcer. Dirty Harry.

The victims were “drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children”, hundreds of whom had been killed in Davao City and elsewhere in Mindanao. Others who were killed were “victims of mistaken identity, innocent bystanders, and the relatives and friends of the intended target”. Some of the victims were themselves former hitmen for the notorious DDS, the Davao Death Squad, eliminated presumably because they knew too much. One hitman was reportedly paid for his services, repeatedly, with a cheque signed by Mayor Rodrigo Duterte himself, a brazen paper trail. To prove his unquestioning loyalty to Duterte and the Davao Death Squad, one former member, Sergeant Arturo Lascanas, even had his own two brothers Cecilio and Fernando killed for being alleged drug dealers.

Duterte was a product and symptom of the dynastic nature of Filipino presidential politics. His father had been a provincial governor under Marcos Snr. His own daughter, Sara Duterte, succeeded him as Davao City mayor. As Evangelista writes in a deadpan tone, “Duterte the First begat Duterte the Second. Aquino the Second begat Aquino the Third. Marcos the First begat Marcos the Second begat Marcos the Third, presidents begetting presidents begetting vice-presidents…” The irony of course is that Duterte’s extradition to The Hague was not the result of President Marcos’ commitment to securing justice for Duterte’s victims, but of an internecine strife between the Marcos and Duterte factions of the Filipino presidency.

Frantz Fanon told Simone de Beauvoir in 1961 that “all political leaders should be psychiatrists as well”, but given the evidence of Rodrigo Duterte it can be argued that all political leaders should be psychologically evaluated all the time, and especially in advance of office. What can we surmise about the mental makeup of a man who mused, about a nun who was murdered and raped, that “the Mayor should have been first?” First to indulge in necrophilia, that is. What are we to make of a man who described himself by turns as “a small-town boy”, “an ordinary Filipino”, and “just an ordinary killer?” Evangelista rehearses this paradox when she explores the idea of Duterte “[holding] the high ground while glorying in mass graves; [professing] vulgarity while promising morality; to [denouncing] laws while pledging to uphold them; [believing] in the likelihood of one murder while denying the possibility of all others; [claiming] to be a killer while repudiating killers – this was the magical reality of Rodrigo Duterte.” What are we to make of a Filipino society in which, as the HRW report from 2009 noted, “These killings have not been unpopular.”

Evangelista took immeasurable risks to investigate the stories she recounts here. She visited families whose members had been victims of extrajudicial murder; she went to funerals; she went with other journalists to photograph and document the late-night scenes where drug suspects had been murdered in cold blood; she secretly interviewed former death squad members. At one point she cultivated, or was cultivated by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Domingo, an urbane police officer. Despite his performative indignation, it is at Domingo’s Manila police station that the Commission on Human Rights finds a secret cell hidden behind a bookshelf. Even when nine detainees stagger out of the cramped enclosure, Domingo swears that he had no knowledge of the secret cell, or of the detainees. “Do you consider me a friend, Pat”, Domingo asks Evangelista. “Trish, you believe me, don’t you?”

Evangelista’s book is full of poignant stories, but perhaps the most moving is that of Clarita Alia, whose four teenage sons were extrajudicially murdered in Davao City between 2001 and 2007. The HRW report also covered the Alia family tragedy. A police officer had threatened Clarita that her sons would be killed one after the other, because she had prevented the warrantless arrest of her eldest son, Richard. Richard Alia was 18 when he was stabbed to death in July 2001. Christopher Alia was 17 when he was killed in October 2001. Bobby Alia was 14 when he was killed in November 2003. Fernando Alia was 15 when he, the last of his brothers, was killed in April 2007. No legal or moral or political rationale can excuse these murders, or the thousands of murders that came before and after. The question raised by this chronicle of bloodshed is why in 2016 Filipino voters decided that the reins of the presidency should be handed over to a man who had shown nothing but disdain for the rule of law, and for human life. Jason Quizon eventually arrived at a state of voter’s remorse, horrified by the unending photos and videos of victims whose guilt had been decided by whim, not by law.

- Missang Oyongha was on the staff of the Presidential Advisory Committee on National Dialogue, and currently serves as the Editor of MMG. He can be reached via email: missang.oyongha@gmail.com