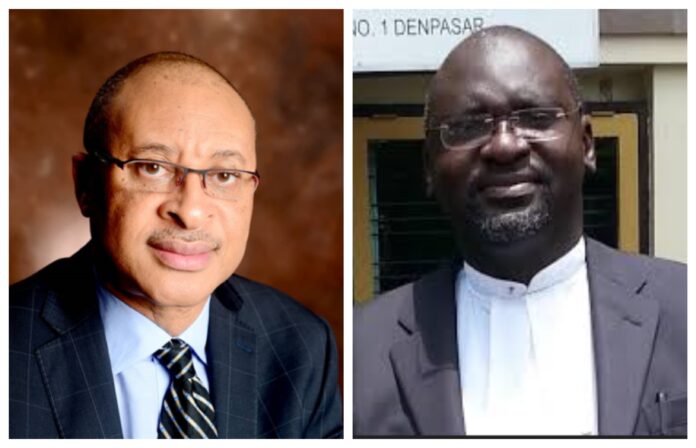

Ogebe and Utomi question US election, lament emergence “Trump dictator democrat like Buhari”

By Jeph Ajobaju, Chief Copy Editor

Pat Utomi, a political economy professor in Nigeria, and human rights lawyer Emmanuel Ogebe, based in the United States, have joined their voices to critics of American democracy which reelected Donald Trump as US President on November 5 and examined its impact on democracy across the African continent.

They bared their minds during an interactive session at the President Wilson Center Think Tank in Washington titled “Trendlines and Transformations in African Democratic Governance Lessons for US-Africa”, where Ogebe lamented that America is becoming like Africa where coupists are elected back into power.

Both Ogebe and Utomi were responding to US Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy Dahna Rand who asked for suggestions from the dialogue for improved US-Africa engagement.

Below is the transcript of the session as Ogebe forwarded it to TheNiche:

Oge Onubogu

Thank you very much, Charles. So I promised that I wanted to keep this interactive, so I want to go turn to the audience now to see if there are any questions. I can take one or two questions now before I turn back to our panelists with a few questions. So we have two questions here. Please introduce yourself and keep it to a question.

Let’s start with Dr. Utomi over here. There’s a microphone.

Utomi

Um, my, my, my name is Patrick Utomi, I’m a fellow here at the Wilson Center. I am curious about something that, uh, Peter Lewis and I had a session on, um, the Afrobarometer just in the early days at the Lagos Business School and the affect that people felt for democracy and all of that.

It wasn’t stomach infrastructure pushing it clearly back in those days where people wanted democracy. Now we see, James Robinson in his remarks after they were awarded the Nobel Prize two or three weeks ago, makes a point that development is an intensely political process.

It seems to me that most people are feeling that they cannot have their desires for a better life represented in the political system, and therefore, are turning more to a sense. Thanks for watching.

If democracy can’t help us live well, what’s the point of it? I wonder what sense you get for this as we look at, uh, reactions to democracy in today’s world. Thank you, Dr. Utomi, and the gentleman behind him.

Ogebe

Yes, my name is Emmanuel Ogebe with the U. S. Nigeria Law Group. I think that we actually should reframe the question, which is, what are the trend lines of democracy in America?

Uh, showing to Africa, uh, if we look at the recent election, it really mirrors what has happened in Africa. We see a situation where someone who tried to overthrow a government is being elected as President of America. That’s what Buhari did. He tried to overthrow a government successfully, and he came back as head of state.

The only difference, of course, is that Buhari ruled as a dictator and came back as a Democrat and Trump ruled as a Democrat and is coming back as a dictator. And so I would say that America, uh, for some reason is trending in the wrong direction and it may be misdirecting Africa. I should end my thoughts with one quick, uh, comment about the stomach infrastructure.

We talked about African electorate being susceptible to economic, uh, necessities. And if you look at the expressions of the electorate in America, it was the same thing. Stomach infrastructure. They believed false economic indicators, and that was the reason why they claimed they voted the way they did.

So at the end of the day, I think America is becoming a failing democracy, and it is sending a wrong signal to Africa. Thank you.

Onubogu

Thank you very much. So with those two questions about development being a deeply political process or development being seen as a political process and what are the trend lines in the U.S. and elsewhere showing, uh, the continent. Peter, what one those questions was directed to you, sir?

Peter Lewis

Well, on the, uh, you know, referring to the to the Afro barometer, uh, issue.The definition of democracy, we, you know, Afrobarometer has asked people, uh, what does democracy mean to you? It’s an open ended question.

It’s not set, you know, sort of, uh, uh, multiple choice, uh, question. And some people, say in South Africa, clearly express a kind of human, human, uh, communitarian and social democratic understanding of democracy.

Democracy is equality. Democracy is poverty reduction. Democracy is prosperity for all. Those are the kinds of answers you get.

And you get that sometime, you know, uh, in, uh, some, uh, West African countries and, and other, uh, uh, places as well. And then many countries, uh, in many countries across the continent, you get answers that, uh, comport with a kind of standard liberal democratic definition of democracy.

They say it’s free and fair elections, it’s freedom of speech or freedom of assembly, it’s multiple parties, it’s, it’s an open political, uh, uh, sphere.

And, you know, these are not educated urban residents that are only being surveyed. They’re also farmers and people who live in, uh, the hinterland and so forth. So these are the answers that they come out with.

Now, so what it suggests in line with Pat’s question is there are intrinsically political elements to the process of political change that people are looking to.

Am I able to express a voice through elections? Do we get any accountability of leadership? Whether it’s MPs between elections listening to me or policy initiatives from the parties or from the government that address inflation or food shortages, or health emergencies, or any number of other questions, or are we looking at a distant, transactional political class that really is not interested in our concerns, or in our interests, our fundamental welfare, and it’s just sort of, you know, feeding from the trough, and doing deals amongst themselves.

That can give rise to, anti democratic sentiments, it can give rise to violent mobilization as it has in Nigeria, where, uh, we’ve seen a surge in violence across the country, over the last 25 years, and, so we can get different kinds of responses from that.

I’ll stop there.

Onubogu

Does anyone want to touch on the question on what the trend lines in the U. S. and elsewhere are showing to the continent? Charles?

Charles Ukeje (OAU Ife)

Thank you very much. It’s something I was pondering as I was preparing to come here. I feel that one of the things I hear people talk about is, if you cannot help me, don’t complicate my problem.

I hear people on the continent say, for instance, that, look, established democracies themselves are in tumour, from Europe to North America. And so how, because of the kind of challenges that they face within, the commitment that we used to see in terms of democracy promotion is no longer there.

And that raises a very important question about, you know, as long as established democracies are themselves at the crossroads, to what extent should we expect that, you know, they would be able to add value to any process of democracy.

Another point is really that, we are seeing things happening in established democracies that some of them cannot or may not even happen on the [African] continent, as bad as the reality on the continent is.

I mean, look at Europe today, from the UK to France to The Netherlands, you know, it’s been, an upsurge in far right political parties and ideologies. It’s been, you know, xenophobia against others. It’s been antiSemitism, and all of these.

And these are countries that have been, very significant contributors, including the U.S. actually, to democracy promotion on the continent. So there’s a whole lot of worry. There’s a whole lot of worry about established democracies today, especially if they have to make a choice between stability and democracy. We choose stability on the continent because stability helps to promote market, okay?

Nobody wants to invest, nobody wants to foray into a space where there is instability. So if you have stability, it doesn’t matter what kind of stability. It doesn’t have to be stability, you know, a democracy-induced stability. So if democracy is going to be tumultuous on the continent, but you can have stability of different forms, then why not?

So there’s today, that concern, and I hear it from colleagues, I hear it from people in government that, look, after all, you guys are not better than us. And for me, this is one major negative vibe that is coming from established democracies about the prospects for the continent.

If you can’t deliver on elections, something as basic as elections, on what basis are you going to expect African countries that are struggling with so many different things to be able to deliver on elections and in a way that emboldens the political elite in many African countries to just basically act in ways that can promote impunity and undermine democracy.

Onubogu

Did you want to add something, Rubia?

Tawfik

Yeah, I think on the two points very quickly. I think we sometimes do not put these debates in historical perspective and kind of forget that we have been there before.

I mean, in the 1950s and 60s, this was the narrative, right? That well, Africa cannot actually afford pluralism and democracy and thus let’s tackle development first. And the experience of the four decades from the 50s until the end of the 80s indicated that this did not happen.

And even more recently, the coups that justified the military overthrow of a democratically elected president because he is not able to deliver on stability, we have seen in the last two, three years that they are not able also to deliver the mission of stability.

And even in North Africa, we have this kind of social pact that, well, we’re going to offer you subsidies and employment and so on in exchange for the loyalty to the regime. Again, this did not deliver.

So, I think we should not repeat the same mistake of assuming that having more authoritarian regime will actually deliver on democracy. And then, secondly, I think we have reason to be pessimistic about the prospects of established democracies and how they’re impacting our own experiences.

But what I can see also is that in established democracy, there is a strong society that is actually pushing back and using the available public space. I mean, in our countries, the public space is not even available.

Yes, as Latif has said, we have the parallel kind of virtual public space that we’re actually inventing. But this cannot make up for the real struggles that are gonna change things on the ground.

So let me pick up on that question and turn to you, Latifa, on these new spaces that are being created. Technology, as you pointed out in your remarks, it’s basically changing the landscape for political communication.

We are seeing new voices engaged in the process. I think Jima Bouadi from CDD Ghana describes youth on the continent as this new democratic group, anti authoritarian movement that are creating space for themselves through social media and using technology to make their voices heard in the process.

Now, you mentioned disinformation and hate speech that might emanate from social media spaces. But then again, we also see the good side of this on freedom if it creates that space for freedom of expression for people to engage and to participate.

So, I’m wondering with this question and this challenge that we see on the continent on what sort of space for the effective use of technology of creating this space for voices to be heard.

__________________________________________________________________

Related articles:

Ogebe decries ‘Trump capture’ of American nation and justice system after 4-year battle

Utomi raises alarm exchange rate heading to N10,000 per dollar

Ogebe states Trump’s case against Trump (part 1 – debunking immigration myths and misinformation)

First anniversary of Tinubu’s state capture showcases wasteful wandering in the wilderness

__________________________________________________________________