Situation one. Since the late 1980s, most students who passed History in their West African Examination Council (WAEC) tests did so of personal effort. That was when Nigeria started the move to remove History from its school curriculum. Official reasons Nigeria advanced for expunging History as a course of study were that “students are shunning it”. The country also claimed the decision was necessitated by the fact that there were few jobs for History graduates, coupled with the dearth of teachers.

However, critics have said that Nigeria’s abhorrence of history is not new. There is no official account of the Civil War, reported the Vanguard newspaper. “When we obliterate history, we should also destroy our artefacts, burn our museums and monuments, heritage sites and archaeological activities. A generation of Nigerians without knowledge of history would not appreciate these treasures,” the paper captured in an editorial.

Situation two. Man, in the Hobbesian state of nature, is promiscuous. When you narrow it to Nigeria, some ethnic groups, take it or leave it, are seen as more vulnerable than others. With all sense of modesty, the Yoruba of the present South West are one of those that are more ‘liberal’ in matters of sexuality. Many believe that while an average Igbo family sees pre-marital pregnancy as taboo, the average Yoruba family is said to be indifferent.

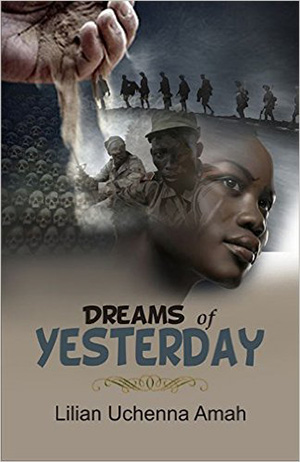

The two situations above are issues seen as sacred in our Nigerian society. But banker-turned-Nollywood actor and producer, Lilian Amah-Aluko, hazards to crack them in her new novel, Dreams of Yesterday.

TheCivil War took Lekan, a Yoruba soldier fighting for Nigeria, to Igboland where she met Nnena, a pretty virgin who is orphaned by the pogrom in the North. She is taken to Benin City, Bendel State, with other women who Lekan’s men spared during a raid. Compassion turns to love, and… ‘illegal’ inter-tribal marriage which produces a boy, Nonso. To avoid further victimisation of Nnena, Lekan sends her to Sierra Leone where she stays …and graduates while the war lasts.

By happenstance, Lekan falls in love with another Igbo woman, Ndidi. When the Yoruba soldier re-unites with his family, letting Ndidi go becomes an issue. So, Nnena commits suicide… to let the two ‘lovers’ be. But the gods are wiser. For them, “You cannot have your cake and eat it.” So, Lekan cannot have Ndidi either.

Is it Nnena that caused the accident that took the life of the ‘interloper’? Amah-Aluko seems to agree with the fact that the dead always fight for what is theirs.

Dreams of Yesterday tries to paint Lekan as a gentleman. But he ends up being unfaithful to his wife, bringing out the ‘liberal’ nature of the Yoruba. Granted, he started making love to Ndidi when he was experiencing memory loss, but what happened when he ‘came back’?

This review is just a perspective, but those who have associated with the Yoruba would testify that a Yoruba girl who gives birth out of wedlock is celebrated as much as the one in her husband’s home.

Another issue the book throws up is that no matter how much you try to asphyxiate history, it will never die. Nigeria’s story will be incomplete without the Civil War. So, trying to shield the atrocities of the war from coming generations will always come to naught because aside the teaching of history in schools, books like Half of a Yellow Sun, There was a Country and Dreams of Yesterday will always come up to say the ‘truth’ as the authors know it.

Lekan’s loss of the two women he claims to love smacks of the long hand of nemesis. He is punished for hurting the woman who loved him dearly. And Ndidi’s death can be mirrored in the same manner – she was sleeping with another woman’s husband.

The style of writing Dreams of Yesterday is very simple that even mature children can read and understand.

However, it is written, like most English novels, in open plot, also known as open-end plot. For instance, what became of the remains of Ndidi’s parents who were slaughtered in Kano is not in the story. Did Lekan start anything emotional with Ralu, who has grown into a lady at Nnena’s demise? There are other questions the book throws up but does not answer.

Although Amah uses history to gain leverage through language and plot, she is not a crusader fighting on one end of the divide. If anything, she focuses on the ordinary lives destroyed, the lives thrown into trauma beyond the trenches and away from the background and those who carry the scars of war in their hearts.

The story cuts onions in your face. If and only if you have run out of tears, you sure will drop some before you drop the book.

Well-written, the book still could not escape the printer’s devil. ‘Waist’ was written as ‘wasit’ (p14), ‘superstitious’ as ‘superstitions’ (p93) and ‘mahogany’ as ‘maghogany’ (p158). Also, though the book was written in British English (BrE), some North American English (NAmE) spellings slipped in. For example, a word like ‘sceptically’ appeared as ‘skeptically’ in the book. This is pardonable because both are correct English words meaning the same thing.

Aside these few slips, the 36-chapter, 208-page book with word count of about 50,000 is an excellent production with quality paper and unbeatable finishing.

A glossary in the last pages of the book contains 54 Igbo and Yoruba expressions used in the book, for the benefit of those who are not familiar with any of the two languages.

• Anoruo is a journalist and book publisher